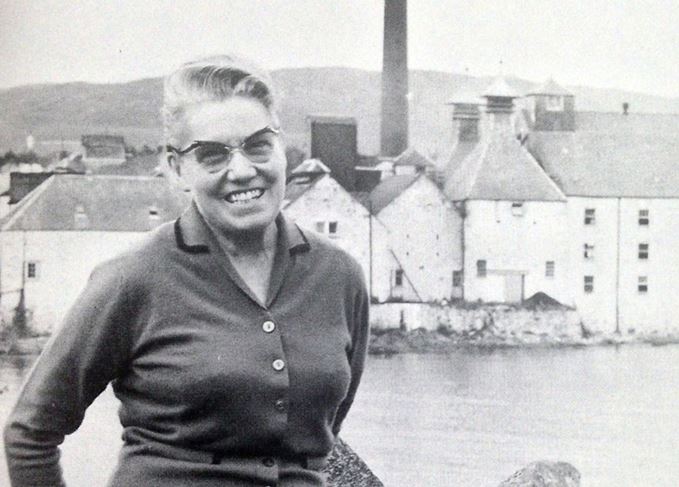

Bessie Williamson, whose name will always be indelibly linked to Laphroaig, was, in the words of one news report, a ‘woman of spirit’ – the only female to own and run a Scottish distillery in the 20th century. Iain Russell tells her story.

Bessie Williamson (1910-82) wasn’t from Islay. She had no family connections with the whisky business. And she lived in an era when women were rarely employed in Scotland’s distilleries, other than as office clerks, secretaries or cleaners.

Yet Bessie is a legendary figure in the history of Islay’s whisky industry. She became managing director of the Laphroaig distillery on Islay and was the only woman to own and manage a distillery in Scotland in the 20th century. How did that happen?

Elizabeth Leitch Williamson was born in Glasgow’s High Street, the daughter of an office clerk who was killed fighting with the British Army in France in 1918. His widow was left to raise Bessie, her sister and brother alone.

Bessie matriculated at the University of Glasgow in 1927. She studied for a general Arts degree, but she had to re-sit several exams and it took her five years to complete the three-year course.

Her uncle found her a job working for a restaurant company so that she could earn some money to help pay her way through teacher training college, and Bessie attended night classes to learn useful secretarial and clerical skills.

With her best friend Margaret Prentice, Bessie went to Islay on holiday in the summer of 1934. She learned of a temporary vacancy for a shorthand typist at the Laphroaig distillery and her application was successful. She never went back to teaching.

Laphroaig belonged to D Johnston & Co, a company owned since 1927 by Ian Hunter (1886-1954). Hunter had a reputation for irascibility, but he seems to have taken a shine to Bessie. He asked her to manage the office at Laphroaig and she became his most trusted lieutenant.

Making her mark: Bessie became a trusted employee at D Johnston & Co

Iain Maclean, who worked at the distillery, told journalist Andrew Jefford:

‘She was nice, a very attractive girl… she was very clever, an educated woman.’

After Hunter suffered a stroke in 1938 and was confined to a wheelchair, Bessie took a greater share in the management of the business. In 1944, when the distillery was about to restart production after being used as a barracks and ammunition store during the Second World War, he transferred control to her. D Johnston & Co became a limited company in 1950, and Bessie was appointed company secretary with a small shareholding.

Hunter died in 1954; he left money to long-serving employees in his will, as well as £5,000, the distillery business, Ardenistiel House and the island of Texa to Bessie. She continued to entrust much of the day-to-day management of whisky production to Tom Anderson, the long-serving brewer, but kept charge of the company’s business affairs.

Iain Maclean approved of her management style:

‘She was a good boss. She just let the workers carry on with their work; it was the proper thing to do. Everybody knew his job anyway… She never had any bother.’

Laphroaig certainly flourished under her leadership. Like the other Islay distilleries, it focused on producing single malt for the large blending houses on the mainland, and she told a visiting documentary crew in the early 1960s that ‘we can’t supply the demand that we have for our whisky’.

Old times: Laphroaig's still house before reconstruction – work that was overseen by Bessie

Bessie’s sound business sense, allied no doubt to the curiosity value of being a woman in a very male business, certainly impressed the officials of the Scotch Whisky Association. The SWA invited her to tour North America in the 1960s, lecturing on Scotch whisky production. It was during one of these tours that she met the Canadian radio star Wishart Campbell.

Campbell (c1905-83) was the grandson of an Islay minister who had emigrated to Canada in the 19th century. The journalist John McPhee described him as ‘somewhat heavyset, but nonetheless athletic in carriage, a glib man, quick, fluid, idiomatic’. He was an accomplished pianist and baritone, and was known as ‘The Golden Voice of the Air’. There was a whirlwind romance and he and Bessie married in Glasgow in 1961.

Bessie was widely respected on Islay for her contribution to the island’s social as well as its business life. She played a prominent role in the Scottish Women’s Rural Institute, organising concerts, fêtes and tea parties to raise money for worthy local causes: the Kildalton branch, which she chaired, met in the community hall at the distillery. In 1963, she was awarded the Order of St John for her charity work.

In contrast, Wishart was unpopular with many islanders, who suspected him of being a gold-digger. They say he arrived on Islay with his new bride bringing nothing more than a suitcase and a white grand piano.

But he and Bessie (whom he referred to as ‘Mrs C’) seem to have been a happy couple. They lived at Ardenistiel and Wishart started a small market-gardening business, selling his fruit, vegetables and flowers to local businesses.

He was willing to play his part in promoting the whisky to visiting journalists – he suggested Laphroaig was the liquid equivalent of George Gershwin’s Love Walked In with the bass turned up to the max – but continued to favour rum and Pepsi as his tipple of choice.

A Woman of Spirit: Bessie features in this classic Movietone News clip from 1964

Laphroaig may have been one of Islay’s most in-demand whiskies, but Bessie realised it required substantial investment to modernise production facilities and increase warehousing capacity. She approached local landowners the McTaggart family with an offer to sell them the distillery for just £80,000: the McTaggarts owned one of Scotland’s leading construction companies and had the deep pockets required for long-term investment projects.

When the family declined her offer, she came to an agreement instead with the American-owned Long John Distillers. They acquired the share capital in the distillery company from Bessie in three instalments, in 1962, 1967 and 1972.

Bessie remaining as chairman and managing director of D Johnston & Co Ltd, with a seat on parent company Long John’s board, until she retired in 1972. She was at the helm when the new still house was built in 1967, with steam heating in place of direct coal fires for the stills, and other construction and modernisation programmes begun. However, her last years at the distillery were inevitably uncomfortable, as the mainland company strove to modernise working practices at the distillery.

According to John McDougall, who worked briefly with Bessie when he became manager in 1970, Laphroaig had become known locally as the ‘Islay Labour Exchange’ because Bessie ‘could not listen to a hard luck story without giving in and providing a job for the person concerned, even though there was usually no job at all’.

Bessie herself informed her fellow board members at Long John that she had kept on many of the older employees because ‘we have no pension scheme’. Inevitably, there were redundancies among the workforce after Bessie handed over full control to Long John, but her achievement in guiding the distillery through difficult times and maintaining the high reputation of the whisky, while creating employment for so many local men, was greatly appreciated locally.

And what of her legacy? An AP news presenter sums it up nicely (if perhaps unintentionally!) in a 1964 report:

‘You’d expect [whisky] production to be an entirely male preserve. Mrs Campbell proves you wrong.’

Her greatest achievement was to win widespread recognition for her success in business, in what was one of Britain’s most traditional and male-dominated industries, and to prove, once and for all, that it was wrong to suggest that whisky making was just ‘man’s work’.