Six years, six Dramborees… and then no more. From Aberfeldy to Loch Lomond, this was a whisky festival ‘forged by a raggle-taggle community’, but 2018 was the year that Dramboree took its final bow. Angus MacRaild reports.

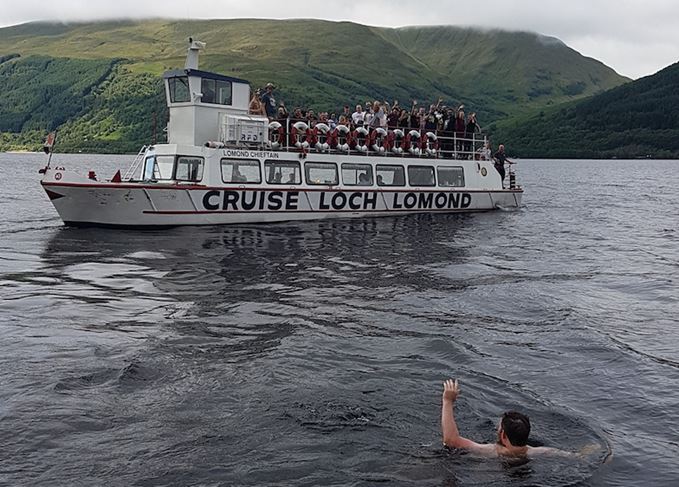

It started as a nocturnal, Maltstock-inspired, dram-fuelled bout of imagination between two friends and ended with a bout of tidying up and some final Loch Lomond plunges outside Rowardennan Youth Hostel.

The first instance was the notion that ‘this sort of thing should (could?) happen in Scotland’. Six years later saw the conclusion of the sixth and final edition of the event that was to become known as ‘Dramboree’. In between? Rather a lot of ‘stuff’ happened.

Ask some of the various attendees over the years what Dramboree means to them and invariably you’ll hear such declarations as ‘loony dook’ or ‘those surprisingly loud horns’.

Also swimming, the dram table, that day with Stephen Marshall, 19th-century beers, midgies, ‘Herwynne’, Lord and Lady Springburn, techno, that time Blair Bowman cradled a Henry Hoover, ‘the salmon cannon’, Ben’s barbecue, Webb’s awful whiskies, ‘who is this Jon Beach guy anyway?’, Forbes and the giant Haig Club and – inevitably – ‘that fish mask’.

If all that sounds a little ‘in-jokey’, that’s probably because Dramboree was limited to 60 places, and many people returned on multiple occasions. It was a festival forged by a raggle-taggle community of characters, tastes, opinions and whiskies; its eccentricities and finer qualities heightened by the limiting realities of organising such an event in Scotland.

First time: Attendees gather for the compulsory group photo at the first Dramboree in 2013

There are very few Scottish venues that you can book for that number of people at a realistic price in summer, and which are proximate to distilleries. So Dramboree was a festival where success rested disproportionately upon the qualities of those who organised and attended it.

The first Dramboree took place in 2013 in Aberfeldy. Only 30 people attended, but it was to set the mould for future events – a communal ‘dram table’ where people laid out the bottles they had brought for sharing, a selection of tastings which included themes from old and rare whiskies to a sneak peak at maturing Daftmills, games, a quiz, communal dinner and breakfast, an in-depth visit to Aberfeldy and – inevitably – a considerable amount of late-night revelry.

The sixth and final Dramboree concluded this just over a week ago. While the core architecture of the festival has remained largely consistent, it has been interesting to note the subtle reflections of the wider, evolving whisky scene over the previous half-decade.

Since 2013, in the UK’s domestic whisky scene, we’ve seen a newer generation of whisky enthusiasm emerging – one which is social media-savvy and increasingly dislocated from the whisky world of the past, both by choice and by the brutal financial realities of buying older bottlings.

Also, while interested in the global whisky scene, this newer generation is often focused on domestic Scottish companies, products and distilleries. There has also been a significant ‘fusing’ of craft beer with whisky enthusiasm, as well as a lateral, burgeoning interest in alternative spirits, chiefly among them gin, but also rum and brandy.

Hung up: Organisers Jonny McMillan and Jason Standing used their horns to capture people’s attention

In Dramboree you could see some of these trends in microcosm, such as the way each year saw an increasing interest in beer, to the extent that we discussed and co-ordinated privately what beers we were bringing to a similar extent as we did our whiskies.

The final two Dramborees saw people bringing advanced home brews, as well as what can only be described as ‘old and rare’ or long-aged beers to open out of enthusiastic – if arguably reckless – fascination.

This year saw a tasting hosted by Billy Abbott and Ivar Wittebrood that paired beers with alternative spirits, which included genevers, a gin and American rye whiskey – an event that would have felt out-of-place at Dramboree only a few years previously.

The composition of the dram table was also a good barometer of wider cultural tastes and trends. The first year saw old and rare whiskies demolished with no-nonsense fervour.

However, in recent years, these sorts of whiskies started to become overlooked in favour of more ‘talked about’ recent releases, such as official single cask bottlings, independent releases which had made a name for themselves, and even world whiskies which had garnered online attention.

What might have been described as ‘obvious’ in previous years has clearly altered in recent times. It has been fascinating to watch something as simple as the Dramboree dram table illustrate a shift in cultural perception about whisky, and in particular, perceptions of quality and desirability surrounding it.

Last time: Attendees at this, the final Dramboree whisky festival

On the flip-side, those who this year tasted an old bottle of Laphroaig 10-year-old bottled in the 1980s were often taken aback at just how distinct it was from their established conceptions about that distillery’s character.

In illustrating how tastes change, a festival such as Dramboree has also worked as a reminder of what is being forgotten about whisky, or what the majority of whisky enthusiasts are being priced out of these days, to the extent that they have little choice but to root their passion in new products and companies.

Speaking on the evolution of Dramboree over the years, co-organiser Jonny McMillan said: ‘Initially, we just wanted to get people away from Twitter tastings and exchanging tiny samples in the post... back to havering with pals into the night – basically, what makes whisky drinking great.

‘That and whisky always tastes better in the Highlands... We’ve been really amazed at how the dynamic has grown and evolved... there was a whole crop of younger whisky drinkers there this year, learning, having fun and making friends... needless to say, for Jason and I, it’s been a pretty touching experience.’

McMillan’s fellow organiser Jason Standing added: ‘It was really quite something to see how the people we approached got excited about being part of Dramboree... I'd never in my wildest dreams imagined I'd see a talk by a research chemist who'd analysed peat levels in the bottle and then used lab equipment to produce a whisky at over 80ppm in bottle!

Lotta bottle: The evolving composition of the dram table has been a bellwether of whisky

‘Looking back, I’m very pleased with what we brought to life for six years – the number of friendships and connections established. I’m definitely going to miss it.’

If nothing else, this final Dramboree served as a reminder that whisky is not reliant on pomp and finery for the realisation of its ultimate potential: to bring people together in a cradle of shared enthusiasm, joy and celebration.

It was an unfussy event; the antithesis of glitz, polish and prestige. Humble in its initial ambitions, it was inclusive, easy-going and put the raw enjoyment of whisky at its core. It’s a shame that so few people, relatively speaking, were able to attend Dramboree over the years. But, then again, its size was integral to its charm.

Dramboree was an island, distant from the doldrums, realities and stresses of real life. We laughed, geeked out, tore the piss out of each other with merciless glee, threw ourselves into the waters of its shores (with swimwear... most of the time) and, most importantly, had a riotous amount of fun.

Friendships were forged, a few romances kindled, the world was put to rights many times over and great memories were created. A whisky festival can do little more.