Was Scotland’s national poet really just ‘an Ayrshire peasant, with a peasant’s taste for what was fiery and instant’? He was certainly unafraid of praising whisky in his work – not to mention delving into whisky politics. Gavin D Smith reports.

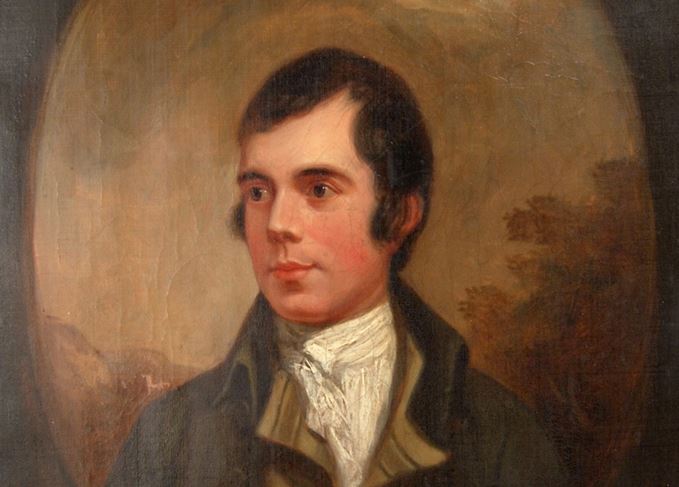

All over the world on 25 January, people gather to commemorate the birth in 1759 of Scotland’s national poet, Robert Burns. As much celebrated in Asia as he is in his native Ayrshire, it is sometimes difficult to separate the myth from the man – and to reconcile the bard’s many contradictions.

The Alloway-born poet and songwriter is sometimes presented as a semi-literate ploughman who just happened to be able to put his thoughts down on paper in a poetic style, but he was, in fact, relatively well-educated and well-read, despite his father, William, being a comparatively unsuccessful farmer.

A passionate advocate of freedom and independence, and an ardent supporter of the French Revolution, Burns nevertheless numbered many titled people among his acquaintances. From 1789 until his untimely death from rheumatic fever on 21 July 1796 he served as that ultimate symbol of authority and order – an excise officer, based in the town of Dumfries.

Many of Burns’ poems and songs feature well-lubricated hospitality, and he specifically wrote in praise of whisky in his epic tale Tam O’Shanter, declaring that:

‘Inspiring bold John Barleycorn [whisky]!

What dangers thou canst make us scorn!

Wi' tippeny [tuppenny ale], we fear nae evil;

Wi' usquabae [whisky], we’ll face the devil!’

From humble beginnings: Robert Burns was born on 25 January 1759 in this unassuming Alloway cottage built by his father, William Burness.

According to legend, Burns was introduced to whisky at the age of 22, when he was an apprentice in the flax-dressing trade in the Ayrshire town of Irvine, prior to taking up farming for a living.

Sometimes, Scotland’s national drink receives a relatively casual mention in his writing, as in The Jolly Beggars (1785), where Burns refers to the whisky from a specific distillery, namely ‘...dear Kilbagie’.

The poem was inspired by a visit made by Burns and a friend to Poosie Nansie’s Tavern in Mauchline. The tavern catered for a less refined clientele – hence the fact that Kilbagie whisky was a favourite drink there.

At the time, Kilbagie distillery, situated at Kincardine, close to the River Forth, distilled spirit in shallow stills which could be run off in a matter of minutes, and the ‘make’ was renowned for its harshness. Much was exported to England and rectified into gin.

Reference to ‘...dear Kilbagie’ is surely then meant ironically, but Aeneas Macdonald in his 1930 volume Whisky declared that:

‘Burns, the arch propagandist of the spirit, was an Ayrshire peasant, with a peasant’s taste for what was fiery and instant... No word of Burns gives the slightest impression that he had any interest in the mere bouquet of what he drank; on the contrary, his eloquent praise is lavished on the heating, befuddling effects of whisky.’

This seems unfair, as Burns elsewhere describes Lowland whisky from the overworked stills of Kilbagie, Kennetpans and the like as ‘...rascally liquor’ and, in his poem Scotch Drink, refers to English brandy as ‘...burning trash’.

As well as making occasional references to the spirit, Burns wrote a number of poems which take Scotch whisky as their central theme, the first being John Barleycorn (1782), which uses personification in referring to the processes of reaping and malting the barley and subsequently distilling it.

As in Burns’ reference to whisky in Tam O’Shanter, there is a clear message that whisky invokes a sense of bravery.

‘John Barleycorn was a hero bold,

Of noble enterprise;

For if you do but taste his blood,

‘Twill make your courage rise.

‘Twill make a man forget his woe;

‘Twill heighten all his joy;

‘Twill make the widow’s heart to sing,

Tho’ the tear were in her eye.’

Burns went on to compose two altogether more ‘political’ whisky poems, both of which were inspired by perceived injustices towards Scotland’s interests and her people.

Scotch Drink was written during the winter of 1785/6, the year after new excise legislation in the form of the Wash Act had ended the exemption of duty payments enjoyed by the Protestant Forbes family’s Ferintosh distilleries in Ross-shire.

Forbes’ estates had been badly damaged during the Jacobite rising of 1688 in support of the Catholic James III and, by way of compensation, the Scottish Parliament granted Forbes the right to distil whisky without payment of duty in perpetuity, in return for the sum of 400 Scots marks per year.

Not surprisingly, the Forbes family became very wealthy during the following century.

The Wash Act led to them being awarded £21,580 in compensation, but Robert Burns was outraged by the loss of the Ferintosh ‘privilege’, and was moved to put pen to paper on the subject.

Much of the lengthy poem is taken up with praise for Scotland’s ‘native’ drink, with stanzas such as:

‘O thou, my Muse! guid auld Scotch drink!

Whether thro’ wimplin’ [twisting] worms thou jink

Or, richly brown, ream [foam] owre the brink

In glorious faem

Inspire me, till I lisp an’ wink

To sing thy name!’

Ultimately, however, the poem shifts from being a celebration of Scotch whisky to tackle the Ferintosh situation, and the apparently repressive nature of prevailing excise legislation, perceived by the writer as anti-Scots, anti-poor and anti-freedom.

He writes:

‘Thee, Ferintosh! O sadly lost!

Scotland lament frae coast to coast!

Now colic grips, an’ barkin’ hoast [cough]

May kill us a’

For loyal Forbes’ charter’d boast

Is taen awa!

Thae curst horse-leeches o’ th’ Excise

Wha mak the whisky stells their prize!

Haud up thy han’, Deil! ance, twice, thrice!

There, seize the blinkers!

An’ bake them up in brunstane [brimstone] pies

For poor damn’d drinkers.’

Burns returned to the topic of whisky in 1786 with The Author’s Earnest Cry and Prayer – addressed to ‘The Right Honourable and Honourable Scotch Representatives in the House of Commons’.

It is a passionate polemic penned for the 45 Scottish representatives in the House of Commons, written in response to the Scotch Distillery Act of 1786, which imposed an extra duty on Scottish spirits exported to England, making it much more difficult for Scottish distillers to do business there.

The resultant poem is quintessentially Burnsian in its righteous eloquence on the notions of nationalism, individual rights and the use and abuse of power. The poem concludes with one of Burns’ most quoted couplets about whisky:

‘Freedom and whisky gang thegither,

Tak aff your dram!’

An apt toast for us all, perhaps, on 25 January…

Intrigued by Burns' poems-turned-toasts? Discover the whisky industry's favourite Scottish toasts by Burns and other bards.