Whisky from closed distilleries is a precious and dwindling resource, says Angus MacRaild, so treat them respect: don’t ‘lose’ them in a blend, but let them live on as single malts in their own right.

At The Whisky Show in October, I was tasting the recent Diageo Special Releases Convalmore. It’s a beautiful whisky, almost Clynelish-esque in its waxiness – it lingers long in the mind.

I was struck to hear that there had been a serious tussle between the Special Releases team and the blenders over what purpose those stocks of Convalmore were to serve. An older, waxy-style malt had been desired by the blenders for a high-end blend – and those casks of Convalmore fit the bill.

That this was ever in consideration seems to me to cut right to the heart of the division between those who make whisky and those who drink it.

We are now at a point where it’s fairly obvious that stocks from closed distilleries are scarce. Many are spent; those that aren’t dwindle low. Almost all the distilleries that closed in the 1980s were shut, not only because they were deemed surplus to requirements at the time, but because they were usually distilleries which had not had serious money spent on upgrading them in the preceding decade.

Glenlochy, Glenugie, Brora, Coleburn, Convalmore – it made more sense at the time to close these sorts of distilleries than to shut the likes of Glendullan, which had recently undergone serious and expensive expansion.

The upshot was that the makes from most of the distilleries that shut were often characterful – examples of an older style of whisky production which, while perhaps not appreciated or considered remarkable at the time, would come to be cherished by drinkers in the decades that followed, both at younger and older ages.

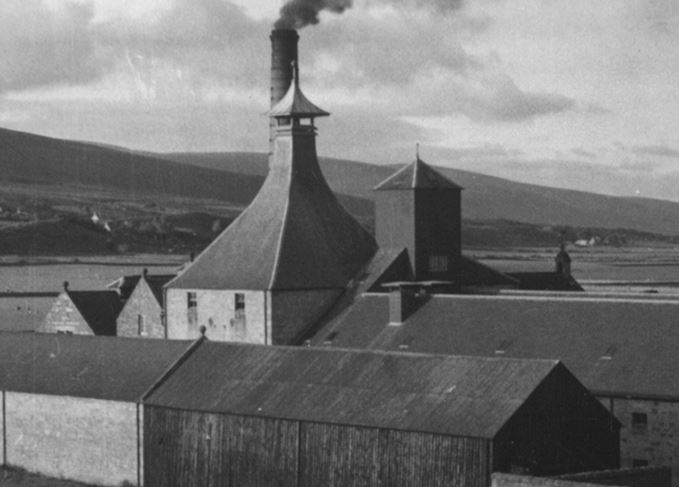

Beautiful whisky: But Convalmore’s dwindling stocks are also sought-after by blenders

Very few distilleries now produce this waxy and textural style of malt. The planned production style at the re-opening Brora speaks volumes about Diageo’s awareness of the desire for this character among whisky enthusiasts.

I would argue that the remnant stocks from these closed distilleries are precious. They are the product of a different era: the sum of different production methods, different ingredients, a different culture, and – most importantly – different people.

To blend such stocks away – whether without fanfare into the nameless graveyards of some older, high-end blends, or as the lauded base for something like the new Johnnie Walker Blue Label Ghost & Rare – smacks of disrespect to these whiskies.

This is clearly not a position shared by the blenders at Diageo, and other companies with stocks from closed distilleries. As Diageo has often posited, it is a blending company. Its primary purpose is not to release myriad single malts, but to create varied stocks from which to compose a broad range of blended whisky products.

This is where the division lies between the producers and the single malt enthusiasts. To me, a cask of Brora is liquid history and deserves to be preserved in singularity. To a blender like Jim Beveridge, it is a vital component in a bigger picture. To both of us it is beautiful and precious, but our perspectives arrive from quite different directions.

The blenders would argue that my perspective is that of the single malt snob, dismissing blends as inferior. I don’t deny I generally favour malts over blends, but if a certain flavour profile is needed for a blend, then there are other options.

Stocks from extant distilleries such as Clynelish, Caol Ila or Glen Ord can perform a similar function to the character of these lost makes. Is the art of blending not in the creativity of recreating a flavour profile, not always with the same ingredients?

Spectral whisky: Johnnie Walker Ghost & Rare is built on the closed (but soon to reopen) Brora distillery

This new Ghost & Rare bottling is being sold off the back of the name Brora – that is the reason for that whisky’s inclusion. However, it doesn’t follow that to create that flavour profile it is essential to use Brora in the blend.

Of course not all casks of closed distilleries are ‘good’ either. I appreciate there may be exceptions where individual casks will be markedly inferior. Should these be put into high-end blends at all, though? The line about duff casks usually goes that they are squirreled away into big-batch blends – not put into high-end bottlings such as the Ghost & Rare.

I would argue that, while there may be some substandard casks, the quantities of these stocks are no longer so vast that they shouldn’t be carefully judged on a cask-by-cask basis and, wherever possible, bottled as single malt. It is fundamentally about respecting what have become – by accident of history – important, relevant and finite stocks of whisky.

As a lover of whisky, given the option, I would always prefer to see a cask, or casks, of a malt such as St Magdalene bottled, rather than blended – no matter how good the resulting blend might be. There is pleasure to be had in whisky from closed distilleries that goes beyond initial olfactory appreciation. The knowledge of what you are drinking is part of the experience.

However, I don’t believe the same can be said of grain whisky from closed distilleries. The nature of grain as a neutral alcohol, with flavour derived almost entirely from wood, renders it a different beast from these lost single malts.

The whisky from closed single malt distilleries derives its importance from distinction of character and identity. Its flavour is information about the process and culture of its creation; something also true of grain whisky, but apparent in a far more minimalistic, streamlined and, dare I say it, uniform way.

Malts over blends: MacRaild would rather see a ‘lost’ malt like St Magdalene bottled on its own

This is not to ‘diss’ grain whisky, or to deny its commercial necessity to the whisky industry. But its inherently consistent nature means it need not be approached from the philosophical perspective with which we consider how to treat malt whisky.

For the people who made these lost distillates, it would have been very much ‘a job’. Contrary to popular marketing mythology, most distillery workers did not consider themselves artists or lofty craftsmen.

In the economically stagnant decades of mid-20th century Scotland, there were more important things than whisky to concern yourself with, and jobs were precious. That out of this some terrific single malts were produced makes these remnant stocks all the more important and remarkable today.

They remain historically relevant and beautiful by accident – relics of an industry and culture long since changed. This is something that deserves preservation, attention and respect.

Give me a cask of Convalmore – even one slightly too tired, slightly too old or slightly too weak. I’ll still take joy in the story that whisky tells me when I drink it. I’ll admire it because of its fragility, not in spite of it.

I’ll think on the time it’s spent getting to me, and all that’s changed in between. I’ll think on the people who made it, how their lives and localities differed from mine, and how bewildered they’d be at the price I no doubt paid to drink their whisky all these years later.

And I’ll be glad it’s in my glass, and not forever lost in a crowded blend.