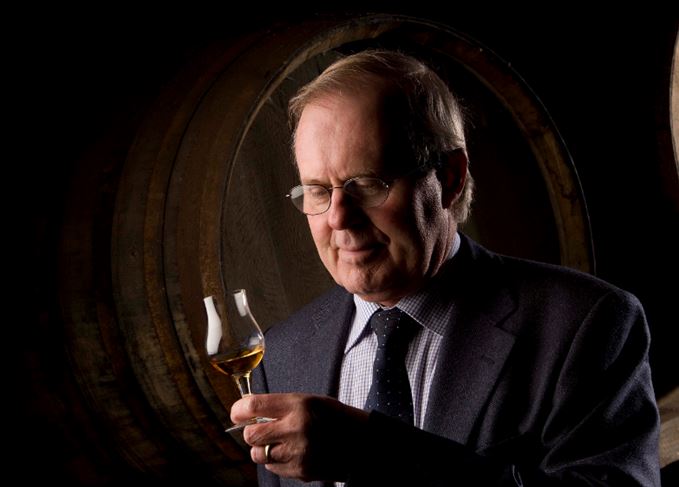

From his humble beginnings as a whisky stocks clerk at William Grant & Sons to his long tenure as Balvenie malt master, David Stewart can look back on a 55-year career, including his exploration of double cask maturation during the 1980s and 1990s. He talks to Richard Woodard about his life’s work and recalls some of the fine (and not-so-fine) finishes created along the way.

‘Good appearance. Appears to be the solid type. Would do.’

The year is 1962, and a 17-year-old David Charles Stewart is being interviewed for a job as a whisky stocks clerk at William Grant & Sons. And, while the notes made in that interview may not be the most laudatory assessment of a prospective employee, they somehow fit the man himself – steadfastly humble and modest, despite the many highlights of a remarkable 55-year career that culminated in the award of an MBE last year.

‘I think it was the chief accountant who interviewed me first of all,’ Stewart recalls. ‘I didn’t start off thinking I would ever become a blender. I just started off as a clerk in the whisky stocks team.’

After two years counting casks, Stewart began to become acquainted with their contents. ‘I was lucky in that my boss [Hamish Robertson] was the master blender. Within a couple of years of me working, he started to bring me into the sample room.

‘I just started to nose the whiskies that were coming through. There weren’t that many in those days, but Girvan distillery had just opened in 1964. We had Glenfiddich and Balvenie distilleries; there was [blended Scotch] Grant’s Standfast.

‘Then Glenfiddich started [as a single malt] in 1964. Gradually I was seeing more and learning more and more from [Hamish], and then he left in 1974. I was just left to get on with running the place after 10 years with the whisky.’

Early days: Stewart was present for the ‘dawn’ of single malts during the 1960s

We’ll move onto what was involved in ‘getting on with running the place’ in a moment. But first, consider the timing of Stewart’s entry into Scotch whisky: the birth of Glenfiddich as a single malt and, with it, the creation of a new commercial category at a time when blends were all-powerful. While his initial involvement with it was minimal, the seismic forces which Glenfiddich set in motion were to shape his career.

Stewart acknowledges the significance of this new era of single malt, but plays it down in characteristic fashion. ‘Yes, the [Grant] family took a big risk in bottling Glenfiddich at the start,’ he says. ‘But in the big scheme of things, single malt is still pretty small. I mean, it’s 15% of industry sales – we still rely on blended whiskies like Johnnie Walker, J&B and Grant’s.’

Nonetheless, the journey of single malt – reflecting and punctuating Stewart’s own career – has been long and eventful since that first consignment of Glenfiddich headed south in 1964. It’s a development encapsulated by the evolution of Balvenie, the Speyside single malt for which Stewart remains responsible in his semi-retirement (Brian Kinsman took over his broader company duties in 2009).

‘When Glenfiddich was launched, it was 10 years before Balvenie – Glenfiddich was 1963, 1964, I think,’ recalls Stewart. ‘So not that I was terribly involved at that stage, but I knew about it, I saw samples coming into the sample room.

‘I think it was the family again who, 10 years later, thought: “Well, we’ve got this great whisky at Balvenie.” With Glenfiddich, the single malt market started opening up. Glenfiddich probably had almost 10 years with very little competition.

Revolutionary move: Stewart’s development of double maturation helped shape modern single malts

‘It wasn’t until the 1970s when Macallan came along, The Glenlivet, Glenmorangie and others. At that stage we thought: “Well, let’s bottle Balvenie.” We put it into a triangular bottle because that’s what we were used to very much at Glenfiddich. In 1973, we launched it at eight years old – Glenfiddich was eight as well and generally quite a lot of single malts that were around at that time were eight. It wasn’t a problem.’

How does he remember that whisky? ‘You still see the odd bottle. I tasted it at The Craigellachie Hotel just last week – they’ve got a bottle there. It was very nice, to be fair. It would be from maybe more European oak then than now, because it would be back to the 1960s for the whisky that was in that bottle. So it was quite rich-tasting, was the eight.’

Evolution followed: a move to a long-necked, Cognac-style bottle, a shift to a 10-year-old age statement. Then, in 1993, came a launch that was, in the man’s own assessment, the highlight of Stewart’s career: Balvenie DoubleWood 12 Years Old.

‘That’s the one that I’m probably most proud of, just because that’s what put Balvenie on the map, and that’s really when Balvenie sales started to become what they are today,’ Stewart says.

DoubleWood’s DNA – aged in American oak, then ‘finished’ in Sherry wood – can be traced back a decade to the early 1980s and Stewart’s pioneering work on extra maturation. What is routine and commonplace in whisky today was then revolutionary – but, perhaps even more remarkably, nobody talked about it.

‘No, it wasn’t marketed as a “finish” then, it was just we wanted to create something a bit different [Balvenie Classic] from the Founder’s Reserve,’ admits Stewart. ‘What would happen if we recasked whisky from American oak to European oak? That produced the Classic and the Classic variants.

‘We were delighted because Sherry wood does add richness, spiciness and complexity and colour – and just a bit more flavour to the whisky. We knew that something was going to happen.’

Spirit clash: Experiments with spirit finishes, such as Cognac and Armagnac, did not work

For all DoubleWood’s success – next year marks its 25th anniversary – it’s still sometimes misunderstood, Stewart adds. ‘People think that a lot of the flavour in the DoubleWood is coming from the Sherry, which it’s not really – it’s coming from the wood, because the wood is only two years old.

‘It’s a two-year-old, brand-new, European oak cask that we use every time for DoubleWood. So a lot of that spiciness is wood spiciness and malt spiciness that gets into the whisky, whereas if you look at Madeira and Port [finishes], most of the flavour there is the Madeira, the Port, because the casks are much older.’

DoubleWood, Portwood, Madeira Cask, Caribbean Cask – a pioneering production line of Balvenie ‘finishes’ that was born in that fertile period of experimentation. But if the malt’s history is written by the winners, the losers can be just as educational in their own way.

‘We tried quite a number,’ Stewart recalls. ‘We tried other spirits like brandy, for example, and Cognac and Armagnac, and they didn’t work for us. The two spirits just kind of fought with each other and there was a clash between the two.

‘We tried a number of wines – maybe not always the right wines, and maybe they weren’t always sweet enough. The ones we did try were Californian wines – white and red – because they were easy to get, but they didn’t really work for us. They didn’t really change the whisky all that much.’

Blended away, a cask at a time, into William Grant’s older blends, only the chastening memory of these failed experiments remains. ‘That’s probably the beauty of our company,’ says Stewart. ‘If it doesn’t work, then we’re not forced to bottle it.’

If there’s a general conclusion to be drawn from this feverish period of innovation, it’s that a relatively rich malt such as Balvenie needs something extra – sweetness, fortification – in a wine cask. ‘That could be,’ Stewart agrees. ‘We’ve got one or two in our warehouse – a Sauternes or Barsac, or a Marsala – to try and see if they might give us something for the future.’

Peat week: Stewart has overseen the release of a new smoky Balvenie bottling

From past and future, back to the present. The reason we’re talking in the first place is the launch of Balvenie Peat Week, the second of two peated variants launched by the distillery this year.

First discussed as long ago as 2001, the whisky is the result of an annual week of peated runs through the distillery, beginning in 2002. ‘We use peat in our bottlings at Balvenie anyway, but it doesn’t show through particularly in any of the expressions,’ says Stewart.

‘At first, we didn’t really know what we were going to do with it, we just thought it was good to have it… We’ve not used it all, we’ve held stock back, so we might decide to do a 17, or a 21. And I know someone was joking about having a 50-year-old…’

But anyone expecting a Speyside take on a super-peated Islay malt will be confounded. ‘It was peated to 30ppm [phenol parts per million], but that’s the barley itself, and when it translates into the bottle, it’s only 5-6ppm,’ points out Stewart.

‘We didn’t want to dominate the Balvenie style. We wanted it still to be very much Balvenie, but to have this little bit of smokiness. And it’s Speyside peat, it’s from Aberdeenshire, so it’s quite different from the Islay peat. That’s more kind of medicinal, but this is a softer kind of smokiness – more in the background.’

Stewart also resists suggestions that Peat Week is some kind of gimmick that risks compromising distillery character. ‘Balvenie has been peated – we used peated malt back in the 1930s and 1940s and I’ve seen some of that whisky in my time with the company,’ he points out. ‘The style would be quite different moving back – it would be quite smoky.’

What’s in the glass reflects Stewart’s carefully chosen words and, in a deeper sense, the character of the man as well. Peat not as a dominant force, but as a seasoning, happy to play an accompanying role and to allow the character of the distillate to shine through.

Substance over style, continuity of character above short-term show. Every master blender has his or her own unique way of doing things but, in the end, it’s the whisky they produce that creates their legacy, and that speaks most loudly to the world.