The advent of Ailsa Bay has shone a light on the issue of innovation and flexibility in distilleries. And yet multifunctional distilleries are far from being a 21st-century phenomenon, as Dave Broom relates.

The sudden arrival of Ailsa Bay – and, let’s face it folks, we didn’t see that one coming – has, rightly, seen the I-word being bandied about. That’s innovation, by the way.

Does Ailsa Bay break new ground? In some ways, yes. Here is a distillery which produces four styles: fruity, meaty, and two peaty expressions.

What is more, it condenses the lightly and heavily peated distillates in copper condensers – giving a fruitier note – and in condensers made of stainless steel – adding meatier elements. That’s two levels of peat and four outcomes. Still with me?

It has also made ‘Irish’ single pot still, and this ‘multi-stream’ approach aligns it more closely with Japanese single malt plants than with most of its Scottish counterparts.

But it’s not, as some have claimed, ‘unique’. Roseisle is multi-stream, and its flexible system encompasses the use of interchangeable stainless steel and copper condensers.

Springbank and Bruichladdich are multi-stream too, and many other distilleries run unpeated and heavily peated.

The other aspect which appears to set Ailsa Bay apart is its location within Grants’ Girvan site. That also is unusual, but it isn’t the sole example. Rather, it is a return to a much older tradition – the multifunctional distillery.

Ailsa Bay: the latest in a long line of multifunctional Scotch whisky distilleries

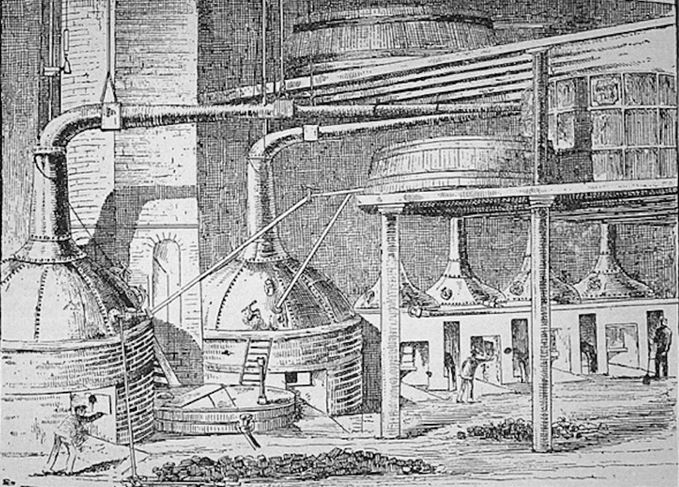

The 19th century saw a large number of distilleries, mainly in the Lowlands, being converted from pot stills to making grain whisky in patent or Coffey stills.

Some, it should be noted, made malt whisky in the new columns – and ‘Irish single pot still’ – showing what we think of as innovative isn’t exactly new, but that’s something else we can chat about at another time. Some, though, made pot still malt and grain on the same site.

Kirkliston made both styles in the late 19th century, as did Paisley’s Saucel site, which operated until 1903. Glasgow’s Dundashill, which was the largest pot still distillery in Scotland at the time, had a column still installed in 1899 which ran for three years.

Its production was absorbed into the equally mighty Port Dundas, which operated five pots and three Coffey stills for a period, before becoming a purely grain plant. Cameronbridge also had two pot stills which ran until the 1920s.

The idea of the multifunctional plant was revived in 1938 at the then new Dumbarton grain plant, which had been built by the Canadian distilling firm Hiram Walker. Flexible distilleries are, after all, a Canadian as well as Japanese speciality. Dumbarton’s Inverleven malt distillery started in 1938, and in 1959 a Lomond still was installed.

Maybe there was something about non-Scottish ownership which saw this as perfectly sensible approach. Joseph Hobbs installed a Coffey still at Ben Nevis in 1955 and started his blending at birth experiments.

The same happened at Lochside, also connected with Hobbs, whose Coffey still was put in place in the late ‘50s, while the Kinclaith single malt plant was built within Strathclyde distillery in 1957-58 when then owner Long John was part of American-owned Seager Evans.

A river runs past it: Strathclyde distillery once contained a single malt plant

The trend continued into the 1960s. The Invergordon grain distillery shared space with the Ben Wyvis single malt plant from 1965 and, in the same year, Inver House’s Glen Flagler plant started up within the Garnheath grain plant.

This would, in time, produce three single malts: unpeated Glen Flagler, low peated Killyloch and the smoky Islebrae. As I said, there’s nothing new under the sun!

The year after – guess what? – William Grant & Sons built a single malt distillery in Girvan and called it Ladyburn.

Why was there this rush? In a word, blends. Scotch was booming in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s as the American market began to kick in. Extra capacity was required and it made financial sense to double up at existing sites, rather than incurring the extra expense of building on a new site.

The lifespan of most of these distilleries was short. Why? In a word, blends, but it wasn’t always as simple as their closure being the result of a downturn in the market. It was as much to do with distillers assessing their overall capacity and adjusting to suit.

While less malt might have been required, grain also needed to be upped. Ladyburn, for example, closed in 1975 when Girvan’s grain side needed to expand. The same happened to Kinclaith, when Strathclyde was expanded, and at Invergordon, where Ben Wyvis closed in 1976.

The opposite was the case at Lochside, whose Coffey still fell silent when the firm was bought in 1973 by Spanish distiller DyC, possibly because it already had sufficient grain capacity. The same went for Ben Nevis, while Glen Flagler stopped in 1985 (the Killyloch and Islebrae pots had been silenced in 1970).

Inverleven bravely waved the flag until 1991, although the Lomond still had ceased production six years earlier. The experiment was over. Or was it?

There was one distillery which quietly continued this approach. One that no-one talked about. Loch Lomond.

It already had pot stills with rectifying plates in their necks, allowing different flavour streams to be produced and, in 1993, two continuous stills were installed to make grain whisky. By the time an additional continuous still was added, which makes grain whisky from a 100% malted barley mash, Loch Lomond was capable of producing eight distillate streams. It was as close as you got to Japan – or Canada – in Scotland.

Why, though, if the experiment appeared to run its course, was Ailsa Bay built? Not just blends, but single malt. The distillery was built to relieve pressure on Grants’ Dufftown stills – particularly Balvenie which was by now an established single malt.

At the same time, Grants’ blends were also growing, and that ‘Balvenie style’ was still required. While purists may tut, it’s a pragmatic solution.

Are we on the cusp of another wave of multifunctional distilleries? There’s long been talk about Starlaw also making malt, while Mossburn will definitely have both grain and malt. Other new builds have mentioned columns as well as pots.

Flexible thinking. It might just catch on.