Dublin ruled the Victorian whisky world, but fell under the weight of a succession of reversals in fortune. Now, with Irish whiskey back from the brink and newly resurgent, the city is reclaiming its place in the spotlight. Richard Woodard reports.

The dry scribblings of Victorian whisky chronicler Alfred Barnard are hardly littered with hyperbole, but the author of The Whisky Distilleries of the United Kingdom becomes positively lyrical when he visits Dublin in the mid-1880s.

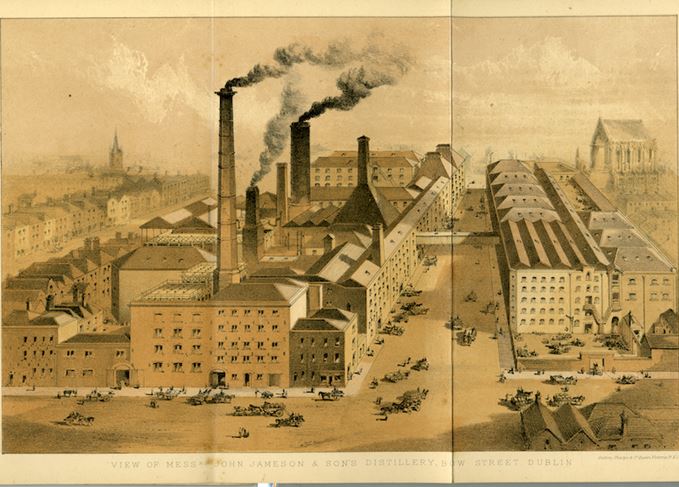

At John Jameson & Son’s Bow Street distillery, we read, ‘nearly every department has been supplied with new and improved machinery’, while the entrance to George Roe & Co’s vast Thomas Street plant is ‘unlike any other Distilleries we have seen, reminding us of some of the chateaux in France’.

The superlatives accumulate: William Jameson’s Marrowbone Lane distillery has ‘two mash tuns said to be the largest in the United Kingdom’; Phoenix Park, with its incandescent lighting and water-wheel spanning the Liffey, is the ‘most modern of any of the Distilleries owned by the Distillers’ Company, Limited [DCL]’.

Barnard reserves particular praise for Sir John Power & Son’s John’s Lane distillery, with its two 25,000-gallon wash stills, ‘said to be the largest Pot Stills ever made’, and a 20ft-long spirit safe that is ‘the most ingeniously-arranged one we have ever seen’.

‘The Distillery, altogether, is about as complete a work as it is possible to find anywhere,’ Barnard concludes, adding of the distillery’s ‘old make’: ‘It was as perfect in flavour, and as pronounced in the ancient aroma of Irish Whisky so dear to the hearts of connoisseurs, as one could possibly desire…’

None of this would have shocked Barnard’s readership. At the time of his tour, two out of every three bottles of whisky sold by London merchant Gilbeys were Irish, and the product of its 28 distilleries was a global success story.

Particular praise: Alfred Barnard rhapsodised about John Power’s distillery

‘It was a prestige product,’ says Irish Distillers archivist Carol Quinn. ‘If you had a cellar full of good Champagnes and Cognac, you had good Irish whiskey too. It was something you saved up for.’

For most connoisseurs, ‘good Irish whiskey’ meant Dublin. The second city of the British Empire, its rising population, port and numerous water sources had long made it a centre of distillation, but the Victorian era saw it reach the zenith of its influence and opulence.

Of the six Dublin distilleries visited by Barnard, ‘the big four’ – George Roe, John Power, John Jameson and William Jameson – were pre-eminent. Together, they had about 1,000 staff, produced roughly five million gallons of spirit a year, and covered a combined area of well over 40 acres.

‘These were vast complexes that employed a lot of people and were visible all around the city,’ says Jack Teeling, MD of Teeling Whiskey. ‘They had cooperages, bottling, and much more. Each of them was like a city.’

Their scale was underpinned by a conviction that the whiskey they produced was a class apart. ‘The Dublin distillers had a very firm belief that what they made was superior to what they would call “country whiskey”,’ says Quinn. ‘They were under the eye of the Revenue, a lot closer, they felt, than their country cousins… They felt they were being called to a higher standard.’

Like a city: Dublin’s vast distilleries housed all manner of trades (Photo: Irish Distillers)

In a further attempt to stand out, they began naming their product ‘City’ or ‘Parliament’ whiskey, dismissing rural rivals as ‘country’ – and always spelling whiskey with an ‘e’, in contrast to common practice at the time.

This was a great height from which to fall, but fall they did. Even the awe-filled descriptions of Barnard hint at darker times: Roe’s distillery, he writes, is capable of producing almost two million gallons of spirit a year, but he adds: ‘Like that of other Dublin distilleries, however, it has been reduced considerably during the past few seasons.’

Only a few years later, William Jameson and George Roe joined with the smaller Jones Road operation to form Dublin Whiskey Distillers (DWD), but all fell silent in the 1920s. Phoenix Park, the hugely ambitious foray into Irish whiskey of Scotch behemoth DCL, was reduced to producing industrial alcohol before the turn of the century, closing in 1921. And worse was to follow.

What happened? A complex mix of ill fortune, incompetence and geopolitical events, spearheaded by the advent of continuous distillation and the rise of grain whisky.

Contrary to popular belief, Irish distillers were not, initially at least, averse to the idea of the Coffey still. Within a decade of Aeneas Coffey being granted a patent for his apparatus, there were 13 of them operating in Ireland (compared to only two in Scotland), including one at John Jameson’s Bow Street distillery.

Keeping faith: In Truths About Whisky, Dublin’s distillers railed against grain spirit

‘They were used all over Ireland,’ says Quinn. ‘It was never the case that the Irish distillers were afraid of the technology, or didn’t embrace it. They did.’ But, she adds, there was a problem. ‘Their consumers didn’t like the product. They preferred the taste of the pot still.’

The anti-grain position hardened during the 1870s, when the Irish market was inundated with Coffey still spirit from Scotland and elsewhere, ‘teaspooned’ with small amounts of pot still and passed off as Irish whiskey.

This led to Truths About Whisky, a proselytising book published by Dublin’s ‘big four’ in 1878 that rails against the ‘silent spirit’ produced by Coffey stills. ‘As a matter of fact,’ it says, ‘these things no more yield Whisky than they yield wine or beer.’

What began as well-founded reluctance was fast becoming stubborn intransigence. Peter Mulryan writes in The Whiskeys of Ireland:

‘While their good names were being tarnished by counterfeit whiskey and their markets were flooded with cheap blends, the big four Dublin distillers sat immobile, convinced that the patent-still fad would pass.’

Jack Teeling adds: ‘The arrogance of success led to the demise of Irish distilleries. They were stuck in their ways, and they thought that was the only way to make whiskey.’

This sense of hubris punished has the compelling air of a Greek tragedy, but the full story defies such a simple explanation. In fact, Irish whiskey was buffeted by a series of blows over a period of several decades.

Big in America?: Irish brands like Jameson lost out to Scotch in the US (Photo: Irish Distillers)

The creation of bonded warehouses, with tax payable on shipment, facilitated the rise of the merchant blenders and, in Scotch, names such as Walker, Buchanan and Dewar; the brutal ‘slash and burn’ DCL policy of the early 1900s saw distilleries on both sides of the Irish Sea bought and wound up to protect the company’s market position.

Meanwhile, the pot still versus grain debate culminated in the landmark ‘What is whisky?’ case – the Royal Commission on Whiskey and Other Potable Spirits of 1908 – and defeat for the Irish cause.

There was conflict – not only two World Wars with trade embargoes, but the Easter Rising of 1916, when Bow Street became a rebel fortress; the War of Independence of 1919-21 and the subsequent Civil War.

The creation of the Irish Free State was a triumph for nationalism, but a disaster for distillers. If the 1800 Act of Union had opened up the lucrative markets of the British Empire to Irish whiskey, independence from London shut them back down again.

In the 1920s, as Prohibition hit the US, John Jameson and John Power were approached by patriotic Irish-American Joe Kennedy (father of John F Kennedy) to fulfil a ‘post-Prohibition’ order to supply whiskey; fearful of breaking US law, they demurred, leaving the Scots to fill the breach, and reap the rewards for decades afterwards.

By the early 1930s, as a costly trade war with the British began to bite, there were only five distilleries left in the Irish Free State, including two in Dublin – John Power and John Jameson – leading to DCL chairman William Ross’s infamous pronouncement: ‘Ireland is an irrelevance.’ In cold business terms, he was right.

Hanging on: By 1950, the Irish whiskey industry was ‘on its knees’ (Photo: Irish Distillers)

‘By the 1940s and 1950s, the Irish whiskey industry was on its knees, absolutely crippled,’ says Quinn. ‘Distillery after distillery was closing. It was clinging on by its fingernails.’

The contrasting wartime policies of London and Dublin didn’t help. While Winston Churchill ensured continuity of barley supply to protect Scotch, Eamon de Valera’s Irish Free State government capped whiskey exports, not once, but twice. ‘That,’ observes Quinn, ‘was the death-knell.’

In March 1966, as Irish whiskey seemed likely to vanish altogether, the three remaining companies – John Jameson & Son, John Power & Son and the Cork Distilleries Company – merged to form a new entity.

The United Distillers of Ireland (UDI) was swiftly renamed Irish Distillers Ltd (thanks to Rhodesia declaring its own UDI, or Unilateral Declaration of Independence, shortly afterwards), and soon the new body decided on radical action.

Production was to be consolidated at a new, IR£9m greenfield distillery in Midleton, County Cork. Dublin distilling, its vast plants rendered unfit for purpose by the modern city expanding around them, was now officially obsolete.

John Jameson’s Bow Street distillery fell silent in 1971; Powers in John’s Lane followed five years later. Irish whiskey was saved, but arguably its finest expression, Dublin whiskey, had been sacrificed in the process.

Jack Teeling was born in 1976, the year Powers closed. His family is a thread connecting Irish whiskey’s past to its present, from Walter Teeling setting up a small distillery in Marrowbone Lane in 1782, to his father John Teeling’s Cooley operation offering the first flickering signs of recovery from 1989.

New start: Whiskey-making returned to Dublin when Teeling opened its distillery in 2015

Jack Teeling recalls: ‘While we were still at Cooley, we heard about people making whisky again in London – and we said: “Why the hell isn’t someone doing it in Dublin?” It just didn’t make sense.’

Following the sale of Cooley, Teeling Whiskey was established in 2012. After some difficulties – ‘Dublin City Council was scared of whisky; they thought it was a chemical plant that might blow up’ – the Teeling distillery on Haymarket started production in 2015.

Others have followed – Pearse Lyons in the old St James’ Church and, earlier this year, the new Dublin Liberties distillery. In an echo of precursor DCL’s ill-fated Phoenix Park venture, Diageo is set to open a new George Roe distillery in an old power station on its vast Guinness site in the city later this year.

More than 130 years after Alfred Barnard’s visit, the ghosts of whiskey greatness still linger – the stump of the old windmill that powered the original George Roe distillery, rechristened St Patrick’s Tower and now Dublin’s digital hub; the defunct John Power stills at what is now the National College of Art and Design – but the scent of renewal in the Dublin air is unmistakable.

‘For me, Dublin is still the cradle of distilling in Ireland,’ says Jack Teeling. ‘It wouldn’t be a true revival of Irish whiskey if Dublin whiskey and Dublin distilleries weren’t part of that.’

‘It’s just brilliant,’ adds Quinn. ‘It’s just brilliant to walk around Dublin now and think: “Which distillery shall I visit today?”’