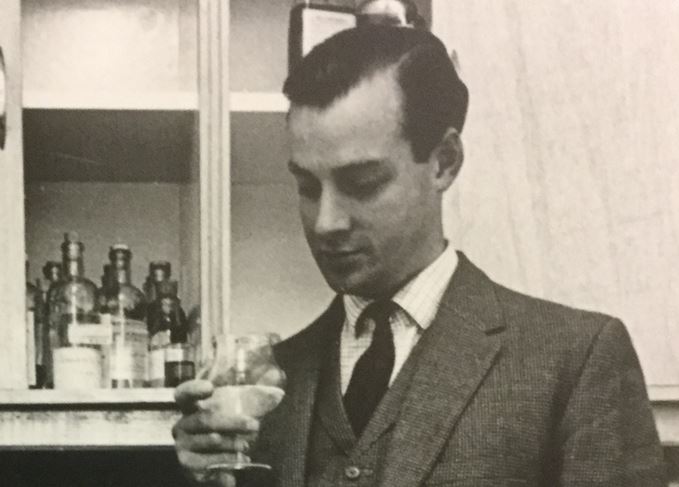

Tributes have been paid to Hugh Mitcalfe, the ‘marketing genius’ behind the rise of single malts Glen Grant and Macallan, who has died at the age of 84.

Mitcalfe, who died ‘peacefully’ on 2 January, spent nearly 20 years at Glen Grant – a time of huge success for the Rothes single malt, especially in Italy – before moving to Macallan and helping to transform it from a little-known Speyside distillery into perhaps the world’s most recognised malt whisky.

‘He left an indelible mark on Glen Grant,’ said Dennis Malcolm OBE, Glen Grant master distiller. ‘Through his endeavours, Glen Grant really made it in Italy… We were selling nearly half a million cases there in the 1970s.’

‘Hugh Mitcalfe was the marketing brain behind The Macallan,’ added Willie Phillips, Macallan MD from 1978 to 1996. ‘I keep saying to people, when they say “you built The Macallan”; no, my team built The Macallan, and Hugh was an important part of that team.’

In the 1980s, Mitcalfe developed Macallan’s ‘Anniversary’ expressions, starting with a 25-year-old, and moving on to a 50-year-old and a 60-year-old, a bottle of which recently sold for more than £1m at auction.

‘Hugh was intimately involved in every stage of The Macallan’s transition from being a top-class malt for the blenders into a powerful brand in its own right, thereby laying the foundations for the global fame to come,’ said David Cox, previously a director of The Macallan Distillers Ltd, now retired.

Whisky writer Charlie MacLean added that Mitcalfe’s contribution to the history of Scotch malt whisky ‘must not be underestimated’ – particularly his work in Italy with Glen Grant, and then with Macallan.

Italian visitors: Mitcalfe (centre left, dark glasses) with Douglas Mackessack (kilt) and representatives of Glen Grant’s Italian importers at Inverness Aerodrome in 1961

HUGH MITCALFE (1934-2019)

Hugh Mitcalfe joined Glen Grant in 1959 as export and marketing director; he was the son-in-law of distillery owner Major Douglas Mackessack, having married his daughter Kirsteen.

‘What I did like about him was that he came as the boss’s son-in-law, but he ended up spending the better part of a year at the plant, learning from the bottom up,’ recalls Malcolm.

‘He came to the maltings at Caperdonich. He came to the cooperage when I was working there, learning how to build a cask. He wanted to know everything.’

Mitcalfe oversaw Glen Grant’s conquest of the Italian market, where it was distributed by the Giovinetti family. ‘Armando Giovinetti came over and bought a few cases, and stuck them in the boot of his car, but Hugh spent a lot of time in Italy,’ says Malcolm.

‘We always knew if Hugh had had a good trip or a bad trip. He made a point when he came in in the morning of walking straight through the tun room and the mash house… If it was a very good trip, he’d stand and chat to you; if it wasn’t so good, he’d walk straight on through.’

Malcolm adds: ‘You knew exactly where you stood with him – he was very transparent and didn’t bend back and forth. The more he sold, the more we had to produce; we worked longer hours and the men made more money, so he was basically our hero.’

Glen Grant days: Hugh Mitcalfe (far right) with Douglas Mackessack (far left), their respective wives and Armando Giovinetti

Mitcalfe left Glen Grant when it was sold to Canadian group Seagram in 1978, moving a few miles south to become the first marketing director at Macallan.

Macallan was then a blender’s malt with a good reputation on Speyside, but little renown beyond its borders. Brothers Allan and Peter Shiach set out to change that, laying down stocks and, as they reached maturity, assembling a small team under Phillips and Mitcalfe to build Macallan’s reputation.

‘Hugh arrived, and I remember that he found us so backward,’ recalls Phillips. ‘We had no telex, for example, and he went on and on and on about this until we got one. But the only place we had for it was in the ante-room of the gents toilet, so the girls from the office had to go in there to send Hugh’s telexes for him.’

He continues: ‘When he came, Hugh realised that Macallan knew nothing – less than nothing – about marketing. He knew we had a good product that was pretty well-known in Speyside, and we did a little marketing of the new spirit to the blenders, but actual marketing of Macallan in bottle there was none – and, to be honest, we didn’t know how to do it.’

For Mitcalfe, one of the attractions of Macallan was its inventory. ‘He’d been told on Speyside that Macallan had absolutely wonderful stocks of mature whisky,’ says Phillips. ‘When he came, about 10 days in he said to me: “I’ve heard a rumour that you’ve got some good stocks, Willie. Could I see them, please?” So I gave him a list and he came into my room and said: “Wow.”’

Cox echos this, quoting Mitcalfe’s first marketing report, dated March 1979:

‘We have excellent stocks of very old whiskies available. I do not believe that any of our competitors can match us in this respect and, properly used, this can give us considerable Public Relation advantage.’

Tall tales: Macallan’s 1980s advertising was witty and well-targeted at its audience

Having the liquid was one thing; knowing how to sell it another. ‘Hugh was a marketing genius in his own way, because he never, ever exploited those stocks, he used them for Macallan publicity,’ says Phillips.

‘He came out with a 25-year-old, not to try and get some rich person to make a huge investment; instead, he called it the Anniversary Malt, because he thought that people with a 25-year anniversary might want to buy a bottle.’

Advertising was a vital part of the mix. David Holmes (who died last September) and Nick Salaman of London agency Holmes Knight Ritchie were brought in, placing quirky little ads next to The Times crossword and coming up with a succession of homespun, witty Macallan ‘story’ adverts illustrated with pen-and-ink drawings by illustrator Anna Midda.

‘Allan Shiach gets the credit as the creative ideas man behind these adverts, but a lot of them came from Hugh Mitcalfe,’ says Phillips. ‘He encouraged everyone at the distillery to to think about stories that might work for the adverts.’

Mitcalfe was also the face of The Advocates of the Macallan, communicating with the single malt’s growing fanbase via the pages of the Easter Elchies Digest. ‘He wrote every three months to people, to all the names who joined this [programme], and his letters were just absolutely terrific,’ says Phillips.

There were, however, creative tensions at times. ‘He and I had a lot of tussles,’ Phillips admits. ‘But behind the tussles was a man with a heart for the product, and of course he was talking to me, whose heart was always totally with the product. We had our little battles, but we became a real team.’

Creative force: Macallan’s marketing helped to transform the single malt’s fortunes

Mitcalfe’s involvement with Macallan ended – as it had done in the case of Glen Grant – in disappointment and a takeover, this time by Highland Distillers in 1996. ‘He was really upset,’ recalls Phillips. ‘He thought that Allan Shiach had sold us out, but the takeover came as a shock to Allan too… He and I were very quickly told we weren’t going to stay.’

Phillips and Mitcalfe, who sometimes travelled together in the US to promote Macallan, were in some ways an odd couple. ‘Hugh was not an aristocrat – that’s not the right word – but he was of that ilk,’ says Phillips. ‘He was public school, whereas I was not – and it showed. I was more of a people man than he was; but he was a gentleman.

‘Hugh was better than I was intellectually – my superior, I think; and, from a marketing point of view, very clearly my superior, and so I had to respect what he wanted to do.

‘Despite our tussles, I always had a high regard for Hugh Mitcalfe. In my life, I count him as one of my real friends, even though we hardly spoke after we left the company.’

Cox adds of Mitcalfe: ‘Of patrician demeanour, together with Allan Shiach and Willie Phillips, he helped develop a personality for The Macallan that is with us to this day.

‘Like them, he didn’t just work for The Macallan; he lived it.’