Known for his strong aversion to blended Scotch, pseudonymous author Aeneas MacDonald was opinionated, observant and masterful with words. His book ‘Whisky’ gave huge insight into the industry, during times of great change for Scotch. Gavin D Smith recounts the writer’s past.

When no less an authority than Dave Broom describes something as ‘the finest whisky book ever’, it’s time to pick up a copy and see what the fuss is all about.

The volume in question is simply titled Whisky, and it was written by one Aeneas MacDonald, published by Edinburgh’s Porpoise Press in 1930. First editions are highly sought-after, but publisher Birlinn has produced a handsome new edition this year, including an excellent Appreciation by Ian Buxton.

Remarkably, considering that the recorded history of Scotch whisky dates back to 1494, this was the first book to be written about the subject for the general reader, so it deserves our interest and respect for that alone. It is also, however, a highly entertaining read: personal and opinionated, and providing a valuable insight into the Scotch whisky industry during that curious period between the two World Wars, when the status of Scotch whisky was at a relatively low ebb.

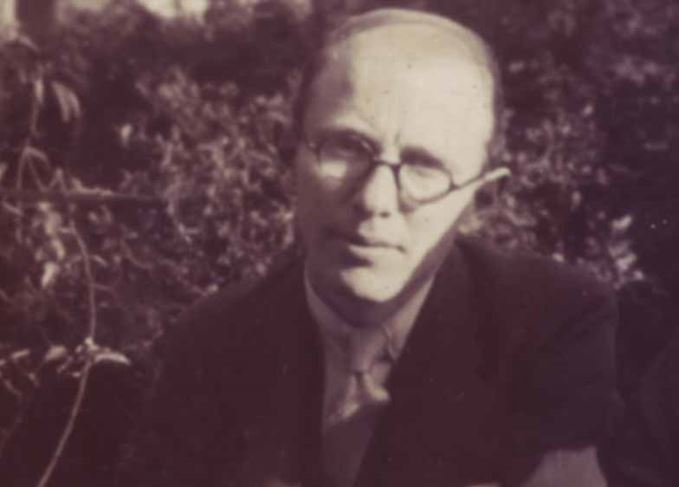

Aeneas MacDonald was a pseudonym adopted by Leith-born George Malcolm Thomson (1899-1996), a graduate of history and English literature from Edinburgh University. He was co-founder of the Porpoise Press, which published books by some of Scotland’s leading young authors during the 1920s. These included the likes of Hugh MacDiarmid and Neil Gunn, both passionate advocates of Scottish independence, and Scottish nationalism was a cause dear to Thomson’s own heart.

Thomson was active as an author on Scottish subjects, and later worked as a long-standing London-based journalist for the Beaverbrook newspaper empire, before becoming a more prolific author following his retirement from journalism.

The writer only assumed the pseudonym ‘Aeneas MacDonald’ for one of his many books, and the most commonly-accepted explanation is that he did not wish to upset his mother, who was a staunch teetotaller.

In taking the name, the nationalist and history graduate was acknowledging the significance of the 1745/46 Jacobite Rising, which failed to put a Stuart – ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’ – back on the throne of Britain. The ‘real’ Aeneas MacDonald was a Scot exiled in Paris, like Charles Edward Stuart, who accompanied the prince and his followers on the ill-fated venture to restore a Stuart monarchy.

In writing Whisky, MacDonald clearly saw the perceived decline of interest in Scotland’s national drink as symbolic of the state of Scotland as a whole at that time, and he was undoubtedly a whisky purist, setting pot still single malt on a pedestal, while the product of the column still was largely a thing to be despised. He wrote that: ‘… The decline of whisky as a civilised pleasure is linked with the decay of taste in Scotland.’

In 1930, the world of Scotch whisky was undoubtedly in a state of decline, one that essentially lasted for the best part of the first half of the 20th century, following the collapse of the great Victorian whisky boom – led by the growth in popularity of the blended whisky largely despised by MacDonald.

New edition: ‘The finest whisky book ever’ was republished earlier this year by Birlinn

Yet, as MacDonald noted: ‘There are, at the time of writing, 122 distilleries in existence in Scotland. Of these, ten make Islay whiskies; ten are in Campbeltown; eight make Lowland malt; one makes both grain whisky and Lowland malt; nine produce a grain whisky; and by far the greater number, eighty-four, distil Highland malt whisky.’ Today, the overall figure stands at around 114, though many have much larger capacities than those active in 1930.

Whisky is a romantic’s and a poet’s book about whisky; it is not filled with statistics, but with heartfelt observations. It is written by someone who loves language and uses it supremely well. Probably the only other book on the subject with as much lyricism and ‘soul’ is Whisky and Scotland, written five years after MacDonald’s volume, by his friend, fellow nationalist and Porpoise Press author, Neil Gunn.

The tone is set on the first page of Whisky, when MacDonald writes that: ‘… It is opportune that a voice be raised in praise of this great, potent, and princely drink where so many seek to slight and defame, and where so many glasses are emptied foolishly and irreverently in ignorance of the true qualities of the liquid and in contempt of its proper employment.’

The book is worth reading for the ingenious ‘Rhymed Guide’ to Scotland’s distilleries alone, which includes the following verse about Campbeltown’s distilleries and characterful whiskies, now almost entirely consigned to the pages of history:

‘Last port seen by westering sail,

’Twixt the tempest and the Gael,

Campbeltown in long Kintyre

Mothers there a son of fire,

Deepest-voiced of all the choir.

Solemnly we name this Hector

Of the west, this giant’s nectar:

Benmore, Scotia, and Rieclachan,

Kinloch, Springside, Hazelburn,

Glenside, Springbank, and Lochruan,

Lochhead. Finally, to spurn

Weakling drunk and cowards sober,

Summon we great Dalintober.’

MacDonald provides a comprehensive, if partial, history of whisky, and fascinating descriptions of its production. Again, this throws a valuable light on an era when distilleries still needed to be close to a source of peat for malting, stills were heated by coal, and there was not a microprocessor in sight.

We began by quoting Broom on Whisky, so let us bookend that with a quote by no less an eminence than Charles MacLean. ‘If I could take only one whisky book to a desert island, it would be Aeneas MacDonald’s Whisky.’

If you were allowed to take a dram to accompany your reading matter, Aeneas MacDonald would doubtless have strong opinions on what it should be. Best, perhaps, not to mention discounted supermarket own-label blends…