Scotland has long been considered the birthplace of single malt whisky, but with countries across the world producing their own – well received – versions, is single malt still considered inherently Scottish? Tom Bruce-Gardyne chairs the debate.

It is no wonder that whisky makers the world over have woken up to single malts. Within Scotch whisky it is clearly the most buoyant category right now, certainly in the big mature markets likes America. Fifteen years ago, of all the Scotch sold in the States only one bottle in 12 would have been a single malt, whereas today it would be close on three bottles. And we’re just talking volume. In terms of value, Scotch single malts may soon overtake blends in the US.

So, of course American distillers want a piece of that, as they do in Taiwan, Tasmania or just about anywhere producing whisky with the exception of Ireland and its pot still Irish whiskey. But tot up the entire production of global single malt and you would still have barely a drop compared to what flows out of Scotland.

Inevitably that drop will expand over time, and there will be a growing number of blind tastings of single malts which the Scots won’t necessarily win. No doubt in a future edition of his Whisky Bible, some Patagonian Port pipe malt is destined to scoop Jim Murray’s ‘World Whisky of the Year’ award. It will make headlines in Patagonia, but perhaps nowhere else. Back in the real world, let’s just ask… is single malt still synonymous with Scotch?

YES: IAIN MCALISTER, MASTER DISTILLER AND DISTILLERY MANAGER, GLEN SCOTIA

As someone who produces single malt Scotch whisky in the smallest recognised whisky region in Scotland, I would have to say that yes, absolutely, the two are synonymous. Single malt whisky produced from only water and malted barley at a single distillery by batch distillation in pot stills, undoubtedly represents the apex of Scotch.

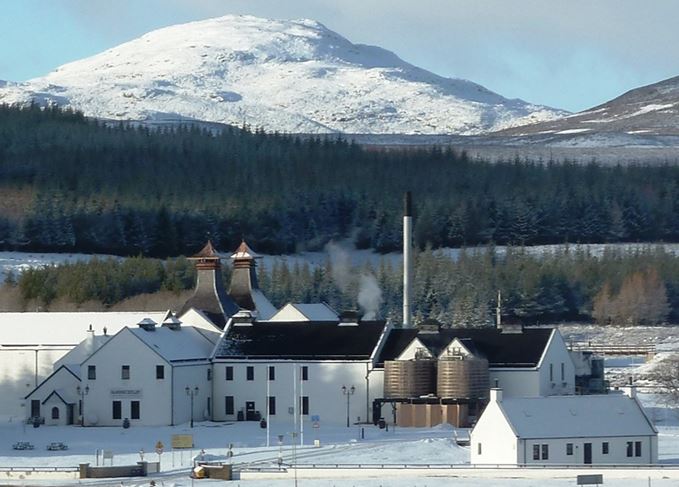

The secret is in the name… Scotch. This is perceived as being the benchmark and ultimate quality grade to aspire to, because single malts produced in Scotland are the pinnacle of the whisky industry. I acknowledge that you can find great whiskies around the world and there are some fantastic distillers who are closing the gap with Scotland in terms of quality, but Scotch single malts are what many continually try to match, both in quality and in trying to capture some of the romanticism, provenance and sense of history. That will always be a difficult exercise, however, because while you can improve product quality you can never bottle that same provenance. Our water, geology and local climatic conditions are always going to be unique to this part of the world.

If we consider the unprecedented rise in the global market for single malt Scotch whisky in recent years, then it has to be a direct consequence of the worldwide desire to taste and experience a product that is crafted in Scotland. Looking at this symbolism in the global concept, there is a natural aspiration among others to develop a product and call it a ‘single malt’ despite, or perhaps because, the name is so closely associated with Scotch.

I was lucky enough to be born and bred in Campbeltown, a truly wonderful corner of the world. From my earliest days, I was told the story of Campbeltown whisky and how it was unique, and could never be replicated. Part of my job as distillery manager is to meet the enthusiastic visitors who make the pilgrimage to Campbeltown and Scotland in general. Of course the reason they come here is because this is nirvana – the ancestral home of whisky, and for me, it confirms the world’s love affair with those four simple words: Scotch single malt whisky.

NO: CLAY RISEN, AUTHOR, EDITOR AND WHISKY WRITER

I understand why some people in Britain worry about the rise of global single malts which are suddenly being made in Sweden, France, India, Taiwan, the United States… you name it. But there’s nothing inherently Scottish about single malts – nor should there be. The Scotch Whisky Association (SWA) left the door open, after all. ‘Single malt,’ as it defines the category, is made at a single distillery, in a pot still, using only malted barley. As long as it’s not called ‘Scotch,’ it can be made anywhere. So thank you, SWA.

Of course, definitions are one thing, tradition another. But let’s consider the history. As much as the Scottish would like to claim single malts as an ancient heritage, it is a recent development. Of course Highlanders were making their own distillates for centuries (though almost always unaged), and ‘pure malts’ had a strong following in the late 19th century, but as a commercial category, it didn’t really gain traction until well after World War II. That means the Scottish single malt, as a mainstream category, is only a few decades older than the first wave of American single malts in the 1980s.

But even if Scotland did have a long-held grip on the category, it goes against Britain’s cultural DNA to keep it to itself. In the same way that a mongrel language evolved on a medium-sized island on the edge of Europe to become the global lingua franca, a distilled spirit that immigrated to the Scottish Highlands from Ireland is now the world’s most popular liquor. And if the English spoken in North America, India and Australia is different from the mother accent and dialect, is it any surprise that those same countries would develop their own iterations of the mother spirit?

Scotch whisky could use a shot of extra-territorial competition. Scotland has arguably never seen better distilling teams working with better equipment to supply better-informed single malt consumers. What’s lacking is innovation – thanks to the strictures imposed by the SWA who regularly say ‘no’ to requests like Diageo’s to age whisky in ex-Tequila barrels. Contrast that with the United States, where distilleries are going wild with innovation, making single malt from commercially ready beer and ageing their whisky in all manner of barrels.

Many of these innovations will fail – honestly, would you drink Tequila barrel-aged whisky? But some will succeed, and a much smaller number of those will change the whisky market in ways we can’t predict. The global spread of single malt creates an opportunity for Scotch to learn by example. Consider global single malts as a test lab, where wild innovation can percolate before being adopted back home. It may not feel like the traditional thing to do – but then what is tradition, if not a delaying tactic before accepting inevitable change?

IN CONCLUSION...

Risen is a fan of single malt Scotch whisky – the subject of his latest book (see: www.clayrisen.com), but he makes a good point about tradition, and the need to embrace innovation. However, when it comes to history he may be on more shaky ground given that single malt whisky is what Scotland has produced since at least the late 15th century, whether it was aged or not, while blended Scotch is a largely Victorian creation.

Meanwhile, Iain McAlister is right to stress the importance of provenance over process. When whisky drinkers buy a bottle of his single malt they are buying a little piece of Campbeltown as much as the liquid inside, and that’s something no-one from elsewhere can replicate. Glen Scotia has been distilling on and off since 1832, which gives the brand a depth of history that distillers on the other side of the world can only dream of.

But clearly they have their own provenance to talk up, and far fewer rules to fence them in. They can be more experimental than Scottish distillers and maybe some of their ideas will percolate back to Scotland eventually as Risen suggests. For now, if only in terms of scale, Scotch and single malts would seem to be pretty synonymous in the minds of most whisky drinkers. One can only hope the Scots ignore that comforting thought, and keep striving to make the best whisky they can.