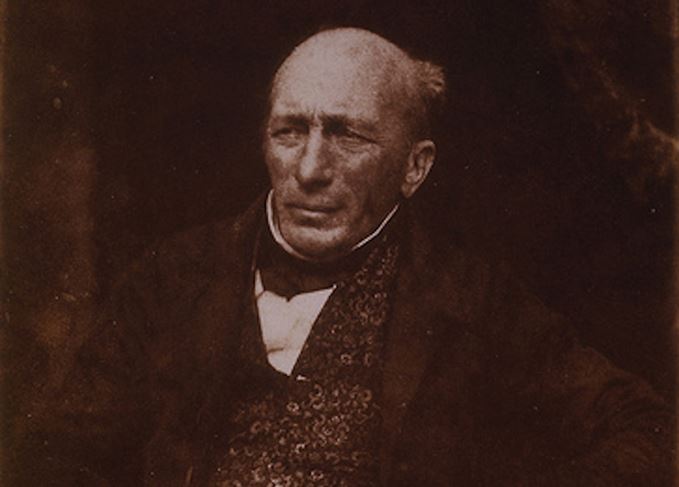

He may have established Glenury Royal distillery, but the whisky achievements of Captain Robert Barclay Allardice pale in comparison with his other exploits. Inexhaustible walker, gambler and pugilist, he was also a friend to Royalty. Iain Russell tells his story.

Of all the enterprising individuals who founded distilleries in the early 19th century, none – not even the legendary Long John Macdonald – possessed the physical strength or inexhaustible energy of Captain Robert Barclay Allardice of Glenury Royal.

Known simply as Captain Barclay (1779-1854), he was one of Britain’s first sporting celebrities, and a keen pugilist who trained England’s champion prize-fighter of the early 1800s. He also won the equivalent of millions of pounds for his triumphs as the country’s leading exponent of ‘pedestrianism’, an extreme form of race-walking.

Furthermore, his feats of strength were legendary: it was said that one of his post-prandial party pieces was to ask a man to stand gently upon the palm of his hand, and then to lift up the fellow and place him atop the dinner table.

Capt Barclay was born on the large family estate near Stonehaven, the son of the Quaker, MP and noted athlete Robert Barclay, 5th of Ury. His father had married Sarah Ann Allardice in 1776 (hence the adoption of the additional surname), and they had eight children before he divorced her on the grounds that she had committed adultery with their footman.

His mother subsequently married the footman and went to live in Norwich. So, when the Captain’s father died in 1797, the youngster stood to inherit the family estate and most of the responsibilities normally assumed by the head of a landed aristocratic family.

He had already succumbed to the joys of gambling and high living while at Cambridge University, however, and become a member of the Fancy – the fashionable set of rich young men willing to sponsor sporting events and wager huge sums on the outcomes. His frequent companion on such occasions was the Duke of Clarence, the future King William IV.

Capt Barclay did not just bet on the performances of other men, however, but frequently backed himself to perform incredibly demanding physical challenges.

His biographer Peter Radford tells how Capt Barclay’s sporting feats became the stuff of legend, reported in the breathless style of the great newspapers of the day.

In 1801, for example, he walked 100 miles in less than 20 hours. In his most famous challenge, he walked 1,000 miles in 1,000 hours for a bet of 1,000 guineas.

Capt Barclay had a particular fondness for physical exertion, as his many wagers attest.

Between prodigious feats of strength, stamina and gambling he found time to serve briefly as the Marquess of Huntly’s aide-de camp during the Napoleonic War. He was appalled at the condition and mismanagement of the Army during the disastrous Walcheren campaign in 1809, however, and returned home to his old ways.

Capt Barclay loved the company of prize fighters, and developed rigorous training regimes for his stable of potential champions. He won the then astronomical sum of £10,000 in wagers when his fighter Tom Cribb defeated the American Tom Molyneaux in 1810.

His ‘system of manly corporeal exercises’ was considered highly effective in the promotion of both physical fitness and moral character, and was touted in the Press as an antidote to the degeneracy and sloth of the youth of the day.

Sporting endeavours kept Capt Barclay away from his Ury estate for much of each year, but he would return to the family home for a month or two each summer.

Ury Castle was reputedly a far from homely place – they say it had no door on the ground level, and visitors had to be hoisted up to the first floor in a basket – but the Captain’s spinster sister Rodney (yes, Rodney) kept house there, with the assistance of a few servants, and there was always a warm welcome for the Captain.

Indeed, the Captain became so fond of one young servant that she had a child by him. He took her off to the south of England and their wealthy neighbours were led to believe they were man and wife.

They had a tempestuous relationship, however, and they did not finally walk down the aisle until Mary was about to give birth to their second child. Sadly, both child and wife died soon afterwards.

On his visits home, the Captain continued the programme of agricultural improvements begun by his father. To encourage local arable farmers, he formed a company, Barclay, Macdonald & Co, to build the Glenury Distillery on the north bank of the River Cowie in 1825. He sold shares to local investors and advertised their whisky in London’s popular sporting periodicals.

The venture got off to an unfortunate start. In April, a fire broke out in the maltings, destroying the kiln, grain lofts and malt barn. The following month, one of the workmen fell into ‘the great boiler’ (probably the mash tun) and was horribly scalded, dying of his injuries soon afterwards.

Glenury Royal was eventually demolished well after Capt Barclay's time, having succumbed to the effects of the whisky loch of the 1980s.

Macdonald appears to have departed the business during the 1830s, and the manager John Windsor became a partner in his place. Things seemed to be looking up, as Windsor was appointed ‘Distiller to Her Majesty’ in March 1838 – it is said that Capt Barclay had petitioned his fellow follower of the Fancy, King William IV, to permit him to use the ‘Royal’ prefix before the King’s death.

The Royal Appointment gave rise to an unseemly quarrel, however, when the irascible Captain Fraser of Royal Brackla took issue with the claim that Glenury was the first to receive the Royal Warrant from Queen Victoria – he claimed to have received his several months earlier.

In later life, Capt Barclay spent more time at Ury Castle, hunting to hounds, walking enormous distances and entertaining on an extravagant scale. He started his own stage coach service between Edinburgh and Aberdeen and often drove long stages himself: indeed, he once drove a coach all the way from London to Aberdeen, stopping only to change horses.

He visited America, where he met President John Tyler, and wrote a book about his adventures. And he claimed the Earldom of Airth which, had he been successful, might have given him a claim to the throne of Scotland.

At the age of 65, Capt Barclay had a son by a young and hard-drinking local girl. She bore him another son when he was 70 and, after the death of the disapproving Rodney, the couple lived together at Ury Castle.

By then, however, the spendthrift Captain had been forced to sell his stake in the distillery and mortgaged his estate to meet huge debts. Old age finally began to take its toll and he suffered a series of strokes in his mid-70s.

He died, in 1854, after being kicked in the head by a horse.