Famed for his explosive outbursts and accident-prone nature, Captain Archibald Haddock is Tintin’s loyal companion for many of the young reporter’s greatest adventures. He is also more than fond of a drop of whisky, as Richard Woodard discovers.

Almost exactly 90 years ago, an idealistic boy reporter with a distinctive quiff made his comic strip debut in Le Petit Vingtième, the children’s supplement of a Belgian daily newspaper. Tintin, accompanied by his faithful dog Snowy, was the creation of Georges Remi, who took his initials, reversed them and fashioned a pen-name based on their Francophone pronunciation: Hergé.

In the decades since then, the Tintin books have sold well over 100 million copies worldwide, and have been translated into more than 50 languages, including Esperanto and Latin. Among Hergé’s cast of unforgettable characters, perhaps the most memorable and popular is Captain Archibald Haddock, Tintin’s faithful, accident-prone and emotionally volatile companion – and whisky plays a vital role in his back-story.

Why the name Haddock? There are several theories, and there was more than one seafaring Haddock in real life, including Herbert James Haddock, who skippered the Titanic during technical trials, and was then captain of its sister ship, Olympic.

Perhaps the most attractive explanation, however, stems from an evening when Hergé is said to have asked his first wife, Germaine, what was for dinner. ‘Haddock,’ she replied, before adding a description of it as ‘a sad English fish’.

We meet Captain Haddock for the first time in Tintin’s ninth adventure, The Crab with the Golden Claws, and it’s a less than promising beginning. Although nominally the captain of his vessel, Karaboudjan, Haddock is in fact in thrall to his first mate, Allan Thompson, who keeps him topped up with whisky while plying his nefarious trade of smuggling opium in crab meat tins.

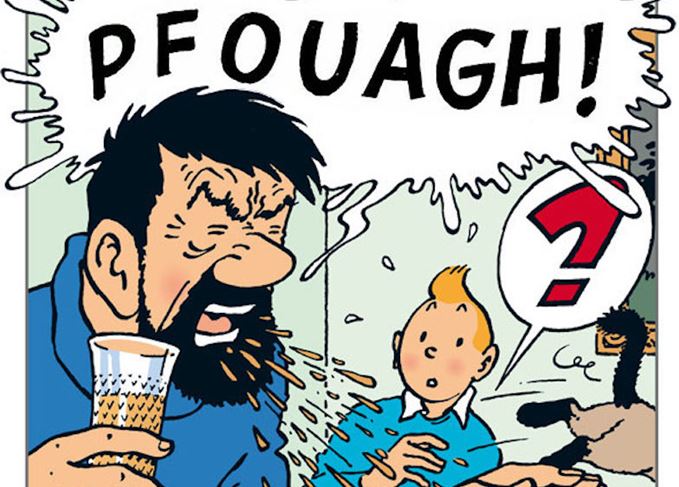

In the first reference to Haddock, Allan Thompson exclaims: ‘The Captain?... What does he want, the old drunkard?’ – and, sure enough, when Tintin is catapulted into his cabin shortly afterwards, Haddock has glass in hand. In the rest of the adventure, Haddock’s drinking is an ever-present danger, whether setting fire to the oars of a lifeboat, or visualising Tintin as a bottle of Champagne when addled by the desert sun.

Ripping yarns: Haddock is central to two of the most famous Tintin adventures

But, by the end of the book, Tintin has saved the day, and saved the Captain in the process, earning in return a lifelong friend and a wholly loyal, if still colourful, companion. Indeed, in The Secret of the Unicorn and Red Rackham’s Treasure, Haddock and his family history are central to the plot. Hergé ranked the former among his best work; the latter remains the best-selling Tintin adventure.

In the broader literary sense, Haddock also saves Tintin. The boy reporter’s relative blankness – quiff and minimally drawn facial features, quiet determination – requires some surrounding colour, which Haddock amply provides. In Tintin: The Complete Companion, Michael Farr writes:

‘Haddock was the very opposite of Tintin. While the reporter was sober and sensible, Haddock was more often than not drunk and impulsive.’

Tintin’s visage is typically implacable, Haddock’s ‘contorted with emotion’; Tintin’s thoughts and speech reasoned, Haddock’s punctuated by creative bouts of pseudo-swearing. Prevented from using real expletives thanks to his young readership, Hergé instead creates for the Captain a lingua franca of unlikely outbursts.

This finds its finest expression in The Crab… when, his whisky bottle smashed by a Berber marksman, Haddock launches into a raging tirade, of which this is only a brief excerpt:

‘Rats!... Ectoplasms!... Freshwater swabs!... Bashi-bazouks!... Cannibals!... Caterpillars!... Cowards!... Baboons!... Parasites!... Pockmarks!...’

His stock phrases – ‘Billions of blue blistering barnacles!’, sometimes abbreviated to ‘Blistering barnacles!’, and ‘Thundering typhoons!’ are regular features in the series.

Throughout the other books, Haddock’s relationship with alcohol remains enthusiastic, but sometimes troubled. In the next adventure, The Shooting Star, his rehabilitation is such that he has become President of the SSS (Society of Sober Sailors) – but he is undone when we see crates of John Haig whisky being carried aboard his ship, Aurora.

Meanwhile, during the two-part Destination Moon and Explorers on the Moon, Haddock’s apparently innocent copy of Guide to Astronomy is revealed to have been hollowed out to accommodate two bottles of whisky.

An episode of weightlessness while aboard a space rocket sees Haddock’s whisky escape its glass in an elusive liquid ball, frustrating his increasingly desperate attempts to recapture it; as gravity returns, the hapless Captain collapses to the floor – before the whisky splashes down onto his face.

Space oddity: Weightlessness causes Haddock’s whisky to have a life of its own

Shortly afterwards, a drunken space walk has almost fatal consequences, leading to a stream of self-pity from the repentant Haddock:

‘I… I’m a miserable wretch… I had a drink… It’s unpardonable… I’m terribly sorry.’

In The Red Sea Sharks, the villainly Allan Thompson returns, prompting an episode that recalls The Crab with the Golden Claws: waking in his cabin, Haddock sees a (painstakingly accurate) bottle of Haig’s Gold Label whisky sitting on the table, a glass already poured to tempt him.

These struggles aside, and despite a propensity for warning people not to fall over hidden obstacles, only to do so himself, Haddock proves himself time and again a faithful companion to Tintin, most notably when offering to lay down his life for his friend, high in the Himalayas, in Tintin in Tibet – a book described by Hergé as ‘a song dedicated to friendship’.

There is also the question of what Haddock drinks. While fond of rum – he is a seafarer, after all – whisky is his first love; specifically – and despite the references to Haig – Loch Lomond whisky, which crops up throughout the books.

In fact, whisky in Tintin predates Haddock’s first appearance. During The Black Island, in which Tintin and Snowy travel to Scotland, a rail tanker of whisky is featured, emblazoned with the words ‘Johnnie Walker Whisky’.

However, in a later edition of 1966, when Hergé’s English publisher Methuen requested a number of changes to modernise the story, the name on the tanker has been changed to ‘Loch Lomond Whisky’. A pub sign for ‘John Haig Whisky’ is similarly altered, while an ashtray brimming with cigarette butts in the villains’ lair also bears the apparently fictitious ‘Loch Lomond’ brand name.

Ironically, the new edition of the book was published in the same year – 1966 – that the modern Loch Lomond distillery became operational in Alexandria, West Dunbartonshire. As far as Hergé was concerned, however, ‘Loch Lomond’ remained wholly made-up.

Guilty secret: Haddock’s presidency of the Society of Sober Sailors is placed in doubt

By the time of the last complete Tintin adventure, Tintin and the Picaros, Loch Lomond – and, indeed, whisky itself – has taken on a more sinister role. As well as sponsoring the local carnival, the brand helps the San Theodoran dictator, General Tapioca, to parachute in copious amounts of whisky to disarm the Picaro rebels, as well as the native Arumbayas.

Even Haddock has had his fill of whisky by this point. Struck on the back of the head by a bottle of Loch Lomond, he suffers temporary memory loss (during which we discover that his first name is Archibald), and even says: ‘No! Enough is enough! Don’t let me hear any more about whisky!’ His love of whisky, like Tintin’s love of adventure, has clearly waned by this point.

There’s something of the slapstick about Captain Haddock, a constant feeling of imminent descent into pathos, or bathos; he provides a colourful and comic counterpoint to the altogether more even-tempered – some would say downright dull – Tintin.

In Tintin and the Secret of Literature, Tom McCarthy writes:

‘It is into irony’s orbit that the Captain is dragged throughout Hergé’s work, and with him is dragged the rest of the world of the Tintin books. He longs for redemption, but finds that every door that purports to offer him this merely leads – if it is a real door at all – into a wider world that is itself a testament to his inauthenticity.’

Authentic or not, Haddock certainly offers humanity as a character, one whose vulnerability is accentuated by his love for whisky, but not defined by it. As Farr says:

‘It is not Haddock’s fondness for the bottle or his human fallibility which makes him the most endearing of characters in the Tintin adventures, it is his irascibility and his unlimited and wonderfully irrelevant repertoire of expletives.’

Put simply, Haddock is fun. Larger-than-life, a comic tool, but one that never forfeits our sympathy or warmth. If McCarthy is right in saying that Hergé’s ‘stupendously rich’ characters ‘…rival any dreamt up by Dickens or Flaubert for sheer strength and depth of personality’ – then Captain Archibald Haddock is the finest achievement of the Belgian author’s art.