In the third and final instalment on the rules of Scotch whisky making, Dave Broom turns his attention to the complex matter of labelling. Here, he covers the differentiation between single malts, single grains and blends, the geographical division between the Highlands and Lowlands, and the use of distillery names on bottlings.

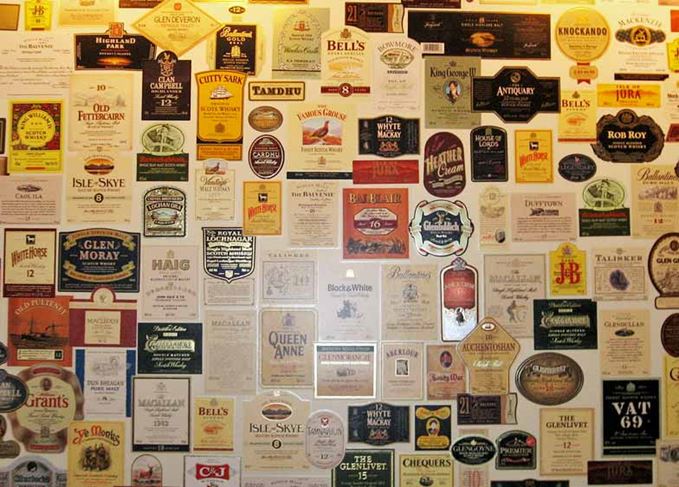

Did you think we’d finished after we looked at casks? Think again. The Scotch whisky regulations stretch on for many, many more pages. We’ll draw this examination to a close with a shufti at labelling and definitions. Don’t turn away. It might not directly impact on flavour (which has been the theme thus far), but there are some important nuggets within its clauses.

What have we learned so far? That the Scotch Whisky Act both protects whisky and allows distillers sufficient flexibility to create something which is specific to that site – and also permits innovation to take place. That, after all, is what makes Scotch whisky such an endlessly fascinating – nay, obsessive – subject.

In fact, the opening lines of the section dealing with what that liquid can (or cannot) be called repeat that:

‘(2) In these Regulations –

“Single Malt Scotch Whisky” means a Scotch Whisky that has been distilled in one or more batches –

(a) At a single distillery;

(b) From water and malted barley without the addition of any other cereals; and

(c) In pot stills;’

You know, just in case you had forgotten.

The nature of how a distillery’s name can be used is also protected.

‘The name of a distillery mentioned… must not be used as a brand name, or as part of a brand name of a Scotch Whisky, or be used in a similar fashion in terms of its positioning or prominence, unless the whisky has been wholly distilled at that distillery.’

It continues on in this vein for another four paragraphs which, to summarise, say you can’t use the name of a distillery to promote another product, inferring it comes from that distillery (when it doesn’t), or suggest the reverse – that the product was made at another distillery, or by someone else other than the people who produced it, (ie there’s no piggybacking on someone else’s fame).

In practical terms, this means you can’t have a single malt bearing the name of a distillery and also have a blend with the same name, or have a blended malt using the name of a single distillery.

Even though Eden Mill fulminated about this recently when they tried the first option, if you had been around during the Cardhu fiasco (when an attempt was made to use the name of a single malt distillery for a blended malt product (the second option)), you’ll know that these restrictions make perfect sense.

(It would be interesting to see what might happen if Eden Mill took the Bushmills approach, calling the malt Eden Mill, and the blend ‘Black Eden’ or some such. Just sayin’...).

The label can also say in which of the regions or ‘protected localities’ the distillery is located. They are:

‘(a) “Campbeltown”, comprising the South Kintyre ward of the Argyll and Bute Council as that ward is constituted in the Argyll and Bute (Electoral Arrangements) Order 2006(a); and

(b) “Islay”, comprising the Isle of Islay in Argyll.’

Pretty self-explanatory, though defining a region by electoral boundaries rather than geological features is something we’ll pick up on in a second.

‘(6) The protected regions are:

(a) “Highland”, comprising that part of Scotland that is north of the line dividing the Highland region from the Lowland region;

(b) “Lowland”, comprising that part of Scotland that is south of the line dividing the Highland region from the Lowland region;’

Scotch whisky regions: An old taxation line separates the Highlands from the Lowlands

So what is the line? I was brought up understanding the Highlands and the Lowlands were divided by the Highland Boundary Fault, which runs in a long diagonal from Arran to Stonehaven. In geological terms, it is the abrupt (and often spectacular) division between the hard Dalradian rocks of the Highlands and the eroded sedimentary rocks of the central Lowlands.

The Scotch Whisky Act boundary:

‘…means the line beginning at the North Channel and running along the southern foreshore of the Firth of Clyde to Greenock, and from there to Cardross Station, then eastwards in a straight line to the summit of Earl’s Seat in the Campsie Fells, and then eastwards in a straight line to the Wallace Monument, and from there eastwards along the line of the B998 and A91 roads until the A91 meets the M90 road at Milnathort, and then along the M90 northwards until the Bridge of Earn, and then along the River Earn until its confluence with the River Tay, and then along the southern foreshore of that river and the Firth of Tay until it comes to the North Sea.’

This is actually one of the old taxation lines which were in operation prior to the 1823 Excise Act. It also places all the islands (bar Islay) within the Highland designation.

Does this affect any distilleries? Actually, yes. In a quick calculation, if you take the boundary fault to be the border, then Loch Lomond, Deanston, Tullibardine, Glencadam and Fettercairn would all become Lowland, with Strathearn and Glenturret on the cusp.

It also means that in both definitions, the original distillery on Arran at Lochranza is in the Highlands, while the firm’s new build at Lagg is in the Lowlands. (Now there’s a marketing opportunity).

I suppose that’s the point. The regional approach is more to do with marketing than terroir. It demonstrates that Scotch comes from all parts of the country. It is unlikely, however, that anyone will agree that all the whiskies made in the Highlands, no matter how you define the region, share a singular identifiable character with the other members of the grouping, which is then different to all the other regions.

You might think that Speyside would cover the watershed of the Spey, but that area comprises:

‘(i) The wards of Buckie, Elgin City North, Elgin City South, Fochabers Lhanbryde, Forres, Heldon and Laich, Keith and Cullen and Speyside Glenlivet of the Moray Council as those wards are constituted in the Moray (Electoral Arrangements) Order 2006(b); and

(ii) The Badenoch and Strathspey ward of the Highland Council as that ward is constituted in the Highland (Electoral Arrangements) Order 2006(c).’

This does make you wonder what will happen when constituency boundaries change.

Also, you don’t have to declare that you are part of the region. Technically, Dalwhinnie is in Speyside, but calls itself Highland. So do Glenfarclas and Macallan. Regions are a guide and a useful marketing tool, not a legally binding appellation contrôlée.

Highland or Lowland?: Glenturret practically straddles the Highland Boundary divide

Any influence of terroir is, I believe, more site-specific than regional, so while useful, treat regions with care. They do not automatically define flavour. You could argue that a whisky list divided by region makes less sense to a consumer than one divided by flavour.

What’s next?

‘“Single Grain Scotch Whisky” means a Scotch Whisky that has been distilled at a single distillery;’

In other words, it’s the same principle as single malt. This does raise the issue of what you should call a whisky created from a mash made from 100% malted barley that’s been run through a column still. Loch Lomond tried (sensibly in my view) for a separate definition for this style – ‘column still malt’ or some such – but the plea was rejected. Malt can only be made in pot stills. Anything else is grain whisky.

‘“Blended Scotch Whisky” means a blend of one or more Single Malt Scotch Whiskies with one or more Single Grain Scotch Whiskies.’

OK, yes, got that. But that’s followed by:

‘“Blended Malt Scotch Whisky” means a blend of two or more Single Malt Scotch Whiskies that have been distilled at more than one distillery;’

And:

‘“Blended Grain Scotch Whisky” means a blend of two or more Single Grain Scotch Whiskies that have been distilled at more than one distillery.’

These last two definitions were introduced in 2009 to stop potential confusion. Prior to this, malt brands made from more than one distillery were known within the trade as vatted malts. This term, however, was never put on the label. Instead, some called themselves ‘pure malts’, but some single malts also used the same term. Others called themselves ‘pure single malts’. There was no doubt that this was confusing. The word ‘pure’ is now banned as a term to be used in labelling, pack, sales, advertising and promotion.

Why blended malt, though? Isn’t it too similar to blended Scotch? Doesn’t it cause an equal amount of confusion? Anecdotal evidence suggests it does. I’d think it easier to have ‘single malt whisky’, and ‘malt whisky’; ‘single grain’ and ‘grain’ – or even vatted, but hey...

No-one will ever agree on every rule. But they should be open to change if that alteration is clearly of beneficial use to the consumer, yet still helps to protect Scotch whisky’s character and good name.

This is the third article in a series on the rules governing Scotch whisky. Additional pieces cover the basics, and distillation and casks.