Westcombe Dairy, nestled in the south-west of England, is on a quest to revolutionise the cheesemaking industry. It’s a familiar tale told throughout the whisky world: merging traditional practices with modern, innovative ideas. Fiona Beckett visits the site that’s bringing Cheddar into the 21st century, and finds some whisky matches along the way.

You might think the production of Cheddar was steeped in tradition. Yet one cheesemaker, Tom Calver of Westcombe Dairy in Somerset, is using some of the most up-to-date technology to improve the quality of his family’s farmhouse cheese.

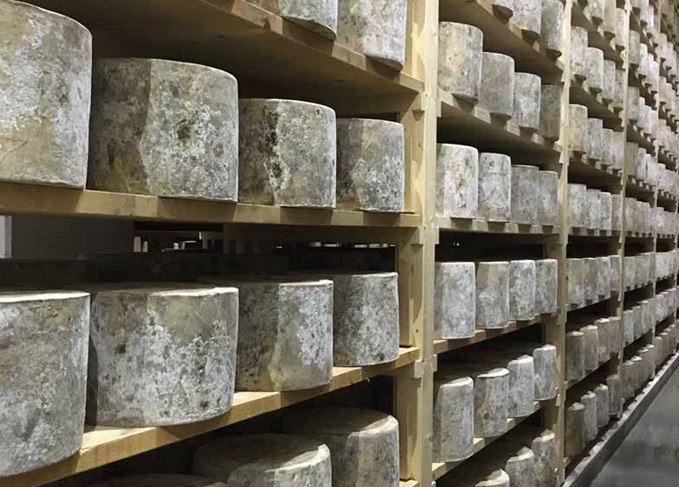

As you stand in his impressively modern cellar, which is built into the hillside overlooking the dairy, you hear a whirring and clicking noise that sounds like R2D2 has been let loose. Not far wrong – a giant robot is moving up and down the shelves, pulling out and turning the huge 25kg cheddar wheels. Nicknamed ‘Tina the Turner’ by media-savvy Calver, it can work round the clock, meaning the cheeses can be turned more frequently.

Calver discovered the machines during a trip to Jura in France, where they are used to handle similarly weighty Comté cheeses. Cheddars are a different shape, so they had to get the Swiss manufacturer to modify the turning mechanism and brush to Hoover the cheese, rather than wipe them – a process of adaptation that took three years.

Tina finally came into use in September 2015 with an immediate benefit to the quality of the cheeses. ‘We haven’t had to get rid of any workers,’ Calver hastens to assure me, ‘and, frankly, it’s back-breaking work. It just means our cheeses are turned more efficiently and more often. We can now move them every week to 10 days. Previously, they’d only get turned every two to three months.

‘The cheeses look so much happier,’ he says, patting one fondly. ‘The mould growth is better and the mite control a thousand times better – and that benefits the flavour.’

Manual labour: Technology has not lessened the need for skilled cheesemakers, says Calver

Tina is not the only high-tech innovation 35-year-old Calver has introduced. Each cheese is now chipped electronically. ‘You can scan them and the results pop up on your iPhone or iPad,’ he enthuses, obviously thrilled with his RFID (radio frequency identification) scanner.

‘It tells us exactly when the cheese was made, and the temperature and acidity of the milk. We used to write all that down and stick it in a folder, then hardly ever look at it. Now we can see it at a click. We’re working on a second version called “cheese tracker” we can roll out to other cheesemakers.’

However, the process hasn’t become so mechanised that it’s done away with human input altogether. The quality assessments are still carried out in the traditional way with a tasting iron. ‘Sometimes you have to go with your gut and decide which wheels have the potential to make a better cheese,’ says Calver, calling to mind a master distiller discussing his or her beloved casks of maturing whisky.

He shows me a 14-month-old Cheddar that was made in September 2015, which is totally different from a cheese that was made the week after. ‘This is what you get with unpasteurised milk,’ he explains. ‘It’s about character and terroir, not consistency. Having a variety of cheeses to pull from is really quite a thing.’

Like whisky, there is an ‘angel’s share’ component to ageing cheddars – the moisture loss intensifies and concentrates the flavours.

The creation of the cellar, which was started in 2014, was a massive logistical exercise. ‘We had to move 15,000 tonnes of earth into the fields behind,’ says Calver. ‘Then we moved across 4,500 cheeses from the old cellar in the space of five days.’

He’s particularly proud of the low energy consumption of the cellar, which is regulated by a cooling system that runs off spring water from the hill at the back. ‘The whole system uses half a kilowatt of energy when it’s on – that’s about a third of the consumption of a domestic kettle.’

It’s been a massive investment for the family – around £170,000 for Tina the Turner alone: ‘Which is actually not bad when you compare it to the cost of one of dad’s combine harvesters.’

But, as Calver points out: ‘We’ve been farming here for 100 years and want to be here for another 100 years to come.’ They hope to recuperate part of the cost by ageing other farms’ cheeses as they do at Jasper Hill in Vermont. ‘We’re only making around 5,000 at the moment. We’ve got the capacity to age over 6,000.’

Tom Calver: The innovative dairy farmer has converted an old phone box into a smoker

‘I’d like to change the attitude of the dairy industry,’ he continues. ‘It pisses me off listening to farmers moaning about milk prices. We could find small farmers who are farming in a good, sustainable way and teach them how to make Cheddar, then bring it here to age it.

‘Cheddar is the most produced cheese in the world, but 99% of it is bland and boring. It needs to change from being a commodity-based product to a quality one, but farmers have to ask themselves: “Can we make the cows [the Calvers farm mainly Holstein Friesians] more comfortable? Do we plant crops to give them a wide, diverse diet, or is it just a question of squeezing more milk out of them?” If the cows are happy, their milk becomes rounder in flavour.’

Calver is also experimenting with ageing his cheeses for longer. I try a gorgeous 18-month-old Cheddar with a woody, almost oaky character that he aptly describes as ‘having a nice warm hug’.

As I leave, I spot a phone box outside, which it turns out has been converted into a smoker. You almost expect it to open up like a TARDIS. Knowing Calver, it probably does.

Whisky and Cheddar

Given that the full flavour of a West Country Farmhouse Cheddar defeats many wines, Calver reckons Scotch whiskies, particularly Sherry cask-aged ones, are a great match. I can certainly vouch for The Glenlivet Founder’s Reserve with a sliver of Westcombe; a relatively light, fragrant whisky like this would suit younger, medium-matured Cheddars.

Meanwhile, a more intensely-flavoured mature Cheddar like the older Westcombes would benefit richer, sweeter, more heavily Sherried whiskies like Aberlour a’bunadh.

More information on what Calver and his father Richard are doing can be found via the BBC’s On Your Farm programme.