Novelist Neil M Gunn was one of the leading figures of the Scottish renaissance of the early 20th century. But long before he established himself as a writer, he was an exciseman whose work took him frequently to Scotch whisky distilleries. Gavin D Smith tells his story.

Neil Miller Gunn was born at Dunbeath on the Caithness coast in 1891. At that time, herring fishing was a booming industry, providing a living for many folk in the Highlands and Islands, and Gunn’s father was skipper of a successful fishing boat.

In 1911, Gunn entered the Civil Service, and was posted to London and Edinburgh before returning to the north of Scotland as a Customs & Excise official.

Based in Inverness, he worked as an ‘unattached officer’, covering for periods of holiday or illness all over the Highlands and Islands and dealing with all matters that concerned Customs & Excise – though it seems that he particularly enjoyed his visits to distilleries.

Through the excise service, he made friends with another officer who would also go on to be a successful novelist, the Kerry-born Maurice Walsh. Gunn described to his co-biographer Francis Hart how, while Walsh was stationed at Benromach distillery in Forres: ‘I’d write ahead and say: “Look here! I’m coming to replace you. Kindly see that the books are all in perfect order and that there is absolutely no work to be done.”’

The pair would fish and shoot all over the Highlands, and Gunn features in Walsh’s best-known novel The Key Above The Door, published in 1926. He is fictionalised as Neil Quinn, who invites the narrator to stay with him near Talisker distillery on Skye, where he is covering for the resident officer’s period of leave.

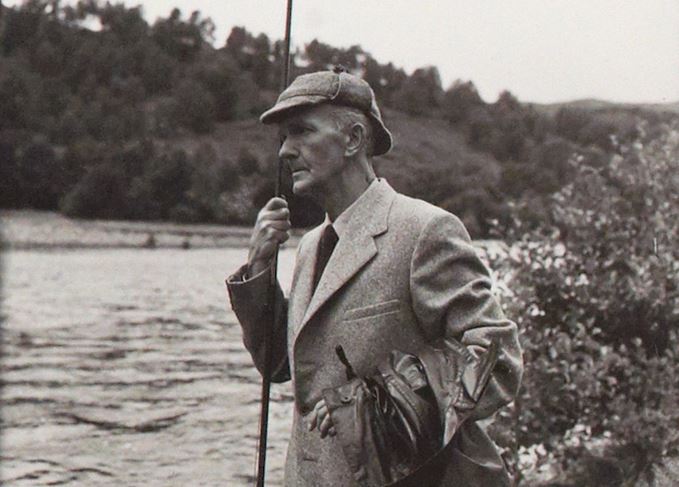

On the road: Gunn spent his early career as a travelling excise officer in the Highlands

The visit was real enough, and Gunn later recalled that the pair stopped off at an inn on their way home from a day’s fishing for ‘two drams of Talisker whisky, 12 years old, out of a Sherry hogshead’.

In 1921, Neil Gunn became eligible for his first fixed assignment, and one of his fellow officers joked that he would probably be sent to Wigan. And sure enough, when the orders came through, Wigan it was!

While there, he married his fiancée Daisy, and after a year the couple returned to the Highlands, with Gunn appointed as resident officer at Glen Mhor distillery in Inverness in 1923. Glen Mhor and its neighbour Glen Albyn were then owned by John Birnie, who became a friend and mentor to the new officer.

The ‘exciseman’ was unquestionably the most powerful figure in any distillery, as he was the representative of HM Government with the authority to stop whisky-making if he was not satisfied that all proper practices were being observed to ensure that the government received its full duty payment.

As Gunn himself wrote, however:

‘Long experience has created an almost perfect system of supervision, interfering so little with practical operations and supplying such figures of liability or accountancy as distillers unhesitatingly accepted, that normally the relations between the Excise official are pleasant and charged with mutual respect.’

Certainly, Gunn found time to spend most afternoons at home writing, while the business of distillation carried on. His literary career blossomed, and in 1937 he felt sufficiently confident in making a living from it that he resigned from the Excise service and took to writing full-time.

On the beach: Gunn didn’t let his job as exciseman interrupt his writing endeavours

Of the 27 books he published, the best known is undoubtedly the 1941 epic novel about the fishing boom of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, The Silver Darlings. A website devoted to the author declares it to be ‘widely acclaimed as a modern classic and considered the finest balance between concrete action and metaphysical speculation achieved by any British writer in the 20th century’.

Two years before leaving Glen Mhor, Gunn penned Whisky and Scotland, subtitled A Practical and Spiritual Survey and described by publisher George Routledge & Sons as ‘this witty, indignant little book’.

As a writer about whisky, Gunn is the antithesis of the Victorian ‘distillery-bagger' Alfred Barnard. Whereas Barnard took delight in chronicling the dimensions of everything he saw in each distillery he visited, Gunn was much more of a broad-brush man.

For him the mystique of whisky-making and its role in Scottish history, legend and everyday life was what made it worth writing about, though he also demonstrates the ability to describe traditional whisky-making practices in clear and engaging terms.

Faced with a washback, Barnard would have asked its capacity, whereas Gunn wrote: ‘I have heard one of those backs rock and roar in a perfect reproduction of a really dirty night at sea.’

Whisky writer: Gunn was interested in the broader cultural context of Scotch

This is a whisky book written by a writer, rather than a book written by a whisky writer. Just consider the lines: ‘To listen to the silence of 5,000 casks of whisky in the twilight of a warehouse while the barley seed is being scattered on surrounding fields, might make even a Poet Laureate dumb.’

Gunn’s is also a book about much more than whisky, with the subject only really receiving dedicated coverage from page 125 onwards out a total of 198. For Gunn, Scotland’s whisky and its heritage are inextricably interwoven with its nationhood, and the ardent Scottish nationalist – and ally of poet and essayist Hugh MacDiarmid – has much to say on the subject.

He also has much to say about the prevailing fashion for light-bodied, easy-drinking blends, declaring that ‘…the blender has become the dictator of the pot still, whose product he uses. To survive, the pot still must sell as cheaply to him as possible and must therefore contrive to get the maximum amount of spirit out of the minimum amount of barley’.

He further writes:

‘A fine pot-still whisky is as noble a product of Scotland as any Burgundy or Champagne is of France. Patent-still spirit is no more a true whisky than, at the opposite extreme, is any of those cheap juices of the grape heavily fortified by raw spirit which we import from the ends of the earth a true wine.’

Gunn was, of course, writing at a time of global economic depression, to which the Scotch whisky industry was far from immune. He notes:

‘In 1921 there were 134 distilleries at work in Scotland. In 1933 there were 15 (including six patent stills). Last year, the number of pot stills at work had increased again. But the future of Highland malt whisky, other than as a flavouring ingredient of patent spirit, is very obscure.’

Neil Gunn died in 1973 but, were he alive today, he would surely take great pleasure in the renaissance which single malts have undergone during the past few decades.

He would also have delighted in the number of independent distilleries that are springing up all over Scotland. He would, however, have been rather less thrilled about the result of the 2014 referendum on Scottish independence…