Almost 75 years since their first appearance, Tove Jansson’s Moominvalley books remain hugely popular with children and adults alike. And Moominpappa – memoir writer, former adventurer and lover of fine old whisky – is one of the series’ most loved characters. Richard Woodard reports.

In 1945, a children’s book was published in Finland and Sweden. The Moomins and the Great Flood, written and illustrated by a Finnish woman in her mid-20s called Tove Jansson, attracted little attention and sold few copies.

Over the next three years, two more Moomin books came out. Comet in Moominland and Finn Family Moomintroll caused a local stir; but, by the time the series drew to a close in 1970 with the publication of Moominvalley in November, Tove Jansson’s stories and characters had become a global phenomenon.

With their idyllic Moominvalley home, the Moomins – nominally trolls but, with their rounded, white appearance and large snouts, more reminiscent of friendly hippos – form the heart of the stories, supplemented by a broader cast of quirky characters, including Snufkin, Little My, Snorkmaiden and Too-ticky.

If Moomintroll is the ‘hero’ of the tales – Jansson described him as her alter-ego – his parents, Moominmamma and Moominpappa, are vital figures with their own distinctive characteristics.

As the family and friends deal with a series of natural and supernatural threats – comets, volcanoes, floods and the chilling, spectral presence of the Groke – Moominpappa is usually peripheral to the main action, often shut away in his room to write memoirs recalling his adventurous youth.

With his top hat, stick, pipe and fishing rod, he has a tendency to be stern and pompous, with a keen sense of his own importance and abilities, matched by a conviction that nobody quite understands him. And he loves whisky.

Family ties: Tove Jansson drew on her father’s life when creating Moominpappa’s character

In Moominvalley in November, we’re told that Moominpappa’s room features ‘a piece of board saying Haig’s Whisky hung over the bed’ – but his favourite whisky is Old Smuggler.

It’s not clear whether Jansson was aware of the real Old Smuggler whisky brand – a blend associated with Glen Grant and now owned by the Italian drinks group Campari – but, in 2014 and to mark the centenary of Jansson’s birth, Swedish whisky producer Mackmyra created its own version of Old Smuggler; 300 bottles made to order, but never released for general sale.

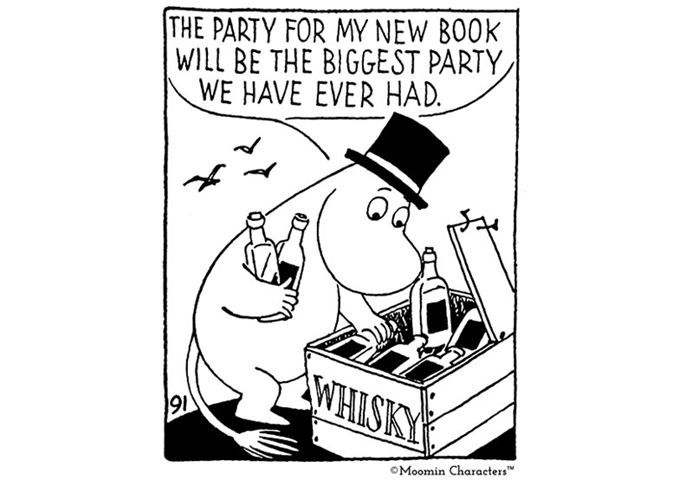

The presence of whisky is stronger in the comic strips than in the books themselves. In Moomin and the Sea – a gentler, comic strip precursor of the altogether darker Moominpappa at Sea – a crate of Old Smuggler whisky is washed up on the island.

Moominpappa gleefully grabs it for the launch party for the great novel about the sea which he has been writing, only for the sea to take back all but one bottle – which is promptly confiscated by an angry lighthouse inspector.

While Moominpappa joins in many of the family’s adventures in the Moomin books, he often cuts a frustrated figure, wistfully yearning for the excitement of the youthful adventures recalled in his perennially unfinished memoirs, some of which form the fourth Moomin book, The Exploits of Moominpappa.

This sense of ennui is merely hinted at in the early books, but comes into sharper focus in one of the short stories in the Tales from Moominvalley collection. The Secret of the Hattifatteners recalls Moominpappa’s voyage with the mysterious Hattifatteners – nondescript white creatures who are ceaselessly nomadic. It begins:

‘Once upon a time, rather long ago, it so happened that Moominpappa went away from home without the least explanation and without even himself understanding why he had to go.’

Salvage operation: In Moomin and the Sea, a crate of Old Smuggler whisky is found

Like the best folk tales, the Moomin stories hint at darker themes in their exploration of the supernatural and the cataclysmic, and Moominpappa’s angst gives this theme a psychological dimension – which finds full expression in Moominpappa at Sea.

Arguably Jansson’s finest work, this (the penultimate Moomin book) bridges child and adult fiction, placing the familiar figures of Moomintroll, his parents and Little My in a scenario brim-full of symbolism, the uncanny and the grotesque.

At the opening of the book, Moominpappa is wandering aimlessly, ‘at a loss’, and it’s quickly clear that he has reached the full pitch of existential crisis, imagining a conflagration that engulfs Moominvalley:

‘Blinding columns of flame flung upwards against the night sky! Waves of fire, rushing down the sides of the valley and on towards the sea…

“Sizzling, they throw themselves into the sea,” finished Moominpappa with gloomy satisfaction. “Everything is black, everything has been burned up.”’

In an effort to build a protective function for himself around his wife and family, Moominpappa more or less forces them to leave the comforts of Moominvalley and accompany him on a voyage to an island at the edge of civilisation, where he is to become the lighthouse keeper.

Once on the island, the sense of psychological terror builds: notches in a table marking endless weeks of solitude, an oil lamp smashed against a wall, the mass murder of red ants by Little My, dozens of dead birds buried in marked graves, fishing nets that catch only seaweed; and, prior to their arrival, no sign of a ship for four years.

Lighter touch: The comic strip Moomin and the Sea is less dark than Moominpappa at Sea

The lighthouse is a potent symbol: positioned at the boundary between land and sea, safety and danger, life and death, it is also the embodiment of Moominpappa’s attempt to regain his lost manhood – and the fact that he can’t light it is hardly encouraging.

Moominpappa at Sea also disrupts the comfortable extended family dynamic of the preceding books, distilling it down to the nuclear gathering of father, mother and son, with the correcting counterpoint of Little My, who acts like a knowing Greek chorus, commenting on the action from the outside.

Each of the other three becomes increasingly isolated, discontented and misunderstood: Moominmamma stripped of her traditional domestic function, Moomintroll undergoing a rite of passage that sees him contemplate love (of two fantastical seahorses) and death (the dread threat of the Groke).

After unsuccessfully trying to use science to explain the unpredictable nature of a sea that seems to be alive and breathing, Moominpappa takes out his anger on it in an obsessive bout of fishing. It all looks set to end in rather grim fashion – until whisky comes to the rescue.

Moominpappa has already dreamt of contraband whisky being swept into the island’s saltwater lake early in the book; now, when a storm engulfs the island, he and Moomintroll rescue the mysterious fisherman who is its only other inhabitant – and salvage a crate of whisky in the process.

Turning point: Whisky helps bring Moominpappa’s existential crisis to a close

This provides the fulcrum of the story: for the first time, Moominmamma now refers to the lighthouse as ‘home’, while Moominpappa learns to accept the irrational sea as it is, and to love it. There is laughter; the fisherman turns out to be the real lighthouse keeper (and relights the lamp). Order is restored.

Children’s fiction and folk tales often explore adult psychological themes, but there is also an autobiographical strand to the portrait of Moominpappa, recalling Tove Jansson’s bohemian sculptor father, Viktor Jansson.

A rebel and iconoclast known for his days-long parties with his artist friends, Jansson fought on the anti-Bolshevik side in the Finnish Civil War in 1918. His frequent letters home were ‘clear and sharp with life’, according to Tove Jansson’s biographer Boel Westin (incidentally prefacing the writing of his daughter and of Moominpappa), but war changed him:

‘The Viktor who returned from the front was reserved and gloomy, a quite different man who hardly ever laughed.’

Meanwhile, in Sculptor’s Daughter, her childhood memoir, Tove Jansson describes her father’s fear of Christmas candles starting a fire in a manner that recalls the imagined conflagration at the beginning of Moominpappa at Sea; and how he would calm his nerves with frequent ‘snorters’ of whisky during the festive season.

Like all the finest ‘children’s’ fiction, the Moomin books are appreciated and enjoyed primarily for what they are – damn good stories – but they also have a depth and resonance that is all too easily underestimated. And whisky plays a small but vital role in that broader picture.