From illicit beginnings to its status as an archetype of ‘the Speyside style’, the remote Glenlivet valley has played a hugely influential role in shaping the modern world of Scotch whisky. Iain Russell reports.

Glenlivet was once celebrated as much more than ‘just’ the home of a great single malt brand. This scenic valley in rural Banffshire has had an enormous influence on the development and character of the Scotch whisky industry – quite disproportionate to its size and population. And its whiskies have shaped and defined what we think of today as the Speyside ‘style’.

The River Livet is formed by the confluence of two streams high in the foothills of the Grampian mountains. It flows gently for nearly nine miles north through the broad verdant glen to which it gives its name, before emptying in to the River Aven, a tributary of the mighty Spey. Today, the name is pronounced ‘livit’, but it was traditionally called ‘leevit’ by the Gaelic-speaking people who lived there.

The glen was inaccessible by road until the 1820s, and was often cut off from the surrounding countryside by heavy rains and snow. Even now, the spectacular Braes of Glenlivet, at the southern end of the valley, retain a mysterious, Brigadoon-like aura.

William Gordon of Bogfoutain, who farmed at Auchorachan in the 18th century, is the earliest known distiller in Glenlivet. It was recorded that he ‘acquired a considerable fortune, chiefly by his industry as a tenant and by distilling and retail of whisky’. By the time of his death in 1790, many of his neighbours had joined him as whisky-makers, to supplement their incomes from farming.

Smugglers’ dram: Glenlivet whisky was transported in small casks called ‘ankers’ (National Museums of Scotland)

The area’s population was estimated at about 2,000 people in the early 19th century, when there were believed to be up to 200 small stills at work in the glen – none with a permit to do so legally. It was, quite literally, a cottage industry: the women of the house were often responsible for brewing and for tending to the family’s small pot still while the men worked in the fields and pastures.

Its remoteness made it difficult to enforce the Excise laws in the glen. Gangs of smugglers bought and carried the whisky south, usually in small casks, or ankers, slung across the backs of sturdy ponies.

Smuggled ‘Glenlivet’, distilled slowly in pot stills using malted bere or barley, became Scotland’s most sought-after whisky and fetched a higher price than the more fiery products of licensed Lowland distilleries.

Such was its fame that distillers in neighbouring glens began to use the name for their own whisky and, by the early 19th century, ‘Glenlivet’ had become the popular generic name for the Highland pot still ‘style’ – much as Cheddar came to be the name given to a popular type of cheese, and London to a style of gin.

What did this ‘Glenlivet’ whisky taste like? We have no tasting notes in the modern sense, but most contemporary observers wrote of a flavoursome drink – ‘mild as mother’s milk’, in the words of Elizabeth Grant of Rothiemurchus, describing a well-matured Glenlivet.

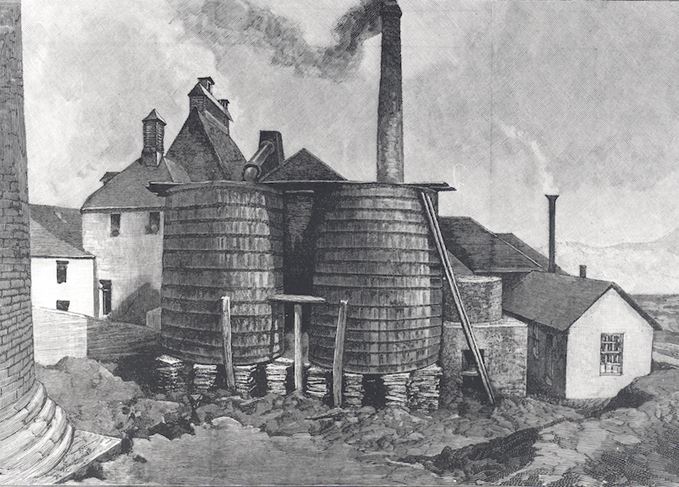

Peat reek: The Glenlivet continued to source peat from Faemussach Moss well into the 20th century (Illustrated London News, 1890)

It was also characterised by a distinctive ‘peat reek’: the glen’s inhabitants relied almost entirely on peat for heating and cooking, but also for drying their malt.

With big profits to be made, Glenlivet smugglers became increasingly bold and reckless, and fought pitched battles with the Excisemen who tried to intercept their convoys en route to Scotland’s towns and cities.

The landowner, the Duke of Gordon, had turned a blind eye to the illicit trade because it enabled tenants to earn cash with which to pay their rents. But growing condemnation of the lawlessness on his estates forced him to take action.

After the passing of the Excise Act in 1823, making it easier for small distillers to operate in the Highlands, the Duke announced that any tenants found distilling illegally in the glen would be prosecuted to the full extent of the Excise laws and, if convicted, evicted from their farms. At the same time, he encouraged people to take out licences to distil, and to pay duty on their spirits.

George Smith, a farmer at Upper Drumin and a grandson of Gordon of Bogfoutain, was one of the new ‘entered’ distillers. Another was Captain William Grant, who revived distilling at Auchorachan.

Modern transport: By about 1924, up-to-date machinery was being used in Glenlivet

Some of their neighbours did not take kindly to these new enterprises, as they knew that licensed distilleries would bring a permanent Excise presence to the glen. Smith had to mount a round-the-clock armed guard at his premises, after he received threats to burn down his buildings. Eventually, however, soldiers were deployed in the area to support the Excise officers in stamping out the illicit trade.

The new Glenlivet distilleries found it difficult to compete with the larger distilleries in the south, and most were forced to close within a decade. George Smith, who was effectively bankrupt in 1826, would have gone the same way.

However, the Duke of Gordon realised the importance of his enterprise to the local economy, both as an employer and as a regular and reliable customer for local barley. He provided Smith with financial assistance and helped him find customers to enable him to carry on.

When the Auchorachan distillery was forced to close in 1854, George Smith was the sole surviving licensed distiller in the glen. He relocated his Glenlivet distillery to his farm at Minmore and, as the demand for single malt from southern whisky blenders soared, his business boomed.

When the popular taste for big, peaty whiskies declined, the distillery simply adapted the traditional Glenlivet style. Accessing supplies of coke through the new Strathspey Railway, it began to produce a less peated whisky with a rich, fat character and a pronounced ‘pineapple’ flavour.

21st-century glen: By 2010, The Glenlivet distillery had expanded significantly

This new style of Glenlivet was very popular with the big Lowland blending houses, and was consciously imitated by the new wave of distilleries opening in Strathspey in the later 19th century.

Smith’s son, John Gordon Smith, subsequently tried to register ‘Glenlivet’ as a trademark, but he and his successors were unable to prevent others using it. The licensed trade, for example, continued to classify whiskies from the Strathspey area as ‘Glenlivets’ until a new name, ‘Speyside’ was invented for the category.

Meanwhile, legal action taken in the 1880s failed to win sole rights to use the name: it didn’t help the Smiths’ cause that their agent named its popular brand ‘Usher’s Old Vatted Glenlivet’, even though it was a blended Scotch, and contained only a very small proportion of whisky from Minmore.

Eventually, the definite article was added to the distillery name, and the brand which the trade had referred to as ‘Smith’s Glenlivet’ became ‘The’ Glenlivet.

Famous for its whisky, Glenlivet was also well-known as the birthplace and training ground of some of the most influential personalities in the Scotch whisky trade. The Grants of Glenfarclas, for example, were originally George Smith’s neighbours.

John Smith of Cragganmore was rumoured to be one of George Smith’s illegitimate children, and James Grant, the son of the distillery manager at Auchorachan, was a key figure in the history of Highland Park.

New arrival: Invergordon’s Tamnavulin distillery was built in the glen in 1966

The whisky wheeler-dealer Jimmy Barclay, Sam Bronfman’s Mr Fix-it in Scotland in the 1930s, and the man who bottled Chivas Regal for Seagram Distillers in the 1950s, was also born in the glen.

And of course there were the Smiths themselves. George and his son John Gordon Smith were followed by George’s grandson, George Smith Grant. As president of the North of Scotland Malt Distillers’ Association, he led the malt whisky distillers in their doomed fight against the big blenders in 1909, in the ‘What is Whisky’ case.

The founder’s great-grandson, Bill Smith Grant, spearheaded the drive to re-establish the market for single malts in the US after Prohibition ended in 1933. He worked tirelessly to establish The Glenlivet there after the war, and it has remained the best-selling single malt in the US ever since.

The Glenlivet’s monopoly of whisky-making in the glen ended in the 1960s. In 1966, Invergordon Distillers built a new distillery at Tamnavulin, primarily to provide single malt for blends. Tamnavulin closed in 1995, two years after the parent company was acquired by Whyte & Mackay, but reopened in 2007.

Braeval was built by Chivas Brothers in 1973 and was originally named Braes of Glenlivet. It was one of the first fully-automated distilleries in the country, but its greatest claim to fame is probably that it was built at 365m above sea level – and as a result competes with Dalwhinnie for the title of the highest distillery in Scotland.