Perhaps best-known for Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Truman Capote was a supremely talented writer who pioneered the new literary genre of ‘faction’. He was also flamboyant, unpredictable and a huge lover of J&B Rare. Iain Russell tells his story.

Nobody would label Truman Capote (1924-84) as a typical American.

The extravagantly talented writer was just 5ft 2ins tall and dressed in his own flamboyant and highly personal style. He became famous for his catty and often indiscreet pronouncements, delivered to gatherings of his wealthy celebrity friends and on television talk shows in the same child-like, lisping Southern whine.

And, even in the 1950s and 1960s, when the merest media hint of homosexuality could ruin the career of a public figure, he made no attempt to hide the fact that he was a gay man.

But this unique character, the author of Breakfast at Tiffany’s and a pioneer of the literary genre sometimes called ‘faction’, had one thing in common with millions of his fellow Americans: a fondness for Scotch whisky and particularly for the most fashionable brand of the day, J&B Rare.

Christened Truman Streckfus Persons, Capote was born in New Orleans and raised in Alabama. He moved to New York City in 1934 with his mother and the stepfather who gave him his new surname.

By his own account (and he was prone to invention and exaggeration), he started writing at night at the tender age of 10 (or was it 15?). It excited him so much that he could not get to sleep afterwards without a few swigs of whisky.

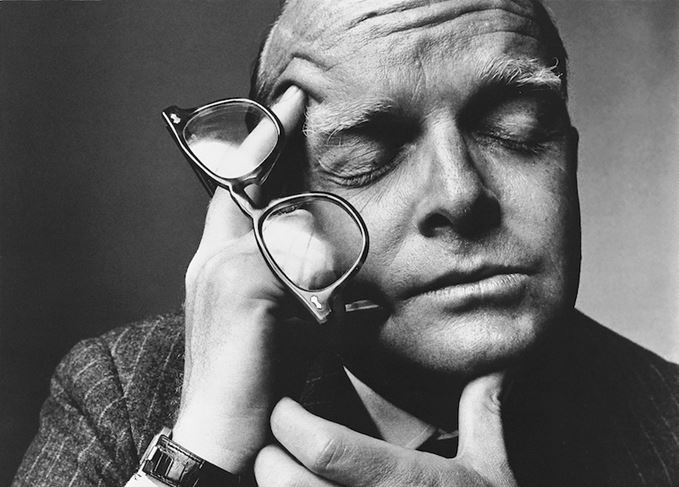

Young man: Capote claimed to have started night-time writing sessions at the age of 10

Capote began writing short stories, finding an appreciative readership at Harper’s Bazaar. His first novel was published in 1948 and he established his reputation as one of the most exciting authors in post-war America after the publication of Breakfast at Tiffany’s in 1958.

In 1959, Capote started work on what became In Cold Blood, the trailblazing ‘nonfiction novel’ based on the story of two killers and the family they brutally murdered in a small town in rural Kansas. He made numerous visits to the area to research the story, often accompanied by his childhood friend, future Pulitzer Prize winner and Scotch whisky aficionado Harper Lee.

A lawyer representing the estate of the murdered family remembered many years later that Capote and Lee came to his house for Christmas dinner: ‘Truman always brought along his bottle of J&B Scotch… I know he did it when he visited other people’s houses. After he became known here and various people started having parties for him, it greatly increased the sale of J&B Scotch.’

The light, smooth style of J&B Rare had captured the imagination of American Scotch drinkers in the 1950s, assisted by its identification as the drink of choice for popular stars such as singer Dean Martin and comedian Jackie Gleason.

Americans were buying one million cases a year of J&B Rare by 1963. But what probably appealed most to Capote about the whisky was its name – or rather, the name that he chose to call it.

J&B man: Capote was one of several high-profile American fans of the blend

Capote was one of America’s greatest social climbers, drawn like a magnet to the rich and famous, the titled and privileged. Justerini & Brooks, the London-based owner of the J&B brand, had been purveyor of fine wines and spirits to the British Royal Family and aristocracy since 1760. That was just the sort of brand to attract the snob in Capote.

According to legend, Capote would never ask in a liquor store for a bottle of ‘J&B’, the name by which the whisky was known to most American drinkers. Instead, he demanded a ‘Justerini and Brooks’. If the storekeeper didn’t know what he was talking about, he would roll his eyes and walk away to purchase his favourite Scotch elsewhere.

Whisky became a key part of Capote’s daily life. He believed that drinking and smoking were an integral part of his writing process. ‘I’ve got to be puffing and sipping,’ he claimed.

‘As the afternoon wears on, I shift from coffee to mint tea to Sherry to Martinis.’ But after he stopped work he often moved onto Scotch, continuing his habit of taking a bottle to parties and dinners with Manhattan’s ‘it crowd’.

In 1966, Capote organised his legendary Black and White Ball at Manhattan’s Plaza Hotel. Only the most wealthy, the most talented and the most powerful figures in the US were invited, and it established his reputation as the man with the best connections to America’s social elite.

But he was already struggling as a writer to match the critical and popular success of In Cold Blood and, perhaps distracted by his media celebrity and constant demands for newspaper interviews and talk show appearances, he published less and began to drink more.

Burn bright: Capote never recaptured the heights of his ‘faction’ novel, In Cold Blood

In 1975, Capote released passages from a novel he had been writing, based on gossip and shocking true-life tales about the secrets and foibles of his wealthy socialite friends. He was immediately ostracised by all but a very few of the jet set. His drinking and drug-taking increased.

Lee Radziwill, Jackie Kennedy’s sister, went on vacation with him to New Orleans. ‘He’d sit around with his Scotches and talk late into the evening,’ she remembered.

He also carried a little doctor’s bag stuffed with prescription pills for his many real and imagined ailments, and offered to share them with his companion. ‘This is gonna make you feel fantastic, hon,’ he told her. ‘Take it with a little Scotch and you’ll feel great in the morning.’

During his later years, Capote appears to have abandoned whisky and Martinis in favour of ‘my orange drink’ – vodka screwdrivers. Friends noticed that he would also lace grapefruit juice, 7-Up and other soft drinks with large shots of the virtually odourless spirit.

Capote began to spend a lot of time at the infamous Studio 54 and some of the seedier Manhattan nightclubs, indulging heavily in cocaine and other recreational drugs while continuing to drink heavily.

He died in 1984 of liver cancer and other conditions associated with drug and alcohol abuse.

Capote was famous for bons mots and self-promoting asides, any one of which might serve as his epitaph. But perhaps the most succinct, if neither the most humorous nor the most humble, was this statement: ‘I’m an alcoholic. I’m a drug addict. I’m homosexual. I’m a genius.’

Perhaps if he had just stuck to Scotch and Martinis, he might have left us with more evidence of that genius.