In the history of Ardbeg and Islay whisky, the figure of Colin Hay looms large. Not only did he bring the distillery back from the brink of destruction, he is credited with ushering in the most prosperous period in its history. Iain Russell tells his story.

The history of Ardbeg distillery is one of long periods of prosperity, punctuated by depths of despair and closure. Colin Hay (1827-99), one of the most important figures in the story of Islay whisky, emerged from just such a period of crisis.

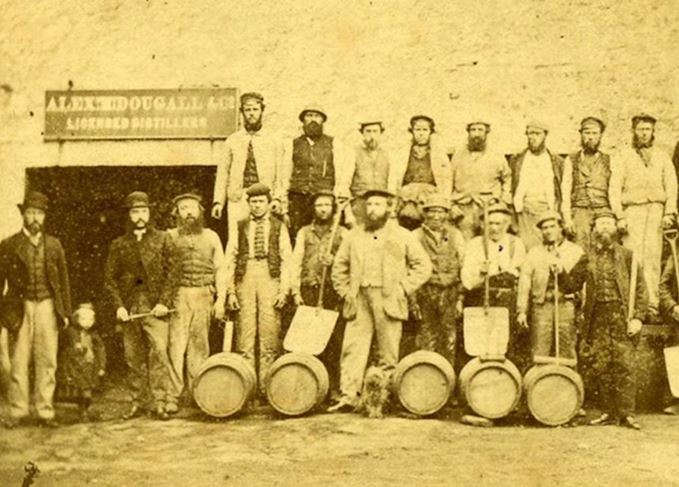

Hay was a native Ileach, born in Kildalton Parish, who began work at the distillery in the 1840s. The business was managed by Alexander McDougall, the resident partner in Alexander McDougall & Co, but all was not well.

An Excise officer reported in 1846 that McDougall ‘is paralytic and constantly confined to his chair [and] consequently not able to look after his affairs’. The exciseman believed that distillery workers were taking advantage of his incapacity, stealing new make spirit from the worm and carrying it off for their own consumption.

McDougall’s sisters Margaret and Flora had to take on much of the responsibility for running the business, appointing Hay as their manager, but they struggled to keep the business going after their brother’s death in 1853. When Ardbeg’s agents and major creditors, Buchanan, Wilson & Co., examined the books after Flora’s death in 1857, they were horrified by what they found.

Customers had been removing casks without any record of payments to their accounts. Lawyers’ fees had been paid in whisky from the warehouse rather than in cash, leaving a gaping hole in the company’s own stocks.

As it was: Ardbeg’s stillhouse in about 1900, depicted by a local artist (Photo: The Museum of Islay Life)

At the same time, lavish personal expenses had been put through the company’s books, including an intriguing bill for providing ‘outfits and a passage to India’ for Alexander’s late brother and distillery manager, Dugald. None of the debts appeared to be recoverable.

As they had done in 1838, when the Ardbeg distillery was last threatened with closure, Buchanan, Wilson & Co stepped in to provide a financial rescue package. And the man they chose to lead the recovery was Colin Hay.

The manager had become Margaret’s partner in the business in the 1850s, and sole partner after Margaret’s death in 1865. Hugely indebted to Buchanan, Wilson & Co to begin with, he took Alexander Buchanan into partnership in Alexander McDougall & Co in 1872, swapping the debt for equity. Ardbeg’s future was secured – for now at least.

Ardbeg’s whisky was in great demand from blenders in the mid-19th century. It was also supplied to wine and spirits merchants across the UK for sale as a single malt, and exported to the US, Argentina, Australia and New Zealand. It was ‘decidedly the best whisky made in Scotland’, proclaimed one merchant’s advert. A New Zealand hotelkeeper called it ‘The Ticket for Scotchmen’.

Hay worked tirelessly to develop the business. He installed larger stills to increase production capacity and erected new warehouses to store growing stocks of maturing whisky.

He built a new deep-water quay to land coal, barley and other essential supplies on the distillery’s doorstep, and to ship whisky more quickly and cheaply to the mainland. In 1883 he installed a steam engine at the distillery, when the water wheel alone could no longer supply the power required for new machinery.

Shipping casks: Distillery manager Alexander Campbell supervises proceedings at Ardbeg’s quay (c.1912)

Journalist Alfred Barnard noted that production had risen to 250,000 gallons of whisky per annum by 1886 – 25 times the amount distilled annually in the 1820s. There were 60 men employed at the distillery at that time, and the small village of Ardbeg had grown to about 200 people, with its own school for the children of the village and surrounding area.

By then, Hay had built a magnificent house on the seafront next to Warehouse No 3. He laid out a beautiful garden on the hillside to the west of the village, and built a large greenhouse to grow fruit and vegetables. A well-appointed billiards room was provided for the men to pass their leisure time, and wives and children could join them for special events in the evenings.

Hay was a pillar of Islay society. He was a farmer of nearly 2,300 acres, on which he raised cattle, as well as sheep. He was also a Justice of the Peace, a parish councillor and a driving force of the Glasgow Islay Association. A passionate supporter of Gaelic education, he championed the revival of Gaelic literary traditions.

Ardbeg survived the depression in the market for Islay whiskies of the late 1880s and early 1890s. It survived, too, the huge fire of December 1887 which destroyed the stillhouse, tun room, malt barns and kiln. When Hay retired in 1897, the distillery was reputedly the largest and most successful on the island.

New century: Ardbeg in the early 1900s. Colin Elliot Hay is believed to be on the left, holding the keys

Hay hoped, but failed, to establish a dynasty at Ardbeg. His eldest son Alexander was his chosen successor, but died in 1896. A second son, Robert, was described by Hay himself as a ‘a soft-headed young fellow’ who ran away to work on a sheep farm and hunt rabbits in New Zealand. He died soon after finally obeying his father’s demand to return home.

A third son, Colin Elliot Hay, returned from the mainland as manager after Alexander Hay’s death, and he became the resident partner and one of the leading shareholders in Alexander McDougall & Co.

The son tried hard to emulate his father, who had criticised him for exhibiting ‘no moral strength or courage to break off from evil companionship’ when he was a young man living on the mainland.

There were rumours in the village that he drank too much, and he became unpopular. He left Islay after the First World War, returning only rarely, and died with crippling debts in 1928.

Successive management teams had to deal with many new crises at the distillery after the departure of the Hays. It closed during the Depression of the early 1930s. It was closed again from 1981 until 1989, and then in 1996, before reopening in 1997 under current owner The Glenmorangie Company.

Much of Ardbeg’s resilience can be put down to the work of Colin Hay, who turned a troubled business around, built a solid reputation for the whisky and laid the foundations of a ‘brand’ that is one of the best-known in Scotland today.