Once Scotland’s most easterly distillery, Glenugie’s whisky was mostly destined for blends during its lifetime, but has grown in stature since. With the last of Glenugie’s warehouses about to be demolished, Thijs Klaverstijn looks back at the Peterhead plant’s history, focusing in particular on its last 12 months of operation.

The year 1983 is one of the most notorious in whisky history. It was the height of the recession in the industry, when about a dozen malt distilleries were closed. The most famous are Brora and Port Ellen, but many others also fell silent.

One of these was Glenugie, located in Peterhead, a little north of Aberdeen. Scotland’s most easterly whisky distillery, it was owned by Long John International at the time and, according to the Aberdeen Press and Journal, it had the dubious honour of being the first distillery to be shut down on the Scottish mainland during the crisis of the 1980s.

Glenugie was highly regarded throughout its history: in the late 19th century, Excise officers were particularly impressed by its mash and still house, which was very commodious and well-ventilated, making it, in their eyes, one of the best distilleries in the north of Scotland.

Even today, the whisky made at Glenugie is widely admired by whisky enthusiasts. Glenugie collector Bob Hulsebosch describes the spirit as ‘exotically fruity and characterful’, and finds that Glenugie combines the best of old Springbank, Brora, Lochside and Clynelish.

Long-time Long John International employee Sid Watt, now retired and living in Glasgow, is similarly fond of Glenugie, although he stays away from the superlatives. ‘It was regarded as a light-flavoured Highland malt,’ he says. ‘It’s a nice wee drink, if you can get it.’

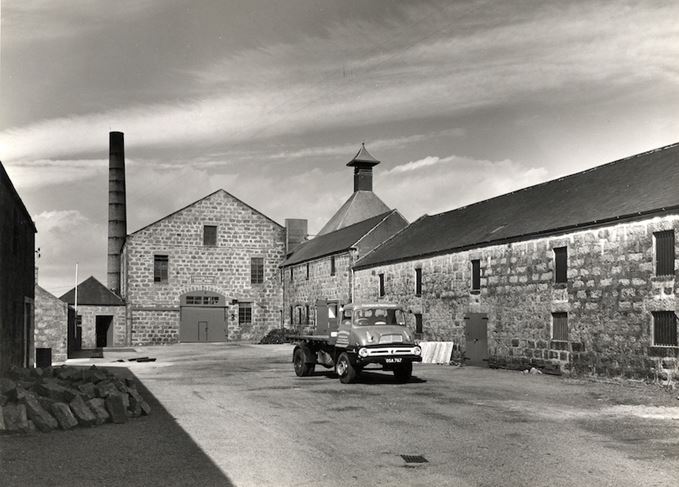

From the air: Glenugie distillery was very highly regarded during the 19th century

Watt was sent up to Glenugie in 1983, to oversee the removal of all the whisky maturing on-site. Together with four men from the warehouse crew, the job was supposed to last six months, but it took them nearly 10 months to clear the place.

Watt started his career in the whisky trade in 1966, working in a spirit store. At Long John he spent time in the sample room, working in the blending hall as well. But the year he was tasked with managing the final stages of Glenugie stayed with him the longest. ‘I was the one that shut the place down,’ he says.

Filling two lorries a day with about 100 casks each, it was a long and laborious job. At the start, only one antiquated stacker was available to the crew. Money was tight, as the whisky industry was haemorrhaging cash, but Long John found the funds to rent a forklift truck. ‘That stacker was slow! If it wasn’t for that forklift, we might’ve still been there,’ Watt says.

It wasn’t until long after its closure that Glenugie made a modest name for itself as a single malt whisky. When the distillery was still in operation, most of the liquid was used in the Long John blend, while only the occasional cask was sold to private individuals.

Big task: Sid Watt and his colleagues were charged with emptying Glenugie’s warehouses

Watt and his crew encountered one such cask when emptying the warehouse. ‘That’s one I’ll never forget. It was maybe 60 years old. We couldn’t find out who the owner was. This person hadn’t paid rent on it for a while too, you know, to store the cask. So the company took it back into their stock.

‘You’d have thought there would’ve been almost nothing left in it because of evaporation, but there was still some in it. That whisky would be very valuable, but I’ve no idea what they did with it. Probably sold it to a broker to cover the rent or something.’

Located close to the coast, Glenugie had some sinister neighbours. The Peterhead Prison opened in 1888 a few hundred yards from the distillery. More than once a prisoner escaped, most notably Johnny Ramensky, also known as Gentleman Johnny. A career criminal, he used his safe-cracking skills as a Commando during the Second World War.

During the third of a total of four escape attempts in 1958, distillery workers from Glenugie spotted Ramensky as he tried to make his way out of Peterhead. Alexander Allan told the Aberdeen Evening Express: ‘A colleague and I ran after him. He hid behind some bushes (…), and, when we came up, he belted along past the warehouse and over the wall.’

Because of occurrences like this, assistant distillery manager William Bain, one of Sid Watt’s best friends, kept a pickaxe handle near his front door. One day in 1983, when Watt came into work, a long line of cars was outside Peterhead Prison. ‘Being very naive, I thought: “Well, maybe this is the day they let out the prisoners that are due to be let out,”’ he recalls.

Hard labour: Sid Watt was very impressed with the attitude of Glenugie’s workers

It turned out that some inmates had escaped onto the roof of the prison. The solution for this problem was found at Glenugie distillery. ‘We had a fire engine with a portable pump,’ says Watt. ‘They used water from our fire dam, which we had for safety purposes.

‘As this was in December, the water was freezing and murky, not something you want to be hosed down from a roof with. But that’s what they did.’

In between the hard work and prison escapes, Watt and his crew had some good times, especially when a Customs and Excise officer asked if he could store a sports car in one of the empty Glenugie warehouses.

‘They confiscated it from someone who hadn’t paid the import tax. I don’t remember the brand, but it was blue. Sometimes we took it out in the yard. It was quite nice to have a wee drive around in this high-powered car.’

When the final day of work came around, it was just like any other day, according to Watt. The lorry came in early and they had the last cask away at about 10am. He praises the men he worked with, who knew they were about to lose their jobs.

‘They had a lovely attitude towards it. They all knew what was going on and were working towards it. It didn’t affect the way they worked – I would love to have worked with them even longer.’

Silent stills: Glenugie was one of the first casualties of the 1980s ‘whisky loch’

With the last casks on their way out of Peterhead, the remaining distillery workers and Watt had a small party. ‘There was quite a lot of stock – bottles of whisky and all that – left in the store room. We handed some out to local pensioners. Three bottles we handed in to the local lifeboat station, so they could raffle them. The men took some home as well.’

After Glenugie closed its doors for the last time, part of the equipment was sold. The spirit safe and the mash tun ended up at Fettercairn, while some of the stainless steel tanks found their way to Ben Nevis.

The distillery buildings have been in use over the years, but due to site redevelopment by current owner Score Group, most of the existing buildings fell into disrepair and were demolished. One set of warehouses remains today, but is scheduled to be knocked down soon, to make room for extra storage.

Watt is sad to hear the news, as he has many fond memories of Glenugie and Peterhead. Over the years he stayed in touch with several of his former colleagues. ‘It was a great atmosphere up there,’ he says. ‘I returned several times, and went up maybe once a year.

‘I always drove past the distillery, and was sad to see the way it went. If I could’ve possibly done it, I would’ve moved there. Had the distillery stayed on, I would’ve applied for a job at Glenugie.’