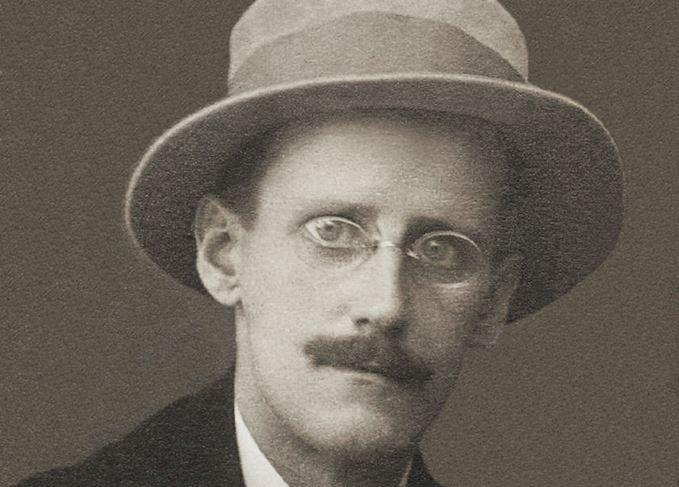

James Joyce was a loyal lover of Jameson, but his links with Irish whiskey run far deeper into his family history. In the run-up to the Bloomsday celebrations on 16 June – marking the date on which Joyce’s Ulysses is set – Richard Woodard investigates the life and work of the man widely hailed as Ireland’s greatest writer.

James Joyce (1882-1941) is best remembered as the author of highly original and densely written books such as Ulysses, Dubliners, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and the notoriously impenetrable Finnegans Wake.

Dublin-born, Joyce spent much of his life in mainland Europe, but his works are suffused with the city’s scenes and characters, many of the latter loosely based on friends and family, acquaintances and enemies. He is famed for his neologisms or invented words, his stream-of-consciousness style and the multiplicity of meanings that can be attributed to his writing.

With Joyce, rarely is anything quite as simple as it first appears, and this applies to the author’s use of whiskey- and distillery-related themes in his works.

Even Joyce’s love of whiskey is open to question. He didn’t drink at all as a young man and, during the years he spent in Trieste, Rome, Zurich and Paris, was fonder of wine than spirits. Joyce especially loved white wine – ‘electricity’, he called it – but abhorred red (‘beefsteak’), singling out for particular praise an obscure Swiss white wine, Fendant de Sion.

Whatever his feelings for whiskey in general, there is no doubting Joyce’s loyalty to Jameson. He is said to have had ‘JJ’ in the Jameson typeface engraved in his wallet, and semi-cryptic allusions to the Jameson name litter Finnegans Wake: ‘Jhem or Shen’, ‘Jhon Jhamieson and Song’, ‘Juan Jaimesan’, and so on.

Phoenix Park: James Joyce’s father worked at the plant’s forerunner (Photo: Diageo Archive)

Despairing that he might never finish the work – Finnegans Wake took fully 17 years to complete – Joyce suggested in a letter to his publisher, Harriet Shaw Weaver, that Dublin poet James Stephens be approached to help with the task:

‘If he consented to maintain three or four points which I consider essential and I showed him the threads he could finish the design. JJ and S (the colloquial Irish for John Jameson and Son’s Dublin whisky [sic]) would be a nice lettering under the title.’

What was so special about Jameson that set it above its Dublin rivals of the time, including John Power, George Roe and William Jameson? Joyce had a ready explanation for fellow writer Gilbert Seldes:

‘All Irish whiskeys use the water of the Liffey; all but one filter it, but John Jameson’s uses it mud and all. That gives it its special quality.’

But whiskey for Joyce has a significance that runs far deeper than his love for Jameson and, for this most allusive and elusive of writers, it offers much more than mere liquid refreshment.

‘The light music of whisky falling into glasses,’ a phrase which occurs in Grace, one of the stories in Dubliners, is among Joyce’s most repeated quotes. But, as Prof Frank Shovlin of the University of Liverpool’s Institute of Irish Studies has pointed out, references to whiskey in the collection are mostly far from positive.

There is Cotter, the ‘tiresome old fool’ of The Sisters, with his ‘endless stories about the distillery’; and, in A Painful Case, the lonely figure of James Duffy:

‘He lived in an old sombre house and from his windows he could look into the disused distillery or upwards along the shallow river on which Dublin is built.’

Whiskey lover?: Joyce was more of a fan of white wine, which he called ‘electricity’

Meanwhile, in The Dead, the doomed Michael Furey sings to his love, Gretta, in a street called Nuns’ Island – also the name of a whiskey produced in Galway at a distillery once owned by a distant branch of the Joyce family.

Distilleries, breweries and their products (especially Jameson and Guinness) punctuate Finnegans Wake, which takes its title from a song in which Tim Finnegan is roused from his deathbed by whiskey. Uisce beatha (water of life) indeed.

The central figure of the book, Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker or HCE, suffers a series of misadventures, culminating, at the end of Part III, in the destruction of his distillery:

‘Till, ultimatehim, fell the crowning barleystraw, when an explosium of his distilleries deafadumped all his dry goods to his most favoured sinflute and dropped him, what remains of a heptark, leareyed and letterish, weeping worrybound on his bankrump.’

Whiskey, both as a drink and as a source of employment, was a prominent feature of Dublin in the late 19th century, but Joyce is doing more here than merely reflecting local life; in particular, he is recalling a painful episode from his own family history.

In 1874, Joyce’s father, John Joyce, was persuaded to invest £500 in an ambitious new business venture, the Dublin and Chapelizod distillery, located in a former convent, barracks and flax mill in Phoenix Park, in what was then the village of Chapelizod, a few miles from central Dublin.

Dublin and Chapelizod: The distillery was reopened and renamed by DCL (Photo: Diageo Archive)

The prospectus for the new business, later reprinted in the Distillers Company Limited’s DCL Gazette in 1923, is as lyrical as it is optimistic, highlighting the ‘practically unlimited’ demand for Irish whiskey, promising ‘a dividend of at least 25 per cent per annum’ for its shareholders, and adding for good measure:

‘Irish whiskey, there can be little doubt, will eventually, from its extreme purity and wholesome character as a stimulant, almost completely displace other stimulants such as Brandy, Rum and Gin.’

Like most things that look too good to be true, the Dublin and Chapelizod distillery turned out to be exactly that. John Joyce, appointed company secretary on a salary of £300 a year, lost his job and all his money when the company went into liquidation after operating for only three years.

It was only the first of a number of financial misadventures for John Joyce, which set his family on a descent from relative wealth into poverty – described by James Joyce in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, in which his father is referred to as ‘something in a distillery’.

The blame was laid squarely at the door of Henry Alleyn, the man who persuaded John Joyce to invest in the distillery, and who also wrote that lyrical prospectus. According to family legend, John Joyce discovered that Alleyn was embezzling from the firm and told his fellow shareholders, leading to Alleyn’s departure – but too late to save the business.

Convinced that his father had been wronged by Alleyn, Joyce created the character of ‘Mr Alleyne’ [sic] in Counterparts, another Dubliners story, a pompous and unpleasant boss who victimises the pathetic hero of the piece, Farrington.

The spectre of Chapelizod looms large in other Joyce works: a licensed premises in the village is the backdrop for Finnegans Wake, which has a reference to the ‘still that was mill’, and in which the central figure of HCE is undone by an allegation of impropriety in Phoenix Park.

Elusive and allusive: Whiskey has a multiplicity of meanings in Joyce’s works

Joyce’s coining of the word ‘finisky’ in the Wake appears to combine references to ‘whisky’, ‘finis (end)’, Phoenix and ‘fionn uisce (clear spring)’, from which Phoenix Park takes its name.

But is there more to this than recalling painful family memories and redressing perceived wrongs? With Joyce, a multiplicity of meanings comes as standard – and distilleries and whiskey can be seen to symbolise the plight of Ireland in the years before independence.

In Ulysses, a beer bottle abandoned on Sandymount beach symbolises the pernicious effects of alcohol on Ireland – ‘isle of dreadful thirst’, as Joyce calls it; and, as he wanders through Dublin, Leopold Bloom is fascinated by the rapid accumulation of wealth by those who make and sell alcohol – a phenomenon also referenced in Henry Alleyn’s distillery prospectus decades earlier.

If alcohol in 19th- and early 20th-century Ireland can be viewed as a means of subjugation – ‘Ireland sober, Ireland free’ was one Nationalist battle cry – that impression is only reinforced by the fact that most of the big distillers, John Power being an exception, were owned and controlled by Protestant families.

These families wielded considerable political power in Dublin and, as the ‘whiskey ring’, were stubborn obstacles to Nationalist political ambition. At one point, Andrew Jameson, fifth-generation owner of John Jameson & Son, was top of a Republican hit list of senators to be shot on sight.

Still that was mill: Phoenix Park is an especially important location in Finnegans Wake

The fate of the Dublin and Chapelizod distillery adds weight to this theory: shortly after its closure, it was acquired by the newly formed Scottish conglomerate, Distillers Company Limited (DCL) and renamed the Phoenix Park distillery.

What did Joyce make of this appropriation of his father’s doomed business venture by the British? And what did he think when Phoenix Park was swiftly mothballed (it was shut from 1893 to 1899), before reopening to make industrial alcohol until its final closure in 1921?

Joyce maintained a keen interest in the workings of the drinks industry, so we might also wonder how he reacted when the same DCL, reacting to the slump in whisky trade following the Pattison crash, embarked on its ‘slash and burn’ policy post-1902, buying up and then closing down distilleries on both sides of the Irish Sea. Such events would hardly encourage Joyce to paint whiskey and distillation in a positive light.

In the end, the question of whether James Joyce was an enthusiastic whiskey drinker becomes a sideline, a footnote to the subject’s broader significance in his written works. As Prof. Shovlin puts it:

‘Whiskey is, for Joyce, a complex and multilayered device by which he can achieve several results: by referencing it and stitching it into the weave of his fiction, he can gain revenge for his wronged father, [and] he can draw attention to the caste system of early 20th-century Ireland…’

In other words, whiskey is never ‘just’ whiskey for Joyce, but instead the subject acquires a personal, cultural and political resonance that transcends its status as a mere drink. But then, with a writer as complex and open to multiple interpretations as James Joyce, what else would you expect?