Immortalised on every label of Glen Grant, brothers John and James Grant were quick to adapt when Scotch whisky went legit in the 19th century, moving seamlessly from smuggling to entrepreneurship. Iain Russell tells their story.

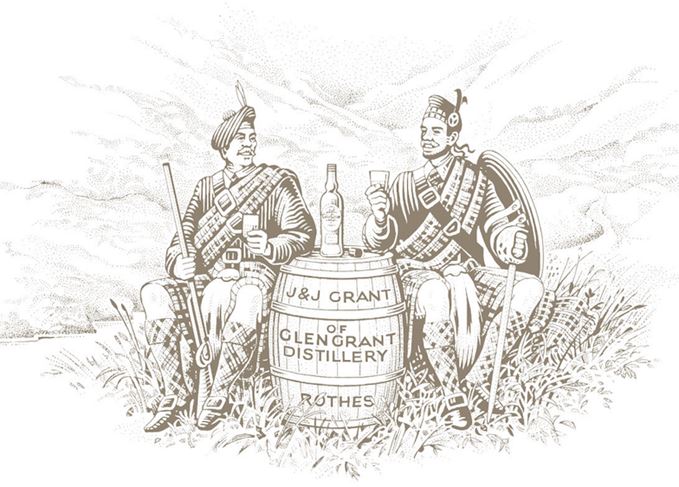

Since the mid-19th century, the label on every bottle of Glen Grant has featured two plaid-clad Highlanders, sitting by a cask and sharing a dram.

The men are the brothers John and James Grant, who founded the distillery. One of them was a whisky smuggler-turned-distiller who developed an international market for Glen Grant.

The other was a politician who marched in the last clan rising in Scottish history, and delivered a sound thrashing to a pair of garrotters…

Family business: the Grants' distillery is now owned by Italy's Campari

The Grants were born in Shenval in Morinsh, not far from George Smith’s birthplace at Upper Drumin in Glenlivet.

John (1797-1864) became a grain dealer, but there wasn’t a lot of grain to deal in: it was a well-known fact that there were hundreds of illicit stills working in the area, and most of the local barley crop was distilled into whisky.

So John’s stated profession was really just a cover – in fact, as his contemporaries remembered later, he made his living as a whisky smuggler.

John bought illicit whisky from his neighbours and sent it south across the hills, in casks slung across the backs of sturdy ponies. He sold it to customers in Perth, Dundee and the small towns along the way, and he was instrumental in establishing the enormous popularity of smuggled ‘Real Glenlivet’ whisky.

When the Excise authorities clamped down on illicit distilling in the 1820s, and the first licensed distilleries were founded in Glenlivet, he began dealing in ‘legal’ whisky instead.

John’s main client was his friend George Smith. At first, he had problems persuading his customers to buy the produce of a licensed still – the harsh, fiery whisky produced by the ‘entered’ lowland distillers had given legal whisky a bad reputation among whisky aficionados of the day.

So he cunningly informed them that Smith’s Glenlivet was smuggled whisky, only letting them know the truth once they’d tried it and developed a taste for it.

Grant was soon buying 200 gallons of Smith’s Glenlivet a week. It wasn’t long before he had thoughts about making whisky too.

John’s brother James trained as a solicitor in Edinburgh and, after qualifying, set up in business in Elgin. In 1834, he and his brother went into business with two Elgin drapers, taking over the lease of the Aberlour distillery. Knowing that the lease expired in 1840, the brothers made plans to set up on their own.

According to legend, John took expert advice on brewing and distilling techniques from George Smith, then sat down by a hazel bush on the bank of the Back Burn in Rothes, and sketched plans for his distillery in the hollow.

The distillery was named Glen Grant, and opened in 1840 with John in sole charge of the distillery’s management. It was an instant success.

Whisky brethren: the Grants' likeness still adorns every bottle of Glen Grant

There are authors who insist that single malt whisky did not reach a wide audience in Victorian times, and that whisky blenders were the first to develop overseas markets. They clearly haven’t looked at the story of Glen Grant.

The brothers began distilling 1,500 gallons of their ‘Glengrant Glenlivat whisky’ each week, and sent a large proportion to their own warehouse in London.

The whisky was intended for drinking as a single malt: when they discovered that their agent there ‘increased the sales of plain malt spirits raw grain and other inferior sorts of whisky by mixing them with the pure malt whisky manufactured by the firm of J&J Grant’, they ended his agency agreement.

And Glen Grant sales were not confined to the British Isles – according to John himself, speaking in 1854, ‘the produce of the distillery of Glengrant… found its way direct from the distillery to North and South America, Sierra Leone, Gibraltar, the Cape of Good Hope, Bombay, Calcutta, 500 miles up the Ganges, Canton, Hong Kong and Australia’.

And what of his wee brother James? Well, James was the silent partner in Glen Grant, but he had a pretty eventful life himself. In 1820 he marched on the Raid on Elgin, the last clan raid in Scottish history, when the Grants travelled en masse to Elgin to rescue their Clan Chief’s family from a mob that had besieged their home there.

He later became Provost of Elgin, and one of the great railway promoters who provided Speyside with the modern transport links required to stimulate the whisky industry there.

John and James were major shareholders in the Morayshire Railway Company, James was chairman, and one of the steam engines which worked the line was named Glen Grant in their honour.

James’ winning personality, after he had danced and sung his way through his speech to an audience of 1,700 employees and their partners at a Great North of Scotland Railway Company function, prompted a journalist to write in the Forres Gazette that ‘the man’s a marvel, sir, a marvel of pluck, spirit, and honest outspokenness’.

And as for the garrotters…

In the 1860s, James visited London on business. Two ruffians ambushed him as he walked across Trafalgar Square one evening, one wrapping a knotted rope around his neck to garrot him – intent on squeezing until the unfortunate victim blacked out – and the other rifling his pockets.

As he fell to the ground they ran off with his gold watch and chain, but the Provost was made of stern stuff. He got to his feet and gave chase, knocking down one of his assailants with his stick, and then giving the other a sound thrashing when he turned back to help his accomplice.

The police arrived, he retrieved his valuables, and the battered garrotters were taken off into custody.