Despite centuries of warfare, taxation and changing economic tides, Islay’s resilient population has kept whisky making alive on the island. Iain Russell explores Islay’s tempestuous whisky history, and the island’s recent peaty revival.

No one knows when the people of Islay – the Ileachs – began distilling, but commentators were noting the islanders’ fondness for whisky by the 1770s. It was at this time that Islay’s largest landowner, Walter Campbell of Shawfield, was actively encouraging diversification of the island’s predominantly agricultural economy through the development of industries such as linen-making, mining and fishing. Campbell hoped distilling would boost demand for locally-grown barley, earn much-needed cash for his tenants through exports, and foster jobs in new and prosperous industrial communities.

Campbell ‘farmed’ the excise duties on Islay – he held the right to set and collect the payments on the island, in return for an annual payment to the government. However, when a national prohibition on distilling was introduced in 1795 during a period of crop failures, he did his patriotic duty: he confiscated and locked away at least 90 stills belonging to his tenants, to ensure they could not be used. In addition, he gave up the excise farm; in future, the islanders would have to pay duties set by the government.

In response, according to the report of a senior excise official in 1799, Campbell’s tenants ‘got over from Ireland tinkers, who fitted up for them cauldrons and boilers as stills’. When the prohibition on distilling ended, not a single Islay distiller applied to the Scottish Excise Board for a licence nor paid a single penny in duty – the industry had gone underground.

Strong workforce: Ardbeg’s excisemen and distillery workers pictured in the 1850s (Photo: The Museum of Islay Life)

There was an explosion of whisky-related criminality on Islay during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. British historian Alfred Barnard wrote that ‘smuggling was the chief employment of the crofters and fishermen, more especially during the winter… and large families were supported by it’.

Islay whisky flowed freely to Argyllshire, Inverness-shire, Mull, Lewis, Galloway and Ireland. It was smuggled across the Mull of Kintyre to Ayrshire. It was carried in the holds of small boats along the River Clyde, hidden under cargoes of potatoes, straight to the heart of Glasgow.

At first, the small band of excisemen stationed on the island was overwhelmed by the scale of the challenge. They complained of threats and physical assaults when they attempted to confiscate or destroy the illicit stills. They called for reinforcements.

Excise boats were sent to patrol the seas around Islay, and they landed armed raiding parties to search for and destroy stills hidden in houses and byres, in bothies and in caves. Hundreds of men and women were charged each year either with making or selling whisky without a licence, most notably on the Oa peninsula and along the south coast.

Yet the Ileachs were not passive victims of excise persecution, as they are sometimes portrayed. Many offenders simply refused to turn up in court when summonsed. Members of the McEachern family, for example, were charged with breaking into an exciseman’s cellar and stealing 125 gallons of whisky. Like others who failed to appear in court, they were outlawed. Reports suggest that, rather than flee from the island, they went into hiding and continued to make whisky illegally.

Whisky Island: This documentary charts life on Islay during the 1960s

Those convicted of excise offences were hardly discouraged. Fines were deliberately set at a low level by the island’s magistrates who knew the offenders as friends, tenants or customers. In 1824, the Scottish Excise Board received a complaint that ‘some of the delinquents have been fined upwards of 30 times, which has no other effect than encourage them’.

After the Napoleonic Wars ended in 1815, greater efforts were made to stamp out the illicit trade and some of Islay’s more ‘responsible’ tenants were encouraged to take out licences to distil. However, while these men might have mastered the art of distilling, most lacked the capital, the business skills or the market contacts – sometimes all three – required to survive the periodic crises which buffeted the industry.

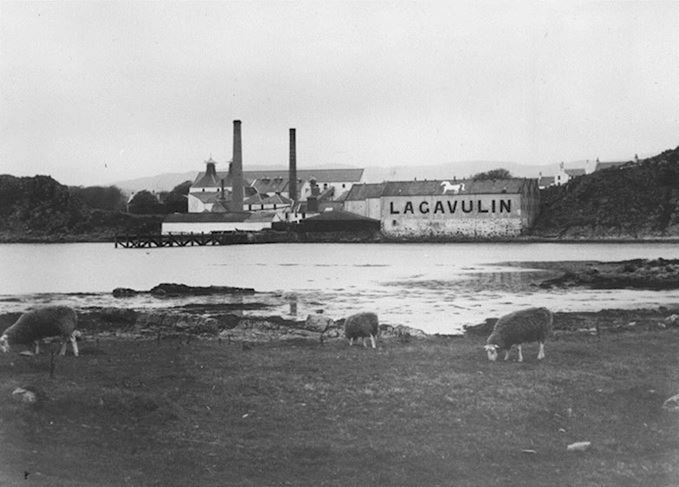

One by one, these small distilleries failed or were acquired by members of the new breed of whisky brokers and blenders emerging on the mainland. Port Ellen was acquired by mainland interests in the 1820s, Lagavulin in 1836, and Bowmore in 1837 – the same year that Ardbeg, which was effectively in liquidation, was rescued by its Glasgow agents.

Islay’s population peaked at around 15,000 people around 1830, with most of the population still living by subsistence farming. During the second half of the century however, much of the rural population was lost through emigration. Many of those who remained were resettled in Port Ellen, Bowmore and other villages, and the distillers began to play an increasingly important role in island life.

Distillery decline: Ardbeg suffered from a lack of investment during the 1970s (Photo: The Glenmorangie Archive)

The distillers lobbied for and provided better piers and sea connections with the mainland. They supplied community leaders such as the Grahams of Lagavulin, the Hays of Ardbeg and, most notably, John Ramsay of Port Ellen. Small coastal villages grew up around the distilleries – Ardbeg, for example, was at one time home to around 200 people and had its own post office, school and billiards hall.

To what extent the people of Islay benefitted from whisky making is open to debate. The distilleries provided an income for hundreds of islanders and their families, but there were very few well-paid positions in management. Company profits were largely repatriated to the mainland. A social divide was exemplified by the fact that, while English was the language of the distillery office, Gaelic remained the predominant language in the maltings and warehouses until the 1960s.

Islay whisky hit new heights of popularity in the 1870s and 1880s, when it was highly sought after to provide body and big, peaty flavour for blended Scotch whiskies. Investment flooded in to the island to extend existing distilleries and to build new ones at Bruichladdich and Bunnahabhain.

Booming business: Ardbeg is now expanding its stillhouse to cope with increasing demand (Photo: Catriona Farquhar)

Yet Islay whisky was always at the mercy of international events. Two world wars, Prohibition in the US and the Great Depression of the late 1920s until the ‘30s resulted in long periods of closure for the distilleries. In the worst cases, Lochindaal closed forever in 1929 and Port Ellen, mothballed that year, did not reopen until 1967. There were years of extreme hardship for those who had been employed at the distilleries or in whisky-related jobs such as peat-cutting and transport.

A new boom in sales of blended Scotch in the 1960s and early ‘70s brought renewed investment in distillery plants and facilities on Islay, but also fuelled the period of overproduction which filled the infamous ‘whisky loch’ of the early 1980s. Islay whisky’s rollercoaster ride continued; the surging worldwide demand for lighter spirits such as vodka, and the change in taste from big and peaty to light and delicate blended whiskies, accentuated the slump in orders for fillings from the island.

Ardbeg closed entirely between 1981 and 1989 and hirpled through the 1990s with little investment. Bunnahabhain closed for two years in 1982 and Port Ellen was closed in 1983 and demolished. Bruichladdich shut in 1995. Job losses affected a significant proportion of a population that had fallen to under 4,000.

Cult following: Islay distilleries such as Lagavulin have enjoyed a resurgence of interest

And then came the single malts revival. A growing interest in traditional foods and drinks, and in products with bold, distinctive flavours, was exemplified by the success of the Campaign for Real Ale in Britain. Journalists like Wallace Milroy, Michael Jackson and Jim Murray began to sing the praises of peaty single malts. Lagavulin acquired a cult fan base after it was included in the ground-breaking The Classic Malts of Scotland selection by United Distillers & Vintners in 1988. Allied Distillers launched the category-defining ‘Love it, Hate it’ campaign which promoted the cult of Islay, and encouraged whisky drinkers to visit the island on a peaty pilgrimage.

Suddenly, Islay was on the rise again. Ardbeg and Bruichladdich reopened under energetic new management. Sales of Islay single malts have increased exponentially. Kilchoman and now Ardnahoe have opened, Port Ellen is to be rebuilt and at least two other distilleries are in the planning pipeline. Islay’s annual Festival of Music and Malt has become one of the most eagerly anticipated events on the world’s whisky calendar, and attracts tens of thousands of visitors.

New era: Young Ileachs, including Bruichladdich’s Christy McFarlane, are choosing to work on Islay (Photo: Bruichladdich)

While the expansion of the whisky industry on Islay has brought well-publicised challenges and inconveniences, there is no doubt it has made a huge contribution to a renewed confidence in Islay’s economy and to the end of nearly 190 years of depopulation. Whisky tourism is a growing island industry. There is a strong interest in exploring ‘traditional’ ways of doing things on Islay; to rebuilding maltings, to working with local barley and to exploring other aspects of Islay ‘terroir’. The distillers have begun grooming young Ileachs for jobs as brand ambassadors and in sales and management – jobs which have been dominated by mainlanders in the past. No one can better communicate the personality of Islay, than a person from Islay.

Islay’s international reputation as the home of big peaty whiskies is now well-established, and the fortunes of the people who live there will be inextricably linked with the industry for the foreseeable future. But the lessons of more than 200 years of boom and bust are that popular tastes are cyclical, that demand for Islay’s single malt whisky can plummet as spectacularly as it can rise.

There is a realisation that the way ahead is to diversify – to produce Islay whiskies that range in flavour from extremely peaty to not peaty at all, as at Bruichladdich, and to develop and promote new types of whiskies and other products such as gin, always with a distinctive Islay character.

Nothing should be taken for granted.