Some of the most famous and prized Scotch whisky distilleries fell silent many years ago, mothballed, shut down or demolished – but why? Could they – should they – have survived to enjoy a different fate? Dave Broom reports.

It’s an observed fact that, when some malt lovers are gantry-gazing, one will shake their head and ask: ‘Should Port Ellen have been closed?’ (I’m using Port Ellen as an example; it could be any of the cult distilleries which ceased to exist in the 1980s).

I’d prefer to think of it another way – could Port Ellen have stayed open? The first contains an inference that it was a malicious act, that fault or blame could be apportioned. The second might give an idea of the situation surrounding the decision.

Distillery closures are not unusual. There was a mass cull between the 1830s and 1850s, and a further rationalisation at the start of the 20th century, while 40 closed permanently in the 1920s alone.

In 1933, there were only two malt distilleries in operation and, though the rest of the decade saw a rise in fortunes, the fate of Campbeltown and some Islay distilleries was sealed as blenders followed the public’s changing palate and moved away from the heftier malts which had dominated blends in Victorian and Edwardian times. New malt distilleries – Tormore, Glen Keith, Glenallachie etc – didn’t start being built until the late 1950s and early 1960s.

All of this points to the cyclical nature of the market. Viewed from this wider perspective, it shows Scotch seemingly lurching from boom to bust and back again. The closures of the 1980s weren’t an aberration; they were part of a natural cycle.

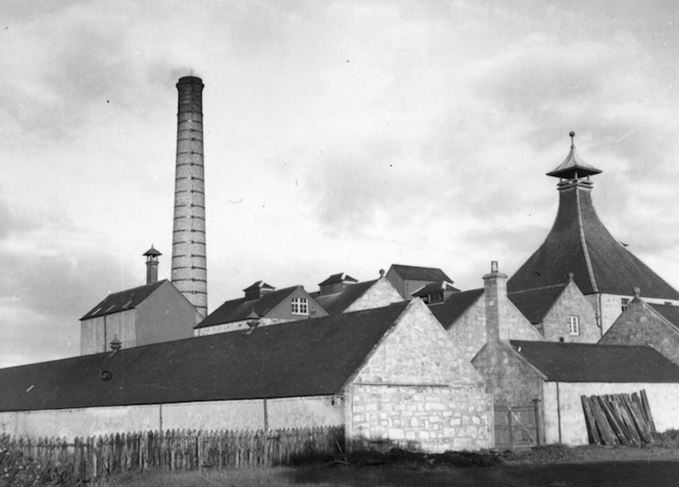

A closed distillery is a sad – even chastening – sight. When it falls silent, a wintry numbness descends and, while it might be too strong to say we grieve for its passing, there is a definite sense of loss – though these days it is often one which is quickly usurped by the realisation that all of those old bottlings might now be worth a lot of money.

Today, it would seem, distilleries are like artists – only reaching fame after their passing. The sense of loss is also more acute because we now have a single malt market. The closing of Port Ellen was little commented on in the blend-centric 1980s.

Why, though, do they close? In simple terms, supply and demand. The whisky industry is always playing a complex guessing game – how much to lay down for potential demand three, 13, or 30 years in the future. Which market will rise, which will stabilise, which will fall?

The forecasters are better now than they were in the late 1970s when the rise in the price of oil, a global economic downturn and a generation turning away from the spirits of the previous two generations impacted sales of Scotch. The industry reacted too slowly, and production continued apace while sales fell precipitously. By the 1980s, the industry was swimming in a whisky loch.

The only upside of this was that there was now plenty of malt whisky to sell – the start of the category as we now know it. The downside was the closure of distilleries.

New era: It wasn’t until the late ’50s that new malt distilleries like Tormore started being built

How were the ones for the firing squad picked? Size was one consideration. If you have one large distillery and one small one, it makes more sense to keep the former open as it has greater flexibility.

Duplication of make was another factor. Remember malt distilleries are there primarily for blending. ‘It has to be said,’ one blender told me once, ‘that the ones which closed were often the ones we considered to make less characterful whisky.’ Not bad whisky, just a make that, when it came to the hard decision, didn’t make the mark.

This then comes particularly into focus with Islay’s distilleries. You don’t need a lot of peat to make a blend smoky, and by the ’80s there was also a trend away from smokiness. If, like Allied, you had Laphroaig and Ardbeg, which one do you choose to remain open? The larger one, the one more important to the blends.

If you had Lagavulin, Caol Ila and Port Ellen, which one has to bite the bullet? The last one, as it’s the smallest; Caol Ila can make peated and unpeated, and Lagavulin is ring-fenced for specific blends. Now apply the same model to the Highlands, or to Speyside.

It seems brutal, but the decisions were not taken by hard-hearted men. While we mourn the ones which closed, we forget how firms kept many more open when it would have made economic sense to close them down. There might have been more painting than distilling taking place in the worst of times, but by fighting against the pressures being applied by accountants, production directors – like the late Turnbull Hutton – kept people in their jobs.

Could it happen again? Of course it could. The industry will hit another cycle, but the number of export markets is now greater than it was, allowing the risk to be spread more widely – especially now the market consists of malts as well as blends. Then again, who can tell with any accuracy what the world will want to drink in a decade’s time?