It was a battle for whisky’s very soul, with pot still purists ranged on one side and lovers of the ‘patent still’ on the other. More than a century after the ‘What is whisky?’ legal wrangle, Gavin D Smith looks back on an episode that shaped the whisky industry as we know it today.

With a number of recently-established Scottish distilleries likely to strain against the bonds of the existing legal definitions of Scotch whisky, it seems an appropriate time to look back at a momentous but often overlooked episode in the history of the spirit, when the distilling industry in Scotland and Ireland took part in the debate about ‘What is whisky?’.

The episode in question took place during the first decade of the 20th century, but it had its origins in a highly publicised campaign by Irish pot distillers, which culminated in the publication of Truths about Whisky in 1878.

The book, essentially a diatribe against the ‘evils’ of column or continuous distillation, was commissioned by the four most influential Irish distilling houses: Messrs John Jameson & Sons, William Jameson & Co, John Power & Son, and George Roe & Co, all based in Dublin.

Until blended Scotch whisky took the world by storm in the later years of the 19th century, Irish whiskey was a far more popular drink than single malt Scotch, both at home and abroad.

It was perceived as being smoother and more consistent than its Scottish counterpart, partly due to the large size of Irish pot stills compared to those used in Scotland.

The most productive of the Irish distilleries in the 1870s was that of George Roe, which had the capacity to make around 9m litres per annum. Even today, that would place it among the largest of Scotland’s malt distilleries.

Joint endeavour: Four Irish distilling houses combined to publish Truths about Whisky

Not surprisingly, in the face of stiff competition from blended Scotch, the Dublin pot still distillers were determined to try to ensure that only their product could be claimed as true ‘whisky’ – the spelling (without an ‘e’) they themselves used.

Their essential definition of whisky was ‘…a spirit which is distilled either from malt, or a mixture of malt or unmalted corn, from barley or oats, or malt, or from a mixture of them, in a so-called pot-still, which brings over, together with the spirit, a variety of flavouring and other ingredients from the grain’.

In refusing to acknowledge the validity of blending pot still and patent spirit and calling it whisky, they sowed the ultimate seeds of their own downfall, though the disastrous decline in Irish whiskey was also aided by the loss of British and Empire markets during the Irish War of Independence (1919-21) and the subsequent creation of the Irish Free State. Only in the 21st century are we seeing a real renaissance in the Irish whiskey industry.

But they weren’t alone. The early 1900s saw Scottish malt distillers taking a similarly defensive position to their Irish counterparts, as spirit supply greatly exceeded demand, and the entire Scotch whisky industry faced difficult times.

The highly influential Distillers Company Limited (DCL) was a blending-led operation which set out to buy up and either close or reduce production at a notable number of patent still Lowland distilleries, enhancing its already powerful position in controlling grain whisky supply in the process.

A number of leading Highland pot still producers effectively took a stand against DCL, despite the fact that they were now significantly dependent on blenders to buy their ‘make’.

Heartfelt plea: Dalmore owner Andrew Mackenzie praised single malt to customers

They declared that only the product of pot stills should be legally termed whisky, drawing on evidence that had come to light during investigations into the Pattison Crash, to the effect that some Pattison blends contained only very small amounts of malt, and not far short of 100% grain spirit.

In 1903, Andrew Mackenzie, owner of Dalmore distillery, wrote to customers declaring that:

‘Once one gets initiated to a “pure Highland Malt” or “Self” whisky that is the product of one Distillery it is invariably preferred to the best of Blends, but it requires a little education at first with people who have never taken it before.’

The pot still distillers’ lobbying culminated in a prosecution in the unlikely setting of the London Borough of Islington during 1903, which was ultimately to provide the essential definition of Scotch whisky which still pertains today, and allow the establishment of the blending business as pre-eminent.

In their own way, this prosecution and its consequences were as vital in shaping the modern Scotch whisky industry as the invention of the patent still almost a century previously.

Islington Borough Council prosecuted two merchants under the provisions of the Sale of Food & Drugs Act 1875 for selling whisky ‘...not of the nature, substance and quality demanded’.

The Distillers Company paid the defence expenses, so important was this test case, but the verdict went against the merchants, with the magistrate who heard the case declaring: ‘I must hold that by Irish or Scotch whisky is now meant a spirit obtained in the same methods by the aid of the form of still known as the pot still.’

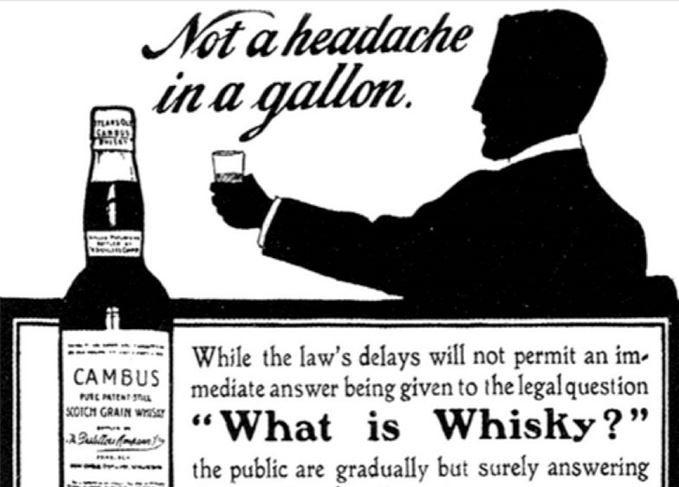

Click to expand: DCL’s Cambus advert alluded provocatively to the ‘What is whisky’ case

An appeal was immediately launched, but it proved inconclusive, with arguments between the malt distillers and the grain distillers and blenders continuing.

DCL managing director William Ross took to promoting seven-year-old Cambus Patent Still Scotch Grain Whisky in a national press campaign during 1906. Provocatively, the advert took pains to point out that Cambus was ‘…not a Pot Still Whisky’, using the slogan: Not a headache in a gallon.

In February 1908 the government announced that a Royal Commission on Whiskey and Other Potable Spirits was to be established to examine the issue.

The proportions of malt and grain whisky that might be included in blends was debated, with the pot still interest conceding that a 50/50 mixture would be acceptable to them. Minimum maturation periods were also put under the microscope.

Ultimately, after no fewer than 37 sittings, the Commission concluded in its report of July 1909:

‘...that “Whiskey” is a spirit obtained by distillation from a wash saccharified by the diastase of malt, that “Scotch Whiskey” is whiskey, as above defined distilled in Scotland.’

No compulsory maturation period was stipulated, and no minimum percentage of malt required in a blend was specified. It was a complete victory for the blenders and patent still distillers. Cambus Patent Still Scotch Grain Whisky once again quietly resumed its place in the blending vats of the Scotch whisky industry.

Bitterly resentful: Sir Robert Bruce Lockhart decried the decision of the Royal Commission

Nonetheless, the perception that only malt whisky was ‘true’ whisky persisted in some influential quarters.

Writing in his 1930 volume Whisky, Aeneas MacDonald declared of the ‘What is Whisky?’ ruling that:

‘It is difficult not to regret that the battle went on that occasion to the strong in numbers and wealth, and that the final decision was in the hands of those who were ignorant of what whisky really is.’

Twenty-one years later, Sir Robert Bruce Lockhart echoed MacDonald’s lament in his book Scotch, writing that:

‘The decision, made by a Commission… composed mainly of Sassenachs who knew little or nothing about the special merits of whisky, was a serious blow for the malt distillers who were bitterly resentful.’

He adds:

‘Expression was given to their indignation by the Duke of Richmond and Gordon… Speaking at Glenlivet soon after the Royal Commission’s decision, the Duke declared amid loud applause: “Quite recently a public enquiry has taken it upon itself to decide what is whisky. And I regret to say that anything that is made in Scotland, whatever its combination, is to be called Scotch whisky.

‘“For my part, I prefer, and I think that most of those who I am addressing now would prefer to trust to their own palates, than to the dogma of chemists…”’

Blended Scotch has, of course, continued to be a formidable global force, but advocates of ‘pure pot still’ have much for which to be thankful. The variety and international availability of Scotch single malts has never been greater, and the share of revenue earned by malts as a total of Scotch whisky exports has grown to 26%, hitting the £1bn mark for the first time in 2016.

Additionally, with so many newcomers to the Scotch whisky sector, the future for single malt looks extremely positive, even though some of those newcomers are likely to push the boundaries of existing legislation, and new battles about ‘what is whisky’ may once again be on the horizon.