Not so much whisky heroes as whisky villains: if Robert and Walter Pattison epitomised the late Victorian Scotch whisky boom, their subsequent fall from grace ushered in a grim new era of austerity. Gavin D Smith tells a tale of flamboyance, fraud and 500 talking parrots.

Back in the 1890s, blended Scotch whisky was riding high. It had replaced brandy as the English gentleman’s spirit of choice and was fast becoming a drink for the world. At the forefront of the blended Scotch revolution were household names like John Walker & Sons, John Dewar & Sons and James Buchanan & Company, but one now much less well-known firm was at the centre of activities that effectively turned ‘boom’ to ‘bust’. That firm was Pattisons Ltd.

The Pattison family had started out in business as Edinburgh dairy wholesalers, with patriarch Walter Pattison also acting as an insurance agent. He was joined in the firm by sons Robert and Walter, and in 1882 Pattison, Elder & Co was formed, with the brothers at the helm and Alexander Elder as a partner.

Recognising that Scotch whisky was a lucrative trade to be involved in, the Pattisons began to blend and market their own whiskies from 1887, with their principal brands including Morning Dew and Royal Gordon. In 1889, the brothers made a profit of around £100,000 when the company was floated on the Stock Exchange.

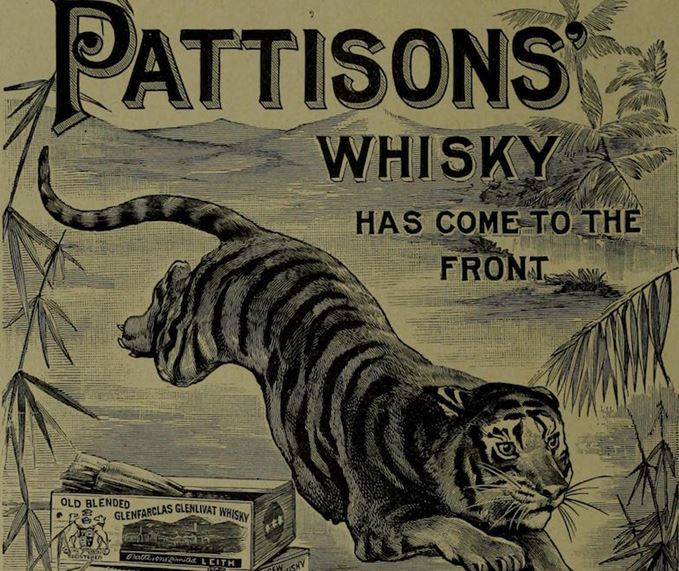

They used the medium of advertising with great skill and verve, tapping into the prevailing public pride in the British Empire and its military might. During 1897, the Pattisons reputedly spent the vast sum of £20,000 on advertising, and three times that the following year.

Probably their best-known ploy was to have 500 African Grey parrots trained to repeat phrases such as ‘Buy Pattisons’ Whisky!’, before giving the birds away to publicans all over the country.

The brothers operated in a notably flamboyant manner, with palatial, marble-clad offices in Leith’s Constitution Street, Edinburgh townhouses, and country retreats at Clovenfords, near Galashiels, and Peebles in the Scottish Borders.

One of their favoured methods of garnering publicity was to arrive at Galashiels or Peebles railway station slightly too late to catch the early morning train into Edinburgh, and – having made sure that the local press was alerted – they would hire a private train at a cost of £5 1s-per-mile to transport them to their important business meetings in the capital.

In 1896 their company was floated as Pattisons Ltd, with capital of £400,000, and in order to secure supplies of spirit for blending, a half-share in Glenfarclas distillery was acquired, while the firm also had substantial interests in the Oban & Aultmore-Glenlivet Distilleries Ltd and Ardgowan grain distillery. The Pattisons even diversified into brewing, with the acquisition of Edinburgh’s Duddingston brewery.

Boom to bust: the Pattisons’ marketing genius concealed an inherently weak business

Boom to bust: the Pattisons’ marketing genius concealed an inherently weak business

Outwardly, Pattisons Ltd seemed to exemplify everything that was positive and entrepreneurial about Scotch whisky in the late Victorian era, but all was not what it seemed.

Such was their extravagance that, in order to keep all their plates spinning, as it were, the brothers adopted the practice of over-valuing property in the company’s possession and buying back at higher prices whisky stocks which they had previously sold.

The result was that, on paper, the value of their stocks was substantially higher than they were in reality. The Pattisons also paid shareholder dividends from capital in order to reassure investors that all was well – though there had been rumours of Pattisons’ financial fragility as early as 1894.

Nonetheless, July 1898 saw the announcement of record profits and plans to launch a new branded blend and to extend Aultmore and Glenfarclas distilleries. The plates could not stay in the air forever, however, and a slight downturn in the whisky industry was enough to send them crashing to the ground – as the business model employed by the Pattisons could only work in an expansionist environment.

On 5 December 1898, Pattisons’ cumulative preference stock plummeted by 55%, and a few days later the Clydesdale Bank refused to extend the company’s credit, leading to the start of formal liquidation proceedings.

Once these proceedings were under way, it became clear that around £500,000 could not be accounted for, with company assets amounting to less than half that figure.

Robert and Walter Pattison were subsequently tried and convicted of fraud and embezzlement. In 1901, Robert was jailed for 18 months, while younger brother Walter served nine months in Perth General Prison.

The ‘Pattison Crash’ did not only affect the company and its staff, but also unsecured creditors. Nine other businesses failed as a result, and many small-scale suppliers also went out of business. Whisky prices fell, with obvious consequences for the entire Scotch whisky industry.

Indeed, distillery construction, which had been so prolific during the previous few decades, came to an abrupt halt. The architect Charles Doig was responsible for the design of Glen Elgin distillery, which opened in May 1900, but closed just five months later.

At the time, Doig predicted that no new distillery would be built in the Scottish Highlands for 50 years, and his prophecy proved uncannily accurate, with Tullibardine in Perthshire being the next to be constructed – in 1949.

Clearly, Walter and Robert Pattison alone did not cause the ‘crash’, but were merely catalysts of the crisis that hit the Scotch whisky industry, and ‘boom’ would have turned to ‘bust’ before too long in any event, as the level of stocks being accrued bore little relation to the level of sales.

The Pattisons were not alone in being determined to believe that the good times would last forever, but the spectre of over-production was never far from the feast, with many new distilleries vying with existing, and often expanded, operations.

In The Making of Scotch Whisky, Moss and Hume note:

‘Stocks were built up...to ridiculous levels... The annual increase in stock warehoused in Scotland rose from just under 2,000,000 gallons [9m litres] in 1891-2 to 13,500,000 gallons [61.3m litres] in 1897-98 and 1898-9 net additions to stock amounted to 40% or more of total output.’

Many years after the ‘Pattison Crash’, DCL’s chairman and managing director WH Ross wrote:

‘...so large were their transactions and so wide their ramifications that they infused into the trade a reckless disregard of the most elementary rules of sound business… Investors and speculators of the worst kind were drawn into the vortex and vied with each other in their race for riches.’

With the demise of Pattisons Ltd, the world of Scotch whisky may have gained greater probity, but it undoubtedly lost some of its colour along the way.