It seems only fitting that on St. Patrick’s Day (17 March) we widen our remit ever so slightly and look at the close, if sometimes fractious, relationship between Scotch and Irish whiskies.

These good-humoured debates are often held in a pub, in Ireland mostly, over glasses of stout and multiple glasses of fine Irish whiskey. They often get bogged down in the ‘who was first?’ argument [answer, we don’t know], followed by ‘what’s so wrong with your whiskey that you have to distil it three times?’, which is immediately countered with ‘why can’t you spell?’

The fact is that the roots of both nations’ whisky-making are shared. Take Usquebaugh for example, that extravagant whisky style, flavoured with spices, and fruits, often tinted with saffron. It was made in both countries from the 16th century, but known primarily as an Irish specialty up until the late 19th century.

We love the romaticised tales of 18th and 19th century Scottish whisky smugglers, but small-scale rural Irish distillers were hit with the same laws and reacted in the same way, by going underground. At root, the spirit was the same.

The smuggling era was also the time when large-scale commercial distilling was growing in importance. In Ireland, this was concentrated primarily in the cities – Dublin especially, while in Scotland it started in Clackmannan and Fife, before becoming urbanised. It was this shift in scale and intent which would create the foundations for blended whisky in Scotland and single pot still whiskey in Ireland.

The other topic in the never-ending debate is ‘who was the father of Irish whiskey?’ The response is usually: ‘John Jameson’.

‘OK, but where was he born?’ I respond. There’s often a brief pause.

‘Dublin?’ someone ventures.

‘No. Alloa,’ I reply. Yes, Jameson was Scottish. What’s more significant is that he was related by marriage to one of the two mightiest Scottish distilling dynasties, the Haigs, who themselves had married into the then even more powerful Stein family.

Between them, at the end of the 18th century, the two families controlled over 50% of Scotland’s entire whisky production and had the monopoly of the lucrative English export trade. The Steins owned Kilbagie, Kennetpans, Dolls, Canonmills, and Hattonburn; the Haigs had Lochrin, Kincaple and, in 1817, built Cameronbridge.

John Jameson, regarded as the founder of Irish whiskey, was in fact Scottish.

The Haigs were also looking further afield. In the late 18th century, Robert Haig built one (and possibly two) distilleries – Dodder Bank in Dublin. It was the start of a significant investment in the new Irish whiskey industry by both families.

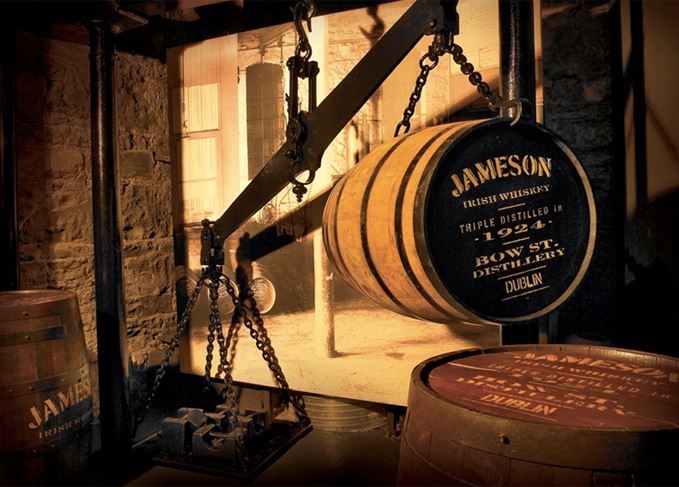

In 1751, John Haig of Lochrin married Margaret Stein. In 1768, their eldest daughter, also Margaret, married John Jameson. Soon after, they moved to Dublin where John took a share in a small distillery in the city’s Bow Street.

Around this time, John Stein Jr of Kennetpans also saw potential rich pickings in Ireland. He built a distillery in Dublin’s Bow Street, another in the city’s Marrowbone Lane as well as distilleries in Clonmell and Limerick (Thomond Gate, which was then bought by Glasgow distiller Archibald Walker in 1879.

It’s often thought that Stein employed Jameson but Carol Quinn, archivist at Irish Distillers, can find no record of this and believes that there were two separate sites in Bow Street, with Jameson’s distillery eventually swallowing up Stein’s plant.

The two families clearly got along, however. John and Margaret Jameson’s son, John Junior, married Isabella Stein, (John Stein Jr’s daughter). Another son, William, worked at Stein’s Marrowbone Lane distillery. On William’s death in 1802, his brother James took over and, in 1822, bought the distillery outright. Another son, Andrew, ran a distillery in Enniscorthy, Co.Wexford. He was, incidentally, Guglielmo Marconi’s grandfather.

By the mid-19th century Irish whiskey was the gold standard in terms of character and quality, thanks to the development of the style now known as single pot still: triple distilled, and made from a mix of malted and unmalted barley. This mashbill is often thought of as a wholly Irish invention, but the mixing of malted and unmalted was commonplace in both countries in the 18th and 19th centuries. What the Irish distillers did was refine and perfect the technique.

Equally significantly, what John Jameson Junior and his fellow distillers did was establish consistency in their makes. They also went another step further than their Scottish colleagues (and relatives) by branding their names on the casks (then labels, then capsules), which they sold to merchants. Their name was their bond. It was a strategy which would be taken up by Scottish blenders.

Such was the success of Irish whiskey that by the 1880s Cameronbridge distillery was making ‘Pot still Irish’. The Irish taught the Scots the importance of consistency, and how to commercialise whisky.

Ireland's single pot still whiskeys, like those above, are changing consumers' perception of whisky.

The Cameronbridge copy was an exception however. The Scots reacted to Irish dominance of the whisky market by blending together single malt and a new type of whisky which also had shared Irish and Scottish parentage – grain.

The 19th century is when the world sped up, when ‘inefficiency’ was the enemy and engineering could not only save time, but increase profit. In whisky this resulted in the invention of the ‘continuous’ still. The first was invented by Robert Stein in 1827 and installed at John Haig’s Seggie distillery in 1830. Stein stills would run in some Scottish distilleries until the early 20th century in parallel with the second type of still, that invented by Irishman Aeneas Coffey, whose design is still used.

It’s been often said that the Irish rejected the column still. They didn’t. There were 13 Coffey stills operational there by the end of the 19th century.

The arrival of grain ushered in a direct challenger to Irish single pot still – blended Scotch. Irish whiskey arguably still had the better reputation however, which is why Scottish and English distillers began shipping grain whisky to Ireland, blending it with a little single pot still and then re-exporting it to England as ‘Irish whiskey’. This was a step too far for the Dublin distillers. In a remarkable 1879 tract, ‘The Truths About Whisky’ (no ‘E’ by the way, my Irish chums) the two Jameson firms, Powers and George Roe, set out the case against the insidious creep (as they saw it) of grain and blends. They were not only protecting their style but the good name of Irish whiskey which for them could only be single pot still.

As we know, grain and the blenders won out and the balance of power shifted. By the start of the 20th century the Scottish grain distillers, most of whom we know trading as DCL, aimed to control supply. That meant buying, and then closing, six of Ireland’s grain plants, consolidating production in Scotland.

Independence, Prohibition, trade wars, embargoes, economic depression and world wars then combined to virtually shut down the entire Irish whiskey industry. It survived though and is now prospering once more. Thirty new distilleries have applied for planning, while the Irish approach to single malt, single grain and, yes, blends continues to win new friends – and rightly so. At the head of it all is single pot still, the style which helped to change people’s perceptions of what whisky, whatever way you spell it, could be.

Happy St. Patrick’s Day! Who, by the way, was either Scottish or Welsh…