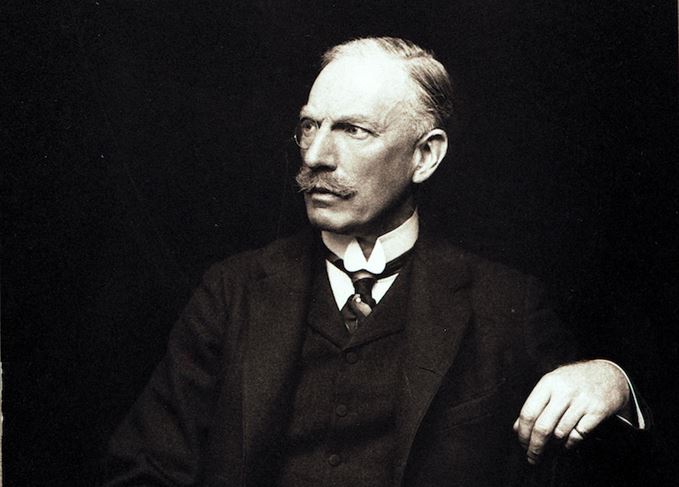

Fiery blended whisky pioneer and staunch Scottish Unionist, ‘Restless Peter’ Mackie took on all-comers, from distillery rivals to Liberal Chancellors. Gavin D Smith tells the tale of one of the leading figures of the early 20th-century Scotch whisky industry.

‘One-third genius, one-third megalomaniac and one-third eccentric.’

So wrote author, diplomat and secret agent Sir Robert Bruce-Lockhart about one of the true pioneers of blended Scotch whisky, a man nicknamed ‘Restless Peter’ by his contemporaries. His real name was Peter Jeffrey Mackie.

Mackie was born on 26 November 1855 in St Ninians, near Stirling, the son of a farmer and grain merchant, Alexander Mackie.

At the age of 23, he started work for his uncle, James Logan Mackie, whose Glasgow-based whisky firm Mackie & Co had been established the year after Peter’s birth.

Mackie worked in partnership with John Graham, whose family leased the Islay distillery of Lagavulin, and Peter was immediately sent there to learn the art of distillation. This gave him an invaluable practical knowledge of the whisky industry.

The Mackies began to blend whisky during the mid-1880s, with Lagavulin at its heart, and Peter Mackie registered the ‘White Horse’ brand in 1891, a year after Mackie & Co (Distillers) was established, with Peter as a partner.

The name White Horse was chosen because of the Mackie family’s centuries-long association with the famous White Horse coaching Inn, situated on Edinburgh’s Canongate.

In 1895 Mackie’s became a limited company, with Peter as chairman, by which time the White Horse blend was enjoying success in a number of export markets, and the firm decided it needed to become involved in distillery ownership in order to secure a supply of malt spirit.

Accordingly, Mackie’s became one of the partners in the Craigellachie Distillery Co Ltd, which in 1891 constructed Craigellachie distillery on Speyside. Mackie & Co (Distillers) Ltd went on to take full control of Craigellachie during 1916.

Peter Mackie had a large sign in his office at 13 Carlton Place, Glasgow, bearing the legend Take nothing for granted, and he was described by Allen Andrews in his 1977 book The Whisky Barons as ‘The fieriest of all the modern pioneers of blended Scotch whisky…’

This temperament was well illustrated by the creation of Malt Mill distillery in 1908 and by his response to Liberal Chancellor David Lloyd George’s Budget the following year.

As well as his association with Lagavulin, Peter Mackie also acted as sales agent for nearby Laphroaig distillery. When he lost this role due to a disagreement over water rights, he decided to make his own version of Laphroaig.

Accordingly, he constructed a small distillery named Malt Mill within the Lagavulin site, poaching Laphroaig staff to run it for him and firing the stills using only peat. Despite never proving a danger to Laphroaig’s sales, Malt Mill continued to operate until 1960.

Peter Mackie’s next battle was waged against Lloyd George. Mackie was a staunch Tory who was outraged by the ‘People’s Budget’ of April 1909. The provisions included an increase in distillers’ licence fees and in duty on spirits by 3s 6d, from 11s to 14s 6d. This was a rise of approximately one-third, and all Scotch whisky distillers were predictably furious.

Peter Mackie provided the most memorable response to the Budget when he declared that:

‘The whole framing of the Budget is that of a faddist and a crank and not a statesman. But what can one expect of a Welsh country solicitor being placed, without any commercial training, as Chancellor of the Exchequer in a large country like this?’

When it came to blending whisky, Peter Mackie was passionate about quality, using significant amounts of well-aged component malt whiskies, and he campaigned for a minimum age specification for Scotch whisky.

Successful blend: White Horse took its name from an Edinburgh coaching inn

The distillery chronicler Alfred Barnard was commissioned by Mackie to produce a pamphlet about the company’s distilleries and blending operations, and the chapter entitled How to blend whisky is revealing of Mackie’s modus operandi.

Barnard writes:

‘By request we give an example of a blend that has been most popular both at home and abroad. Average age, seven years.’

This is presumably White Horse, and Barnard describes the composition – with only one-quarter grain whisky – as follows:

3 Glenlivets_____________5 parts

2 Islays_________________3 “

2 Lowland Malts_________3 “

1 Campbeltown__________1 “

2 Grains________________4 “

-----

16

Although whisky was his abiding passion, ‘Restless Peter’ Mackie managed to find time to involve himself in a wide variety of interests, including the manufacture of BBM – ‘Bran, Bone and Muscle’ flour – which was prepared in the basement of the firm’s Glasgow premises, with all company employees being instructed to buy it for baking purposes.

As an active and vocal member of the Scottish Unionist Association, he wrote and spoke extensively about tariff reform and federalism, travelling widely in the process.

He was also an estate owner in Argyllshire, donating cattle from his own herd to Rhodesia in 1918 in order to encourage livestock breeding there. He even financed an anthropological expedition to Uganda.

Mackie was created a baronet in the 1920 Birthday Honours, and in the same year Mackie & Co (Distillers) Ltd acquired Hazelburn distillery in Campbeltown.

When in the ensuing years Campbeltown whiskies began to gain an unwelcome reputation for poor quality, Mackie announced that his Hazelburn distillery was no longer producing Campbeltown whisky – but Kintyre whisky.

It is said that Sir Peter Mackie was amenable to the sale of his company in the early 1920s, partly because his son and likely successor had been killed during the First World War. Unsuccessful negotiations were held with John Dewar & Sons, prior to Mackie’s death in September 1924 at Corraith in Ayrshire.

In that year the firm was renamed White Horse Distillers Ltd and became a public company, ultimately being taken over by the mighty Distillers Company Ltd (DCL) three years later.

DCL – and its successor company Diageo – continued to develop the White Horse brand, which now sells principally in Japan, Brazil, Greece, the UK, Africa and the US.

It still boasts a relatively high malt content and has a peaty character redolent of Lagavulin – a fitting legacy for one of the whisky industry’s most energetic and committed figures.