Pick any pre-1990 Sherried Scotch whisky, and there’s a chance those Sherry influences had a helping hand from paxarette. While this cask conditioning agent is now banned in Scotland’s distilleries, The Whisky Professor investigates how it came to be used in Scotch in the first place.

Dear Prof,

I read recently about something called paxarette, which apparently was used in the Scotch whisky industry for many years, but is now banned. What was it, and why did the ban happen? Was it harmful to health? If so, would I be in any danger if I drink a whisky in which it was used?

Rosie Wyatt, Kilwinning

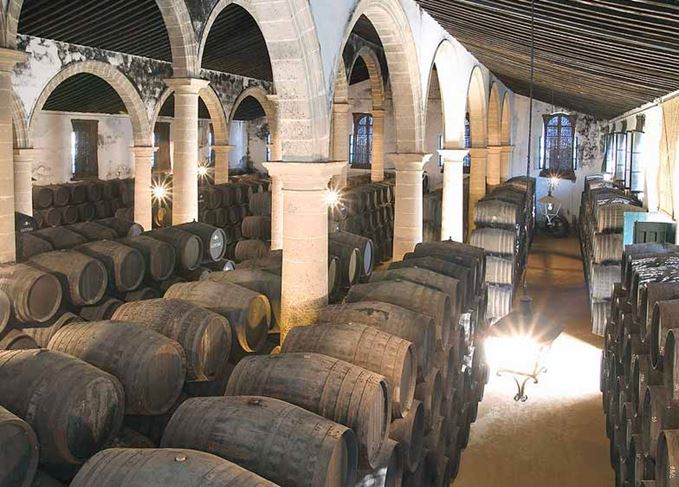

Special ingredient: The Whisky Professor reveals all about this not-so-secret seasoning

Dear Rosie,

You are quite correct that the use of paxarette (or ‘pax’ as it was commonly called) is now banned, but fear not: its prohibition had nothing to do with health. Its story is an intriguing one, which touches on the early use of Sherry casks, and 19th-century rejuvenation techniques.

First things first: what is it?

Paxarette originally hailed from a small region close to Jerez which specialised in sweet wines, before turning its production to the making of a style known as vino de color. This is used as a sweetening and colouring agent in the blending of sweet Sherry styles, such as Old East India or Brown.

Vino de color is produced by adding concentrated grape must to fermenting grape juice. The resulting wine, which only reaches around 8% abv, is fortified and then aged in solera. A number of different styles are made, varying in terms of concentration.

Paxarette is made by adding the vino de color to a blend of oloroso, Pedro Ximénez and wine must. This can then be further fortified to around 20% abv. I have tasted it – its production is not banned – and it has a not wholly unpleasant, slightly treacly, somewhat caramelised/burnt, raisin-like character. Think of it as a Spanish version of Buckfast.

Why, though, was it used in Scotch?

Rise and fall: Pax arose during the decline of Sherry consumption in Scotland in the 1800s

It has been believed that Sherry casks were widely used by the emerging Scotch industry in the 19th century because of the surfeit of butts on the docksides. Scotland drank a lot of Sherry; therefore there were empty casks and the industry used them – or so goes the argument.

The reality is slightly different. Sherry consumption in Scotland actually fell towards the end of the 19th century, meaning there was a shortage of casks. While blending houses continued to use a wide variety of cask types – rum and wine were popular – Sherry had become the most highly regarded in terms of flavour delivery.

A solution was therefore needed. Enter WP Lowrie, ‘King of the Blenders’. Based in Glasgow, Lowrie was the long-standing agent for leading Sherry producer González Byass, and a man who knew his Sherry. If he couldn’t get casks, then no-one could. Lowrie’s solution to the problem was a clever one.

He entered into an arrangement with American cooperages to supply staves and ship them to his warehouse in Glasgow, where they were assembled into casks and then seasoned in order to create a new type of ‘Sherry cask’.

While it is unclear what specifically he employed for this seasoning process, the use of paxarette for this purpose soon became common practice across the industry. Indeed, Diageo (which absorbed Lowrie’s firm in its DCL days) still maintains a ‘bodega’ in Carsebridge, where it rejuvenates its fortified wine casks.

Adding paxarette became a default activity, and all distilleries or disgorging plants would have a cask of it to hand. Every time a Sherry butt, or sometimes hogshead, was emptied, the colour of the whisky would be checked and, if it was believed that the cask needed a bit of a boost before the next fill, some pax would be added, either by the cupful or, in some cases, injected with compressed air.

Replenish stocks: Paxarette was added to tired Sherry casks to revitalise them

It would not just rejuvenate casks, but was used to give a boost to the flavour of ex-solera casks made from exhausted oak, which were entering the system.

There are even accounts of queues of Speyside housewives waiting at distilleries in the festive season for a cupful of pax to use as the (not so) secret ingredient in their Christmas puddings.

All of this changed in 1990, when the Scotch Whisky Order was revised. Paxarette was deemed to be an additive which affected the flavour of the whisky, and was therefore banned.

It leads me to wonder how much of the flavour of pre-1990 ‘Sherry cask’ whiskies was actually paxarette-driven, rather than Sherry- (or oak-) derived.

Your question has also prompted me to wonder whether, given the recent relaxation of laws over the use of cask types, whether a cask from a paxarette solera might now be permitted.

I think I might just write to the Scotch Whisky Association and ask.

With many thanks,

Prof

Do you have a burning question about Scotch whisky for the Whisky Professor? Email him at [email protected].