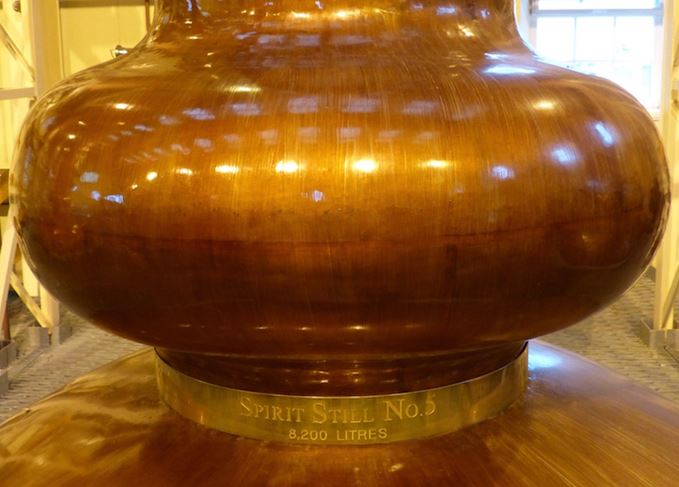

To many, the sight of a burnished, shiny set of copper pot stills is one that sums up Scotch whisky. But why copper? It may appeal aesthetically, but what are the practical reasons for its continued use in distilleries old and new? Let’s hear what the Whisky Professor has to say on the subject.

Dear Whisky Professor,

On a recent visit to Scotland for a concert tour with my stepchildren (a group of seven singers – a bit like The Osmonds, but Austrian), I took the opportunity to visit a local whisky distillery.

While there, I was very much struck by the imposing size and shape of the stills, and their lustrous copper sheen. They really were very beautiful, but nonetheless something about them struck me as rather odd.

Now, I have a bright copper kettle in my kitchen; along with raindrops on roses and warm woollen mittens, it is among my favourite things, and a particular joy when recovering from mishaps such as bee stings and dog bites.

However, it has long had a purely ornamental role in the Alpine villa we call home – I find my 3,000-watt De’Longhi digital jug kettle far more suited to the swift preparation of coffee, tea and other hot beverages.

So my question is this: why have Scotch whisky distillers not moved with the times and installed stills made from some versatile and long-lasting modern material such as stainless steel or aluminium? Why, indeed, are whisky stills still made from copper?

Yours,

Maria von Trapp (Mrs),

Villa (high on a hill, just past lonely goatherd),

Nr Salzburg, Austria.

Precious metal: Copper is more than just a pretty face, says the Whisky Professor

Dear Mrs von Trapp

How, indeed, do you solve a problem like Maria’s?

First of all, stills weren’t always made from copper. The earliest examples would have used whatever durable and malleable material came to hand, such as ceramics or glass.

But copper was soon fixed upon as the ideal material with which to manufacture pot stills. It is relatively easy to mould and shape into whatever form you wish; it conducts heat easily and efficiently; and it is resistant to corrosion.

Nonetheless, it does wear out and it is expensive, prompting distillers to experiment – as you suggest – with newer, cheaper and more durable materials, such as stainless steel. This happened particularly, but by no means exclusively, in the United States.

However, early adopters of stainless steel quickly noticed a dramatic change in spirit quality – an unwelcome, sulphurous odour that had nothing to do with cut points or the speed at which the stills were run.

Distillers had arrived at copper as the ideal still material by a process of trial and error; now they uncovered a hidden benefit of the metal by the same method, a benefit confirmed by further investigation and experimentation.

Think of copper as a ‘silent contributor’ to spirit quality; the availability of clean copper inside the still is vital to allow complex chemical reactions to take place, removing highly volatile sulphur compounds – chief among them dimethyl trisulphide or DMTS – and helping in the formation of esters, which tend to give the spirit a fruity character.

This process is also absolutely vital when making grain whiskies in column or continuous stills, where copper may be used in the manufacture of the sides of the stills or the plates themselves. Here, copper does its best work in the rectification system, where the unwanted compounds are mainly concentrated.

But copper’s importance extends beyond the stills themselves to the apparatus used to condense the distilled spirit vapour. In malt whisky distilleries, these are typically of two types – shell-and-tube or worm tubs – and both use copper.

Available copper: Shell-and-tube condensers tend to produce lighter spirit

Worm tubs consist of copper coils submerged in tubs of cooling water, but the shell-and-tube construction has much more ‘available’ copper, meaning more copper contact with the condensing spirit and producing typically lighter, fruitier and grassier flavours in the mature whisky.

By contrast, worm tubs tend to yield more sulphury, meaty or vegetal notes, simply because the copper has had less opportunity to react and remove those flavours. Deposits will also gradually build up on the inside of the ‘worm’, reducing the copper’s reactivity further.

Although the removal of these volatile sulphur compounds is generally desirable during the distillation process, the extent to which it happens – governed by a variety of factors from still shape and size through to method of condensation – is also a stylistic decision.

You want a funky, meaty, slightly sulphury new make? Then you need a distillation process that involves less copper contact (and worm tubs). Looking for fruity, grassy spirit? Make the most of every inch of copper in your stills and fit shell-and-tube condensers.

Taking this stylistic choice a stage further, some distilleries are now fitting stainless steel condensers – Ailsa Bay, for example – to give them an option that has less copper contact and a different style of whisky as a result.

There are two further consequences of the complex reactions that occur when spirit and copper interact. The first is that, as the reactions take place, the spirit ‘picks up’ copper in a soluble form.

Only very small amounts of this will be present in the final product (you’ll be relieved to hear); most of it is discharged long beforehand, incidentally posing an environmental challenge to distilleries. That blue stuff you see in the spirit safe? Copper salts or, more accurately, copper carbonate.

Blue stuff: Copper carbonate deposits in Lagavulin’s spirit safe

The other effect is that, in certain parts of the still where more of the beneficial catalytic reactions occur – above the boiling line, in the shoulder, swan neck, lyne arm, condenser and at the start of the worm – the copper will gradually erode.

As the copper thins, it is not unknown for a still to ‘pant’ like an over-exerted dog, its shoulders rising and falling under the strain. Repair or replacement needs to take place swiftly to avoid a collapse.

To sum up, although expensive, copper has great properties of malleability, thermal conductivity and resistance to corrosion. Its ultimate weakness – that, especially in certain places, it wears out – is also one of its greatest strengths, since it is by this copper ‘sacrifice’ that the spirit that will become whisky is refined and stripped of unwanted odours and flavours.

No wonder, then, that distillers will sometimes refer to the presence of what they call ‘sacrificial’ copper in continuous or stainless steel stills: copper installed not because of aesthetics or distillation efficiency, but for reasons of spirit quality.

In other words, copper is much, much more than just a pretty face. I hope that answers your question.

So long, farewell, auf wiedersehen, good night.

Yours aye,

Prof

Do you have a burning question about Scotch whisky for the Whisky Professor? Email him at [email protected].