A passionate advocate of Scotch single malt whisky, Wallace Milroy, along with younger brother Jack, will forever be associated with the shop in Soho that bears their name. From possibly apocryphal rugby matches to some ingenious wheeler-dealing, his colourful life is recalled by friend and co-author Neil Wilson.

Wallace Milroy was a giant in the world of Scotch whisky, despite never holding a paid position within the industry. Until he settled with his family in north London in September 1969, he was a nomad in his life and work.

Along with his younger brother Jack, he was largely responsible for bringing single bottled Scotch malt whisky into the on-trade in London, and spent over 40 years brokering export deals, conducting lecture tours and visiting foreign markets. He also wrote one of the most successful pocket guides to malt whisky, which ran to seven editions and sold over 350,000 copies.

Wallace Milroy was born in Dumfries to publicans Wallace and Margaret, who ran the Woolpack Inn on Loreburn Street from 1948. When tasked with his brother to take down ‘the empties’ to the cellar, he discovered how much whisky could be found at the bottom of a discarded bottle and developed a palate for Scotch from that point on.

Schooled at Dumfries Academy, he left at 16 and had an unsuccessful, two-year apprenticeship which his father had arranged in a trade he detested. He never spoke of it and demanded that those who knew never spoke of it either!

Wallace had wanted to join the Royal Navy as a radio operator, but his parents would not agree – so, when his National Service duly arrived, he was grateful to leave Dumfries.

Active service in the Parachute Regiment saw him serve in Aden, Suez and Cyprus. It was not without incident. A wayward American pilot dropped him into a built-up area, where he landed badly on the roof of a two-storey block of flats, and then fell to the street and sustained injuries. He was awarded the Suez Medal and National Service Medal.

Wallace returned to Dumfries, but knew it was not for him, and successfully applied to the South African government to train as a mining engineer and minerals prospector, leaving for Johannesburg in 1952. He was to remain in Africa for the next 17 years.

His parents retired after the demolition of the Woolpack and, after National Service, Jack went into the wine trade to be trained by wholesaler George Sandeman, and was soon promoted to the Trump’s retail chain in Devon, where he learnt a vast amount about fine wine and Champagne.

He then moved to London as the manager and wine buyer of Kettner’s Ltd in Old Compton Street for six years, before taking the lease in Greek Street in 1964 of the Soho Wine Market, where he started to build a business that would eventually become synonymous with single malt Scotch whisky throughout London: Milroy’s of Soho.

Meanwhile, Wallace was spending a lot of time in the bush prospecting, and he once related a story to me that he was picked up from a remote camp by a Rhodesian rugby official who desperately needed someone to fill in at wing-forward to play against a touring team.

Wallace obliged and found that, when he got to the game, he was up against Scotland. He claimed, with a twinkle in his eye, that Rhodesia won the game. I never found any evidence for this and the record books suggest this was one of Wallace’s tall tales.

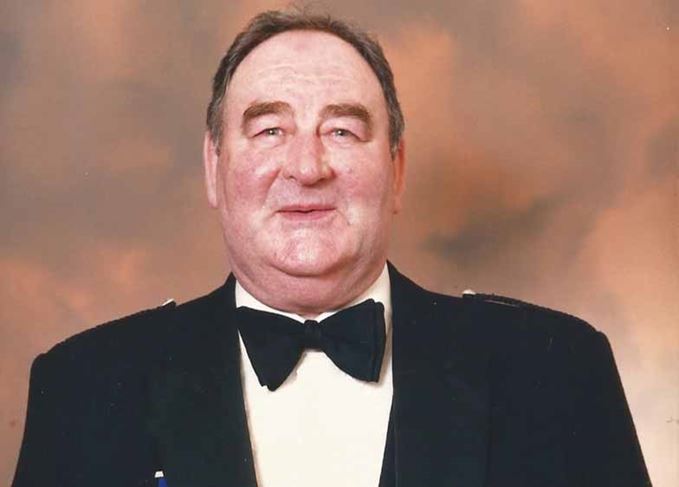

Teller of tales: Wallace Milroy knew how to spin a winning yarn

What was a certainty during that time was that Wallace was investing capital in the business in Soho in order to expand it and allow Jack to create a range of own-label wines for many of London’s restaurants. Jack ensured that Wallace’s supplies of Scotch were maintained with regular shipments to him.

When on annual leave from Rhodesia, Wallace married Jean Craig Anderson in Wick in March 1966 and they returned to Africa, where they settled in Nairobi. With the birth of their daughter Margaret in April 1967 and Craig two years later, the family headed back to London to ensure that the children were schooled in England.

With no firm idea of what he wanted to do, but with a big investment in the business, it was agreed that Wallace should deal with the whisky side – and Jack left him to expand a market that was only represented by four single bottled malts at the time: The Glenlivet, Tomatin, Glenfiddich and Glen Grant. Wallace started to source other single malts, particularly from the Distillers Company, which were unobtainable unless you happened to be a DCL director.

The other aspect that Wallace realised had to be addressed was trade education. He was a dab hand at persuading club and restaurant managers that they needed a comprehensive selection of malt whiskies.

The fact that The Athenaeum eventually created one was solely down to Wallace, of whom Sally Bulloch, the executive manager who took over in 1973, once said: ‘Wallace, who I will be grateful to all my life, took my hand and said: “This is what you have to do, this is what you need.” ’

Another acolyte of the brothers was a certain Crown Prince of a Middle Eastern kingdom who was a frequent visitor to the shop, where Wallace and Jack would teach him all about Scotch in the ‘clanroom’ on the first floor.

In 1984, Wallace undertook a series of lecture tours to university wine societies throughout the UK at the behest of Allen Wood, brand development manager for Macallan at agent Matthew Clark, which culminated in the award of the Macallan Junior Malt Taster of the Year.

As a publisher I then approached him to see if he could supply tasting notes for an idea I wanted to turn into a pocket guide to malt whiskies. He loved the concept and, over the course of the next 14 years and seven editions, we worked together on Wallace Milroy’s Malt Whisky Almanac to create the first practical taster’s guide to Scotland’s malts. That slim volume led to the 1987 Glenfiddich Whisky Writer of the Year Award.

In April 1989 Wallace was inducted as a Keeper of the Quaich, rising to the rank of Master a decade later. He later proposed Bernard Hine and Sugawara-san, the president of the Seven Importers Group of Japan, of which his company Mitsumi was a member, to be inducted as Keepers.

The business, renamed Milroy’s of Soho, prospered under the management of Derek Kingwell and his successor Doug McIvor until 1993, when Jack was forced into a fire sale due to an acrimonious divorce with his second wife. He eventually remarried Mary, his first wife.

Prize-winner: Wallace Milroy’s Malt Whisky Almanac won the 1987 Glenfiddich Award

The business has since passed through a number of hands, but still bears the stamp and brand of Milroy’s. Wallace concentrated on his own wheeling and dealing, something in which he was consummate.

A classic deal he brokered in 1988 came to pass after a wander round Balvenie’s warehouses in the company of Peter Grant Gordon, where he had spotted four dusty casks in a cobwebbed corner.

It transpired that these contained 50-year-old malt, and a deal was agreed that saw Wallace purchasing the resulting 360 bottles at £150 each, selling them on to his Japanese consortium at £360 a bottle and arranging an all-expenses, 30-day, seven-city lecture tour addressing groups of 250 bar and hotel staff on the back of the deal.

After each presentation, all the business cards left behind on the seats were collected by Jack and a winner was drawn, who then received a bottle of the 50-year-old, by then marked up to £1,000 (and now nearer £26,000).

The contacts, of course, all found their way onto the Milroy’s mailing lists, which Jack then exploited to expand his wine sales. After all these events, the audience enjoyed a buffet dinner and tastings of 65 malts and grains, all shipped out by Jack beforehand.

The Milroys knew how to build business at every opportunity but, as Jack commented: ‘We may have mastered the art of using chopsticks, but we never got used to sitting cross-legged on the floor.’

The brothers’ Japan business topped out with several deals in the late ’80s of rare vintage malts, including 30 casks of 25-year-old Springbank and 200 bottles of 1949 Macallan. An additional two container loads of very rare old wines, dating back to 1896 Château d’Yquem, were also shipped to Japan for an upfront payment of £1.4m.

But all these dealings would have been nothing without Wallace’s good humour and wit, which he carried with him everywhere. Once, while staying in the Black Bull Hotel in Moffat with Peter Enright of White Horse Distillers before appearing on Border TV, he answered Peter’s remark that he’d like something light for lunch with the quip: ‘Try balloons on a plate.’

Wallace’s and Jack’s business lunches were infamous. I think I survived at least two, but I can’t be sure. With the Gay Hussar and L’Escargot restaurants close to hand, many trade and business visitors were wined and dined as the Milroys regaled them with stories, many tall, but none dull.

Some of them left wondering if the deal they had just agreed was a good one. Some couldn’t even remember doing deals until the phone rang later and they heard Wallace reminding them of their undertakings.

The aforementioned Middle Eastern Crown Prince became a King and contacted Wallace after he had received a copy of Whisky In Your Pocket, the updated whisky almanac issued in 2010.

He arranged to fly Wallace, Jack, Craig Milroy and Doug McIvor out to his kingdom, where they spent a week being chauffeured round the historical and religious sights. It was, as Wallace stated afterwards, ‘an epic thank you’. In the same year, the brothers received the Lifetime Achievement Award in the Icons of Whisky awards run by Whisky Magazine.

Wallace kept his secrets well. His children never knew that he had been apprenticed to be a hairdresser, and I never knew he was a lifelong Freemason. He is survived by his daughter Margaret and son Craig.