During its heyday, Milroy’s of Soho was, to many people, ‘the’ whisky shop. Run by brothers Jack and Wallace Milroy, it was a pioneer of single malt, and numbered Michael Caine and Harold Wilson among its many customers. Richard Woodard reports.

On 9 November 1964, a small off-licence called the Soho Wine Market began trading at 3 Greek Street, London W1. Those attending the opening were invited ‘…to sample interesting and unusual wines’, including canned Beaujolais and Macedonian reds. Of whisky there was no mention, but this store – later better known as Milroy’s of Soho – was to become perhaps the most influential whisky retailer in the world, thanks to the efforts of the charismatic Milroy brothers, Jack and Wallace.

When Jack Milroy opened the shop, it stocked a decent selection of blended Scotch, but only four single malts – Glenfiddich, Glen Grant, Tomatin and The Glenlivet. Then, when Wallace Milroy joined the business five years later, everything changed.

The number of malts soon grew to 25, then to more than 150; by 1993, when Jack sold the business, Milroy’s stocked nearly 600 single malts, and the shop’s fame was global. Japanese whisky lovers in London on business would hurry straight from the airport to Greek Street, clutching a formidable shopping list running into the thousands of pounds.

New venture: In the early years of the shop, wine and Champagne were to the fore

The Milroy brothers grew up in Dumfries, where their parents took over the Woolpack Inn in 1948. Aged 14, Jack was, as he recalls today, ‘bored stiff’ by schoolwork at Dumfries Academy. Much better to earn £7 a week as a pot boy in the family pub, mopping the floor every night and laying down fresh sawdust.

A more romantic story would see the Milroy boys nurturing a love for Speyside and Islay as they collected the glasses, but not so: these were the years of post-war austerity. ‘We never bothered with single malts,’ Jack says. ‘Abbot’s Choice was the famous blend, and that was the house brand. But we were all on quota after the war, so there was Danish whisky as well. That was real firewater, I can tell you.’

Soon Jack was a roving relief manager for local pubs, until National Service took him to RAF Brampton in Cambridgeshire. ‘The pubs in England were so different,’ he says. ‘I got the flavour for better standards – it wasn’t good enough for me to go back and be a Dumfries publican.’

Following a business course in Hull and an off-licence diploma at Luton Technical College, Jack got a job managing the Trump’s chain of wine shops in Devon, then moved to London, running a wine store in South Kensington, before being appointed manager of Kettner’s in Soho, billed as ‘the world’s finest wine shop’.

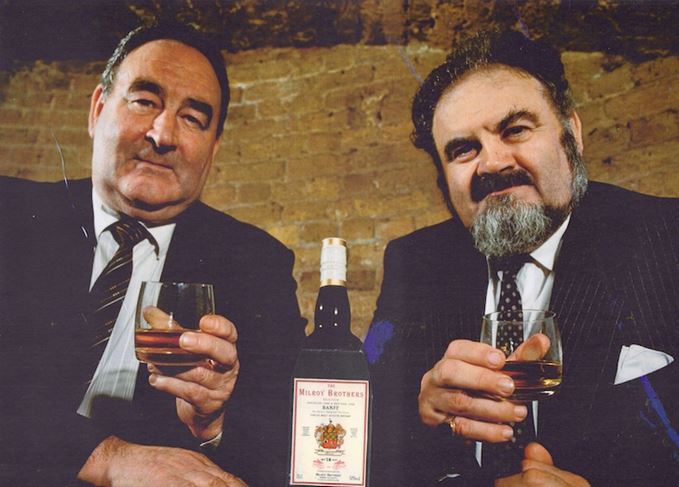

Legendary hospitality: Wallace (left) and Jack were generous hosts in their ‘clan room’

At this stage, whisky barely featured. ‘There was three or four malt whiskies on the list – it was all blends,’ says Jack. ‘Plenty of White Horse, Dimple and Haig. It wasn’t the in thing, you see.’

The two catalysts for change were the opening of the Soho Wine Market, funded by £500 each from Jack’s parents and Wallace, and Wallace’s return to the UK in 1969 after 17 years as a mining engineer and minerals prospector in Africa.

‘He wasn’t sure what to do, but in the meantime I had my eye on another shop in Beak Street,’ says Jack. ‘I said to Wallace: “Look, come and have a go.” He was never too interested in Sauvignon Blanc or Chardonnay – he was more interested in the whisky side.’

Wallace took over the second shop – The Ship Wine Company – and set about trying to expand the whisky selection. He knew that businesses like the Distillers Company Ltd (DCL) bottled single malts for the directors’ dining room, but getting them to admit this – let alone part with any of it – was no easy task.

Number 10: A young Jack Milroy delivers whisky to Prime Minister Harold Wilson

The solution? If the companies wanted Wallace to continue selling their blends, they would have to throw in some single malts as well. Suddenly the barriers fell away.

‘Well, that was Wallace applying his pressure,’ says Jack with a grin. ‘He got very pally with them, and he was a whisky drinker. I think they often tried to drink him under the table but, when it didn’t happen, he got a lot of respect.’

If stocking the right products was important, knowing the right people was vital. At a time when the pubs shut during the afternoon, word soon spread of Milroy’s upstairs ‘clan room’, where the brothers gave generous ‘samples’ of whisky and Champagne. Many, including Brian Barnett of Augustus Barnett, and Ronnie Emmanuel of Wheelers restaurants, became great friends and valued customers for wine and whisky alike.

The brothers’ success – not to mention their famed hospitality – also attracted the great and good of Fleet Street, including editors Arthur Britten (Daily Mail) and John Junor (Sunday Express). ‘We got a lot of good press,’ acknowledges Jack. ‘All sorts of people would come and do an interview, knowing damn fine they’d get a good booze-up when they finished.’

Nosing glasses: When Wallace (left) returned to the UK, he transformed Milroy’s whisky selection

Meanwhile, the proximity of The Gay Hussar restaurant, a regular haunt for politicians, helped cement connections with Westminster. When Harold Wilson was Prime Minister, Jack made regular deliveries of Champagne and whisky to 10 Downing Street.

One day, Michael Druitt, director of Bollinger Champagne, brought his next-door neighbour to see Jack at Milroy’s – an up-and-coming actor called Michael Caine. As a self-confessed ‘nouveau riche’, Caine wanted to build up a wine collection, so the three had what Jack describes as ‘a good lunch’.

‘He wasn’t too impressed at first,’ Jack recalls. ‘Then we got up to Romanée-Conti, which was then £30 a bottle. “John, this is good,” he said. “My wife Shakira would love this. She’s a muslim, but she’d drop her veil for this.” Lunch concluded with Caine spending ‘about £8,000-9,000’ on wine.

Another regular customer was the Crown Prince of a certain Middle Eastern country. Returning to Soho in 2010 as King, he was disappointed to find Milroy’s sold on and neither brother in attendance. But he tracked them down and invited Wallace, Jack, Wallace’s son Craig and Doug McIvor (ex-Milroy’s manager and now at Berry Bros & Rudd) on an all-expenses-paid trip to see the sights of his country.

Decent measure: But Jack Milroy was always more of a wine than whisky drinker

Some of the business deals were as memorable as the anecdotes. Perhaps the most famous began with a visit by the Milroys to Speyside as guests of Peter Grant Gordon in early 1988.

‘We were walking around Balvenie and Wallace, who was very nosy, was looking around,’ Jack remembers. ‘In one corner, there was these four casks with cobwebs on them, and he said: “What’s that?” And Peter said: “Oh, that’s Balvenie 50-year-old.”

‘“That’s interesting,” says Wallace. “Could we have some of that? Could we buy those four casks?” Peter said: “I don’t see why not. Work out a price.”’

The brothers bought 360 bottles at £150 each. By this time, as well as writing the hugely popular Malt Whisky Almanac, Wallace was in demand to host tastings in the Far East; and so the brothers took the Balvenie to Japan for a 30-day lecture tour, selling it on to their local clients at £360 a bottle. By the time the whisky reached its final customer, the price was £1,000.

Four Macallan American oak hogsheads filled in 1949 and later disowned by the distillery were acquired for less than £8,000, then sold to a Japanese client for more than £100,000 during breakfast at Claridge’s; in the course of another dinner at The Cliveden House Hotel, Jack snagged a deal to sell a collection of fine wines, some dating back to 1896, for £1.4m.

‘Fire sale’: Jack was forced into selling Milroy’s for a knock-down price in 1993

Jack’s first car at the age of 33 was a Bentley S2. A selection of Bentleys and Rolls-Royces followed, including a white Silver Shadow funded by the sale of 5,000 cases of Canard-Duchêne Champagne to Augustus Barnett.

Milroy’s was sold in 1993 as Jack went through a messy divorce from his second wife and legal disputes costing tens of thousands of pounds. ‘I had a big overdraft to take care of,’ he says ruefully.

‘I got rid of the business, but I carried on running Milroy’s for the new owner for a couple of years. A fire sale, I think someone called it.’ A plan to sell the business back to Jack after a couple of years never materialised. ‘It wasn’t the same after that,’ he says.

Both brothers remained in whisky – wholesaling, consulting, Wallace hosting lectures and tastings, Jack bottling whiskies under the ‘John Milroy’ name, latterly with Berry Bros & Rudd. Meanwhile, Milroy’s has passed through several hands, including La Réserve and Mark Reynier, who later led the revival of Bruichladdich, and – since 2014 – Martyn Simpson.

Jack today: Pictured with a Berry Bros John Milroy single malt, Jack now lives in Suffolk

Wallace died in 2016, while Jack lives on the Suffolk coast with Mary, his first wife, whom he later remarried. Now in his mid-80s, he doesn’t drink whisky any more – he was always more of a wine man anyway – but has a scrapbook stuffed with the memories of a remarkable era: the deals done over long, long lunches, the gold Rolls-Royces, the legendary clan room ‘sampling’ sessions.

And yet, when the Soho Wine Market opened in 1964, it was just Jack, working 12-hour shifts on his own, fortified by regular deliveries of soup and sandwiches from Mary, making his way and building the business.

‘I remember we threw this party,’ he says with a smile. ‘We must have had about 100 people milling around on the three floors, a bagpiper outside. It was Burns Night, I think, the whisky was flowing and we were in the kitchen, all dressed in tartan, where Wallace’s wife was cooking a big haggis.

‘We had the best of it, I think. We were a great bunch, it really was crazy days and it just kept on going. We started something and others followed. We started something and it just took off.’